The world of ancient reptiles holds countless mysteries, but none quite as strange as the bizarre creatures that walked, swam, and soared during the Triassic period. This era wasn’t just about the earliest dinosaurs – it was a time when evolution went completely wild, creating animals so unusual that they barely seem real. Picture a reptile with a neck longer than a giraffe’s, or creatures sporting parrot-like beaks instead of teeth. These aren’t fairytales, but the incredible reality of Triassic life.

The Age of Experimentation

The Triassic period began roughly 252 million years ago, emerging from the ashes of Earth’s most devastating extinction event. This event occurred at the end of the Permian, when 85 to 95 percent of marine invertebrate species and 70 percent of terrestrial vertebrate genera died out. It was like starting over with a nearly blank evolutionary slate.

While it’s hard to argue that any geologic period other than the Cretaceous (145-66 million years ago) is the best one, for me, the Triassic (252-201 million years ago) comes in a very close second place. Bordered by two of the Big Five mass extinctions, it was a period of recovery and rapid diversification. Many of the lineages that appeared didn’t make it through the Triassic-Jurassic extinction at the end of the period, so there are many animal groups that are unique to the Triassic, never seen before or since. This wasn’t just recovery – this was nature throwing everything at the wall to see what stuck.

The Hammer-Headed Plant Munchers

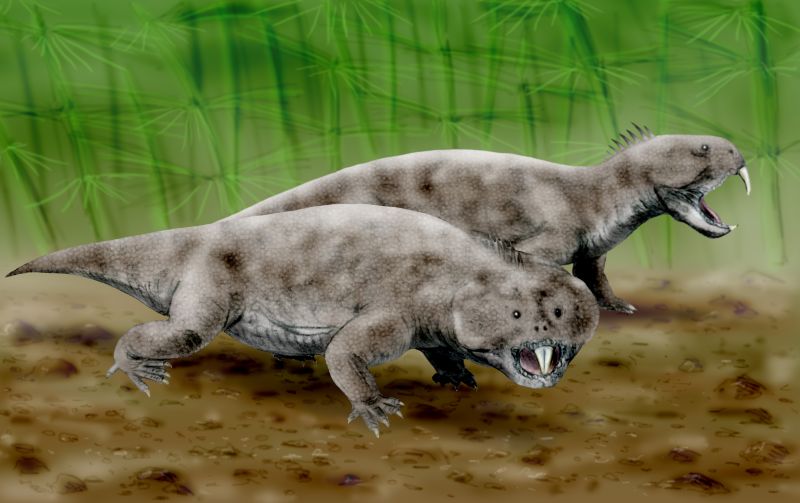

Imagine a reptilian pig with a hammerhead, no visible ears, and a parrot-like beak, and you’ll have a pretty good mental picture of a rhynchosaur. These weren’t your average plant-eaters. Rhynchosaurs dominated the middle Triassic landscape with their bizarre hammer-shaped skulls and parrot beaks that would make any pet store jealous.

They were exceptionally abundant in the middle of the Triassic, as the primary large herbivores in many Carnian-age ecosystems. They sheared plants with premaxillary beaks and plates along the upper jaw with multiple rows of teeth. These creatures had evolved the most unusual tooth arrangement imaginable – many rows of small teeth closely packed together in the upper and lower jaws, like kernels of corn on a cob. Talk about overengineering your dental work!

The Neck That Defied Physics

If you think giraffes have impressive necks, wait until you meet Tanystropheus. It is recognisable by its extremely elongated neck, longer than the torso and tail combined. The neck was composed of 13 vertebrae strengthened by extensive cervical ribs. This wasn’t just long – it was absurdly, impossibly long.

The living animal could reach lengths of about 20 feet, and most of that was neck. The reptile had evolved 13 ludicrously long vertebrae to support its 10-foot neck, longer than its torso and tail together. Particularly telling is the animal’s center of gravity, which would have made walking on land extraordinarily difficult with such a disproportionate neck. Computer modeling of its swimming capabilities suggests Tanystropheus would have been an effective aquatic predator, using its unusual body shape to advantage in shallow marine environments.

