The study of dinosaurs has captivated human imagination since the first formal scientific descriptions in the early 19th century. These magnificent creatures that once dominated Earth have been gradually revealed to us through the dedicated work of paleontologists who have spent their careers uncovering the secrets of prehistoric life. From accidental findings by amateur fossil hunters to meticulously planned excavations by research teams, dinosaur discoveries have revolutionized our understanding of evolutionary history. Each finding tells a unique story not only about the ancient reptiles themselves but also about the persistent scientists who dedicated their lives to bringing these prehistoric giants back into our collective knowledge. This article explores ten remarkable dinosaur discoveries and highlights the scientists whose determination and expertise made these findings possible.

The First Dinosaur: Megalosaurus and William Buckland

The scientific recognition of dinosaurs began in the early 1820s with William Buckland, a British geologist and clergyman. In 1824, Buckland published the first formal scientific description of a dinosaur based on fossilized jawbone fragments found in Oxfordshire, England. He named this creature Megalosaurus, meaning “great lizard,” though at the time, the term “dinosaur” had not yet been coined. Buckland initially believed Megalosaurus was a giant lizard-like creature, estimating it to be about 40 feet long. His work was groundbreaking because it acknowledged the existence of enormous reptilian creatures that predated human history, challenging prevailing views about Earth’s timeline. Buckland’s meticulous analysis of the fossil material laid the foundation for all subsequent dinosaur research, establishing paleontology as a legitimate scientific discipline rather than merely a hobby for fossil collectors.

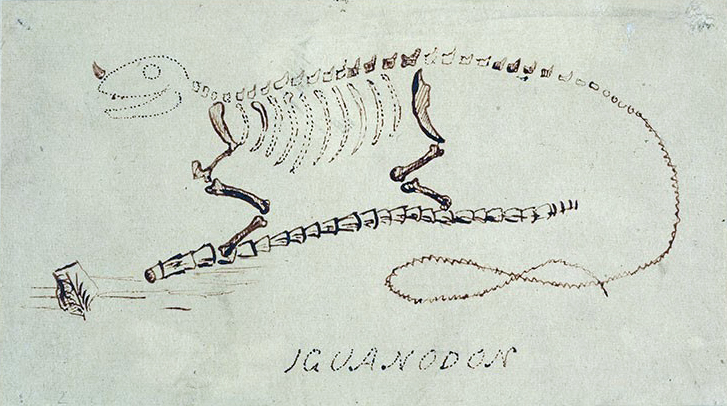

Iguanodon and Gideon Mantell’s Tenacity

The discovery of Iguanodon is often credited to Mary Ann Mantell, who reportedly found unusual teeth while walking along a country road in Sussex, England in 1822. However, it was her husband, Gideon Mantell, a physician and amateur geologist, who pursued the scientific investigation of these specimens. Despite facing ridicule from the scientific establishment, including Richard Owen, Mantell persisted in his research, eventually publishing his findings in 1825. After comparing the teeth to those of modern reptiles, Mantell concluded they belonged to a giant herbivorous reptile which he named Iguanodon, meaning “iguana tooth.” His initial reconstructions portrayed Iguanodon inaccurately as a quadrupedal lizard-like creature with a horn on its nose (which was later discovered to be a thumb spike). Despite these errors, Mantell’s dedication to studying Iguanodon against considerable scientific opposition demonstrated remarkable scientific integrity and helped establish dinosaurs as a distinct group of prehistoric animals.

