Imagine stumbling upon a perfectly preserved dinosaur skeleton, its bones gleaming after millions of years underground. What you’re looking at isn’t just ancient history – it’s the result of an incredible race against time that happened long before humans ever walked the Earth. Most creatures that die simply vanish without a trace, their remains devoured by scavengers or dissolved by the elements. But occasionally, something extraordinary happens that stops this natural decay process dead in its tracks.

The Great Decomposition Race

Death triggers an immediate countdown timer in nature, and it’s not a forgiving one. Within hours of an organism’s death, bacteria begin their relentless feast, breaking down soft tissues from the inside out. Scavengers arrive like cleanup crews, picking apart anything edible. Weather elements join the destruction party – rain washes away fragments, wind scatters bones, and temperature changes crack and split remains into unrecognizable pieces. This biological demolition derby happens so efficiently that most creatures leave no permanent record of their existence. The sobering truth is that fossilization is nature’s rarest accident, occurring in less than one percent of all organisms that have ever lived.

When Time Stops: The Burial Miracle

Rapid burial acts like hitting the pause button on decay, creating a protective cocoon around dead organisms before destruction can take hold. Think of it like sealing fresh food in a vacuum – without oxygen and external threats, the normal breakdown process slows to a crawl. Sediments rushing in from floods, volcanic ash falling like a blanket, or sudden landslides can bury remains within hours or days rather than years. This speed makes all the difference between preservation and disappearance. The faster the burial, the better the chances that future paleontologists will discover something incredible millions of years later.

Volcanic Catastrophes: Nature’s Preservation Chamber

Volcanic eruptions create some of history’s most spectacular fossil preservation events, turning catastrophe into scientific treasure. When Mount Vesuvius buried Pompeii in 79 AD, it demonstrated how quickly volcanic ash can preserve life in stunning detail – and the same principle applies to ancient organisms. Volcanic ash falls rapidly and creates an oxygen-free environment that halts bacterial activity almost instantly. The fine particles fill every cavity and crevice, creating detailed molds of creatures down to their smallest features. Famous fossil sites like the Burgess Shale owe their exceptional preservation to similar volcanic events that occurred over 500 million years ago.

Flood Waters: The Ultimate Fossil Factory

Massive floods rank among the most effective fossil-making machines in Earth’s history, capable of burying entire ecosystems in a matter of hours. When rivers overflow their banks or tsunamis sweep inland, they carry enormous amounts of sediment that can quickly cover deceased animals and plants. These flood events often catch organisms by surprise, preserving them in their natural poses and groupings. The famous dinosaur fossils found in places like Montana’s Two Medicine Formation tell stories of ancient floods that buried herds of creatures so quickly they remained positioned as if they were still grazing. Modern examples like the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption show us how rapidly flowing water and debris can preserve organic material for future discovery.

Mudslides and Landslides: Instant Burial Events

Landslides and mudslides represent some of nature’s most dramatic burial events, capable of entombing entire forests or animal communities in minutes. These geological avalanches often occur during heavy rains or earthquakes, when saturated soil suddenly gives way and rushes downhill like a liquid avalanche. The dense, oxygen-poor mud creates perfect conditions for preservation by sealing out bacteria and scavengers immediately. China’s famous Jehol Biota, which includes feathered dinosaurs and early birds, was preserved through repeated mudslide events that captured prehistoric life in extraordinary detail. The weight and density of the mud prevents scavengers from digging down to disturb the remains, essentially creating natural time capsules.

Tar Pits: Sticky Traps of Preservation

Tar pits and natural asphalt seeps function like prehistoric flypaper, trapping and preserving animals in ways that seem almost intentional. These sticky petroleum deposits bubble up from underground and create deceptively dangerous pools that look like harmless water from a distance. When animals become trapped, they often attract predators and scavengers who also get stuck, creating incredible concentrations of fossils in single locations. The famous La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles have yielded over one million fossils, including complete skeletons of saber-toothed cats, dire wolves, and giant ground sloths. The asphalt’s natural preservative properties keep organic material intact for tens of thousands of years, maintaining details that would normally decay within decades.