Beaked Dinosaur Relatives

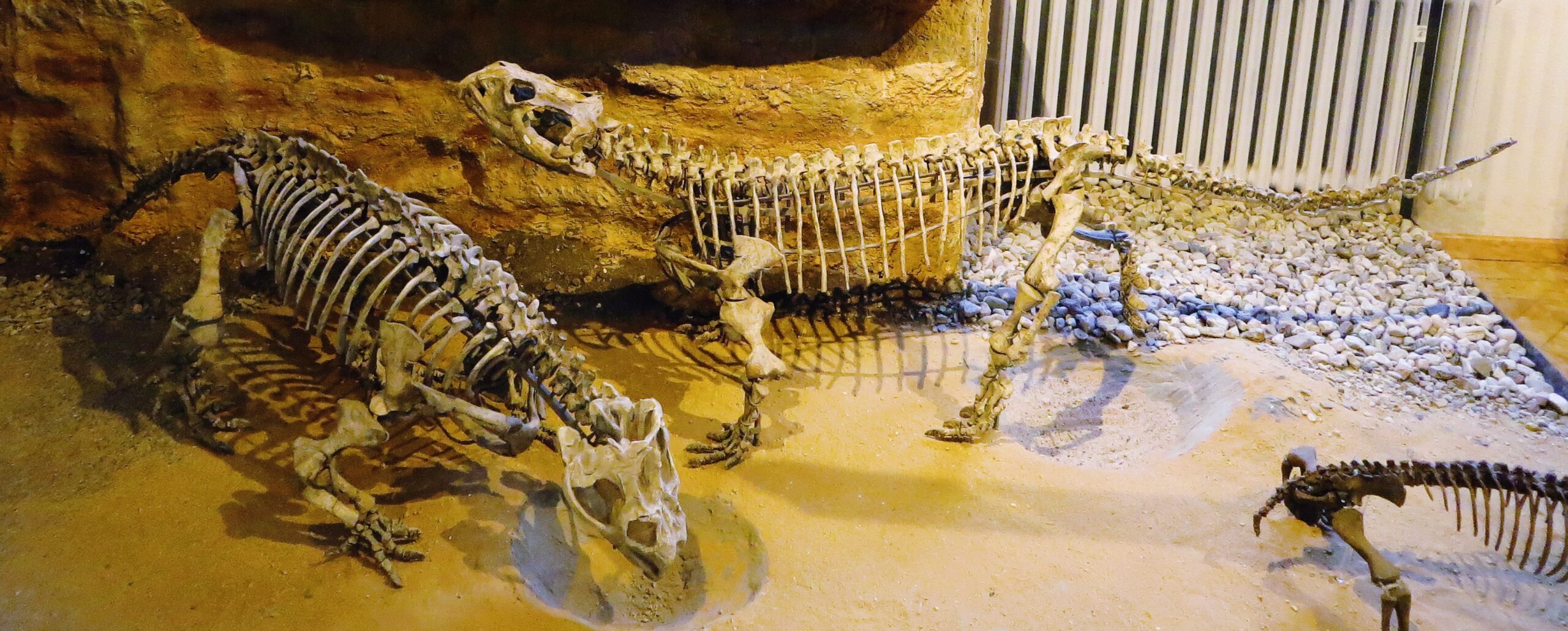

Seemingly lacking teeth, Silesaurus may have had a bird-like beak for capturing its insect prey. This wasn’t even a true dinosaur yet – it was one of their closest relatives, already experimenting with the beak design that would later become famous in birds. The fact that reptiles were developing beaks millions of years before true birds existed shows just how innovative Triassic evolution really was.

Silesaurus was a 2.3 m (7.5 ft.) long reptile that lived in Poland during the Late Triassic. It was a lightly-built, fast-moving animal that walked on its hind legs. Coprolites (fossilized droppings) found in the vicinity of Silesaurus specimens suggest that the reptile may have been an insectivore (insect eater). Imagine this beaked sprinter darting through ancient forests, snatching up insects with surgical precision.

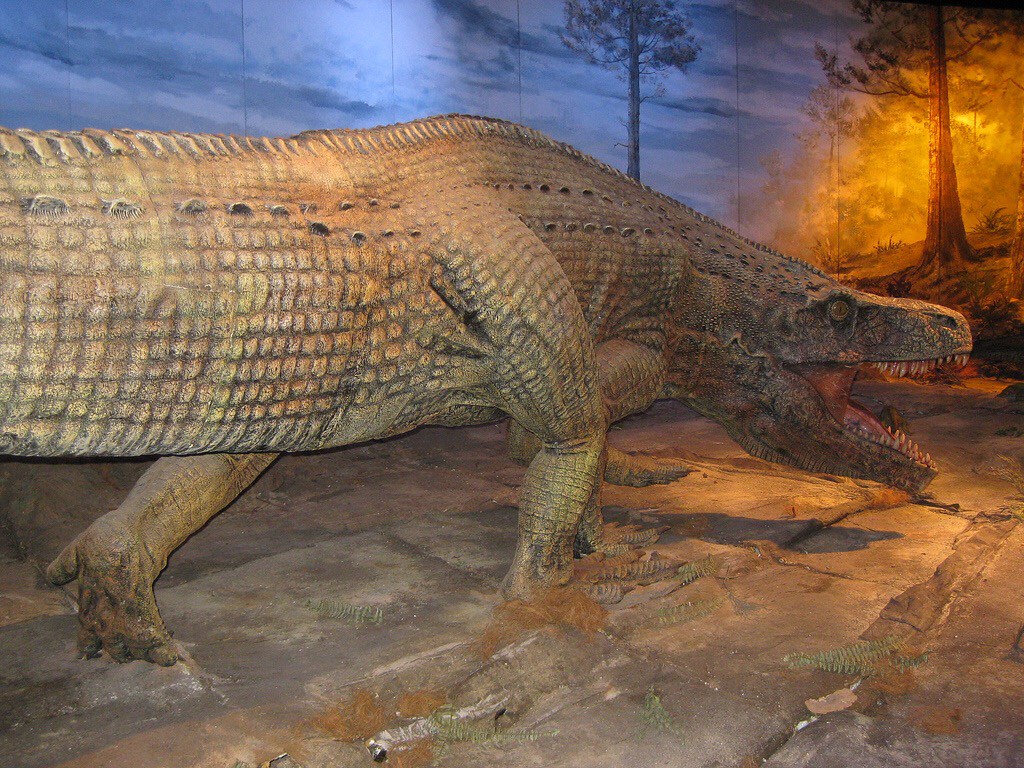

The Terrible Pseudosuchians

Before dinosaurs ruled the world, the pseudosuchians were the real kings of the Triassic landscape. In the Triassic Period the pseudosuchians were the dominant meat-eaters on land. These weren’t your typical crocodile ancestors – many were land-based super predators that would make a T. rex think twice.

With an estimated body length of 6 – 9 meters (20 – 30 ft.), Saurosuchus was a huge, crocodile-like predator of the Late Triassic Period. Saurosuchus had a mouth full of serrated teeth and armor-plated skin. It is highly likely that this fearsome reptile was an apex predator. With its relatively short fore limbs, it likely walked bipedally (on two legs). One of the largest carnivorous around at the time, it is likely to have been an apex predator.

The Chameleon-Like Tree Climbers

The drepanosaurs were a clade of unusual, chameleon-like arboreal reptiles with birdlike heads and specialised claws. These tree-dwelling weirdos looked like someone took a chameleon, gave it bird features, and then decided to add some truly bizarre modifications for good measure.

Drepanosaurs were already some extremely weird animals, even among all the other weirdos of the Triassic period. These strange little tree-climbing reptiles had chameleon-like bodies, humped backs, long necks, and oddly bird-like skulls with toothless beaks – and then some of them also had bizarre forelimb anatomy with a single enormous claw on the second finger of each hand, along with a claw on the tip of their prehensile tail. Nature was clearly having fun with the design process here.

Armored Vegetarians of the Water

The placodonts were among the most unusual marine reptiles ever discovered. The placodonts were a group of marine reptiles that lived in shallow coastal waters, and mostly ate hard-shelled prey such as mussels and other bivalves (that is, they were durophagous). They lived during the Triassic period, and have so far been found in modern-day Europe, the Mediterranean and South China.