Ice Age Preservation: Frozen in Time

Freezing temperatures create some of the most spectacular preservation conditions on Earth, essentially putting biological decay on permanent hold. When organisms die in extremely cold environments, ice crystals form within their tissues and prevent bacterial decomposition from taking hold. The permafrost regions of Siberia and Alaska regularly yield mummified remains of Ice Age animals with their skin, hair, and even stomach contents intact. The famous woolly mammoth discoveries show us creatures that look like they died yesterday rather than 40,000 years ago. These frozen time capsules provide scientists with DNA, proteins, and other organic molecules that would be completely destroyed under normal fossilization conditions.

Amber: The Perfect Prison

Tree resin that hardens into amber creates the ultimate preservation medium, capturing small organisms in three-dimensional perfection that rivals museum displays. When insects, spiders, or small vertebrates become trapped in sticky resin, they’re instantly sealed in an oxygen-free environment that prevents any decay whatsoever. The resin flows around every surface, filling microscopic details and creating fossils so perfect that scientists can study individual cells and subcellular structures. Dominican amber has preserved 100-million-year-old insects so completely that their iridescent colors still shimmer under proper lighting. These amber inclusions represent the closest thing to time travel that paleontology can offer, showing us prehistoric life exactly as it appeared millions of years ago.

Deep Ocean Burial: The Underwater Cemetery

The deep ocean floor acts like a massive burial ground where rapid sedimentation can preserve marine life in remarkable detail. When organisms die in deep water, they sink through the water column and land on the seafloor where fine sediments continuously rain down from above. This constant sediment shower can bury remains within weeks or months, creating oxygen-poor conditions that halt decomposition. The famous Burgess Shale fossils were preserved through this process, capturing soft-bodied creatures that normally leave no fossil record. Cold temperatures and high pressure in deep water environments further slow bacterial activity, giving burial sediments more time to create protective layers. Modern deep-sea expeditions regularly discover preserved organic material that would have vanished completely in shallow water environments.

Desert Sandstorms: Rapid Burial in Dry Lands

Massive sandstorms in ancient deserts created unique fossilization opportunities by rapidly burying organisms in fine, dry sand that prevented normal decay processes. When powerful winds pick up enormous quantities of sand, they can bury entire landscapes within hours, creating instant time capsules of desert life. The Gobi Desert has yielded spectacular dinosaur fossils that were preserved during ancient sandstorm events, including the famous “fighting dinosaurs” specimen showing a Velociraptor and Protoceratops locked in eternal combat. Dry sand burial prevents bacterial growth while the fine particles fill every space around bones and soft tissues. These desert preservation events often capture behavioral moments that would be impossible to preserve under normal circumstances, giving us snapshots of prehistoric life in action.

Lake Bottom Preservation: Seasonal Burial Cycles

Ancient lake environments created ideal fossilization conditions through seasonal cycles of sedimentation that regularly buried organic remains throughout the year. During spring melts and heavy rains, sediment-rich water would flow into lakes and settle in distinct layers on the bottom. Organisms that died and sank to these lake floors were quickly covered by each new sediment layer, creating a geological calendar of preservation events. Germany’s Messel Pit represents one of the most famous lake burial sites, preserving 47-million-year-old mammals, birds, and insects in extraordinary detail. The regular, gentle burial process in lake environments often preserves delicate features like feathers, fur, and stomach contents that would be destroyed in more violent burial events.

Cave-In Preservation: Sudden Underground Burial

Cave collapses and sinkhole formations create unique burial environments where organisms can be rapidly entombed in rocky debris and protected from surface scavengers. When limestone caves suddenly collapse, they can trap and bury everything inside within seconds, creating sealed chambers that preserve remains for millions of years. The famous Cradle of Humankind sites in South Africa owe their exceptional hominin fossil preservation to ancient cave-in events that protected early human ancestors from the elements. Underground burial provides consistent temperatures and protection from weathering that surface burial sites cannot match. These cave preservation events often create concentrated fossil deposits where multiple individuals and species are found together, providing insights into ancient ecosystems and social behaviors.

Rapid Burial vs. Slow Decay: The Preservation Timeline

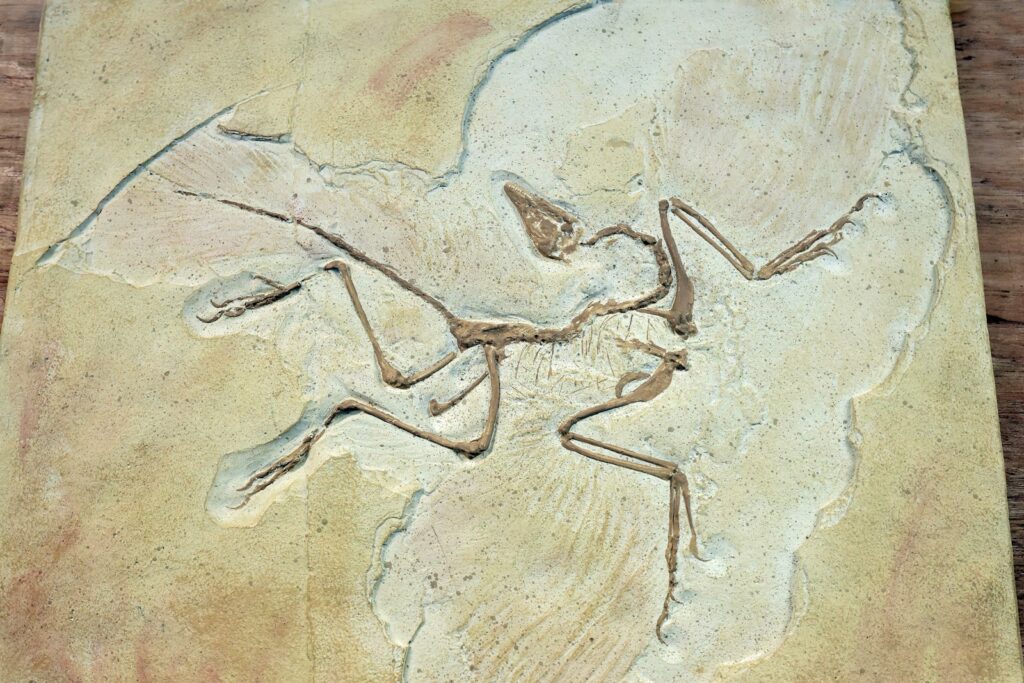

The difference between rapid burial and normal decay represents the difference between fossil preservation and complete disappearance, often measured in mere days or weeks. Scientific studies show that soft tissues begin breaking down within 24 hours of death under normal conditions, while bones can completely dissolve within decades in most environments. Rapid burial within the first few days dramatically increases preservation chances by creating anaerobic conditions before significant decay occurs. The famous Solnhofen limestone in Germany preserved pterosaurs and early birds so perfectly because burial occurred within hours of death, capturing details like wing membranes and feather impressions. This narrow window of opportunity explains why fossils are so incredibly rare despite the billions of organisms that have lived and died throughout Earth’s history.

Modern Examples: Witnessing Fossilization in Action

Contemporary natural disasters provide living laboratories where scientists can observe the fossilization process beginning in real-time, confirming theories about ancient preservation events. The 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption buried entire forests and created conditions identical to those that preserved ancient organisms millions of years ago. Hurricane deposits along modern coastlines show how rapidly moving sediments can bury and preserve organic material within hours of major storm events. Researchers studying these modern burial events have discovered that preservation quality depends entirely on burial speed – remains covered within the first 48 hours show dramatically better preservation than those buried weeks later. These observations help paleontologists understand why certain fossil sites are so exceptionally preserved while others contain only fragments and traces.

The Fossil Lottery: Why Most Life Disappears Forever

Understanding rapid burial reveals why the fossil record represents such a tiny fraction of all life that has ever existed, making each discovery incredibly precious. Most organisms live and die in environments where rapid burial is impossible – open grasslands, forest surfaces, or shallow water areas where scavengers and decomposition rule supreme. The creatures we find as fossils represent winners of an incredible geological lottery, organisms lucky enough to die in exactly the right place at exactly the right time. This rarity makes every fossil museum display a showcase of nearly impossible preservation events that happened against astronomical odds. The next time you see a complete dinosaur skeleton, remember that you’re looking at the result of a perfect storm of circumstances that occurs less than once in a million deaths – making these ancient remains some of the most precious scientific treasures on Earth.