But here’s where it gets really strange – Henodus was a placodont that lived in what is now Germany during the Late Triassic. It had a flat, square shell that was as wide as it was long. Its mouth was equipped with a flat beak and just two teeth. It may have been herbivorous, filtering plant matter from the water. Imagine a turtle-like creature with a beak that decided to become vegetarian – that’s the bizarre world of placodonts.

The First Flying Experiments

Before pterosaurs mastered true flight, the Triassic saw some fascinating early experiments with gliding. Gliding lizards, such as the small Late Triassic Icarosaurus, are thought to have developed an airfoil from skin stretched between extended ribs, which would have allowed short glides similar to those made by present-day flying squirrels. Similarly, Longisquama had long scales that could have been employed as primitive wings, while the Late Triassic Sharovipteryx was an active flyer and may have been the first true pterosaur (flying reptile).

Since all flying vertebrates today use their forelimbs as wings, it seems counterintuitive that hindlimbs could even work, aerodynamically. But the sharovipterygids, another type of basal archosaur, did exactly that. They were probably not capable of powered flight, but would have glided using membranes of skin. Talk about thinking outside the box!

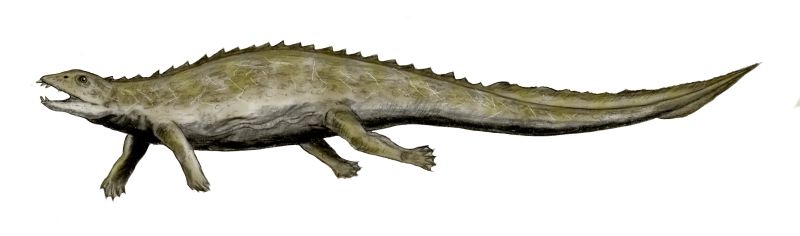

The Crocodile Imposters

Phytosaurs were large, semi-aquatic predatory reptiles that looked – and acted – like modern-day crocodiles. Their long snouts were filled with hundreds of sharp teeth, which were likely to have evolved for catching fish. But here’s the incredible part – these weren’t related to crocodiles at all! This is convergent evolution at its finest.

These animals looked quite crocodilian, but were from a different branch of the archosaurian tree. The lineage that would give rise to the crocodiles was instead represented in the Triassic by much smaller, more gracile animals. Nature had essentially created the crocodile body plan twice, completely independently. The real crocodile ancestors were probably small, agile creatures you could hold in your hands.

The Mystery Survivors and Their Fate

The Triassic wasn’t just about weird evolutionary experiments – it was also about survival and extinction. Several important clades of crurotarsans (large archosaurian reptiles previously grouped together as the thecodonts) disappeared, as did most of the large labyrinthodont amphibians, groups of small reptiles, and most synapsids. The end-Triassic extinction event was like a cosmic editor, cutting out many of nature’s most creative experiments.

Based on its relatives, Threordatoth would have been a small reptile with bony spikes on its head and potentially some bony armour on its body. I like to imagine them scampering around the sinkholes and fissures of southwest England in the Late Triassic, looking for plants and bugs to eat while avoiding the early relatives of dinosaurs. Unlike any of its relatives, each of the reptile’s teeth has three points. This is so distinctive that the researchers named the species Threordatoth which translates as ‘three-pointed teeth’ in Old English.

Conclusion

The Triassic period wasn’t just a prelude to the age of dinosaurs – it was evolution’s greatest experiment in creativity and strangeness. From hammer-headed plant-eaters with parrot beaks to marine reptiles with impossibly long necks, this era produced some of the most bizarre creatures ever to walk, swim, or glide across our planet. These weren’t failed experiments but successful adaptations to a recovering world, each finding their own unique way to thrive in the aftermath of catastrophe.

The legacy of these odd Triassic reptiles lives on in the evolutionary innovations they pioneered – beaks, extreme body proportions, and specialized hunting strategies that would influence life for millions of years to come. While most of these strange lineages didn’t survive the end-Triassic extinction, their brief moment in Earth’s spotlight reminds us that evolution’s creativity knows no bounds.

What other impossible creatures might have existed if these Triassic experiments had continued? The answer lies buried in rocks still waiting to be discovered, holding secrets of a world where reptiles truly ruled through sheer evolutionary audacity.