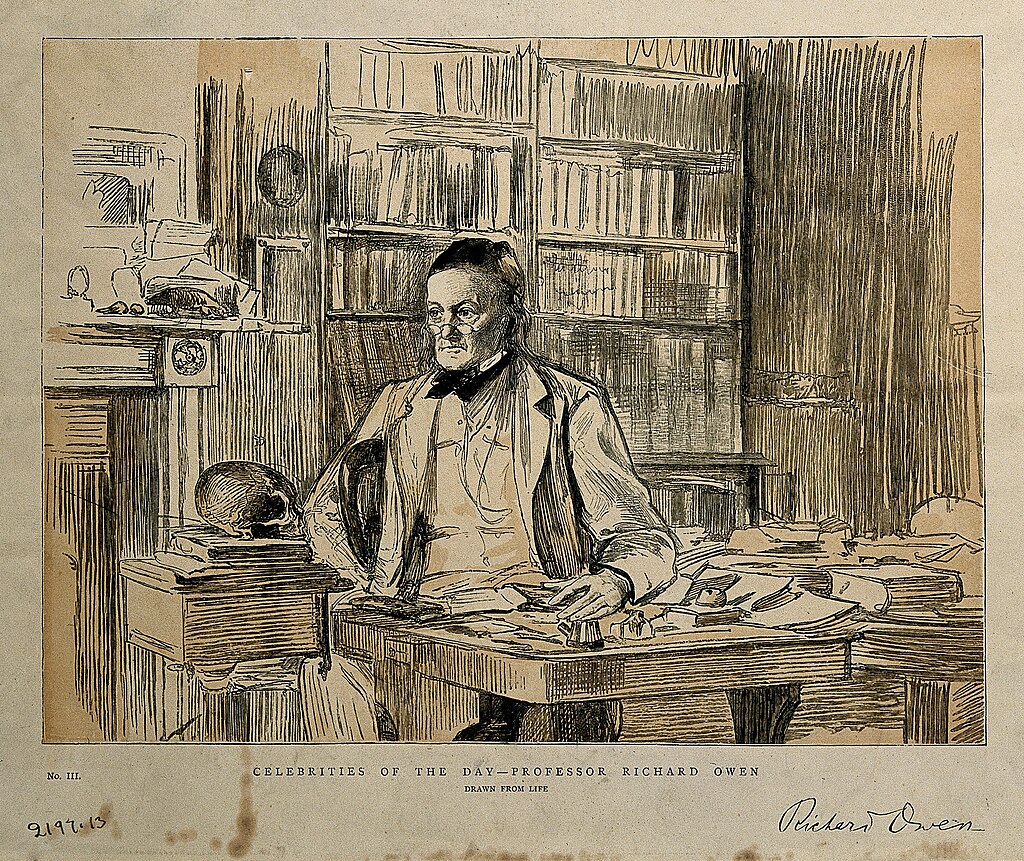

Dinosauria: Richard Owen’s Taxonomic Breakthrough

Sir Richard Owen, a brilliant British anatomist and paleontologist, made his mark on dinosaur science not through field discoveries but through conceptual innovation. In 1842, after studying fossils of Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and Hylaeosaurus, Owen recognized that these extinct reptiles formed a distinct group unlike any living animals. He created the taxonomic group “Dinosauria” (meaning “terrible lizards”) to classify these creatures, fundamentally changing how science categorized prehistoric life. Owen’s conception of dinosaurs as large, sophisticated reptiles that walked with upright posture contradicted earlier views of them as merely oversized lizards. Though some of Owen’s interpretations were later revised, his recognition of dinosaurs as a unified group was revolutionary. His influence extended beyond scientific circles when he advised on the creation of life-sized dinosaur models for the Crystal Palace exhibition in London in 1854, providing the public with their first visual conception of these ancient creatures and cementing dinosaurs in popular imagination.

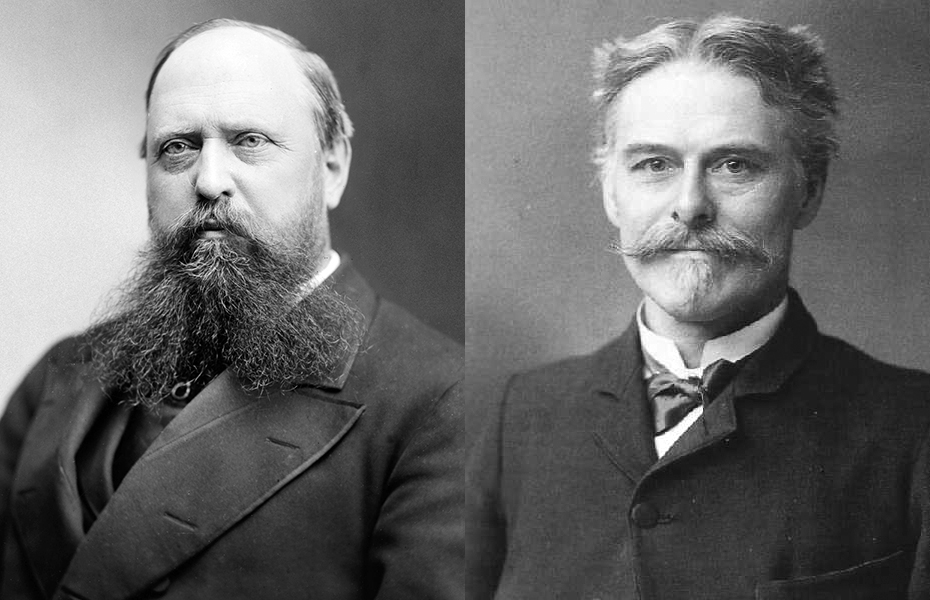

The Bone Wars: Cope, Marsh, and American Dinosaur Paleontology

The most dramatic chapter in dinosaur discovery history undoubtedly belongs to Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh, whose fierce rivalry in the late 19th century became known as the “Bone Wars.” These competing American paleontologists led expeditions throughout the American West, discovering and naming dozens of new dinosaur species including Allosaurus, Diplodocus, Stegosaurus, and Triceratops. Their bitter competition frequently descended into sabotage, theft, and public ridicule, with each rushing to publish findings before the other. Marsh, working from Yale University with financial backing from his wealthy uncle, maintained the upper hand in resources, while Cope, associated with the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, eventually depleted his inheritance funding his expeditions. Despite their destructive rivalry, their combined discoveries expanded dinosaur knowledge exponentially, with Marsh alone naming 80 new species. Their methods were often hasty and sometimes scientifically questionable by modern standards, but their collective work established America as a central hub for dinosaur paleontology and revealed the remarkable diversity of dinosaur life.

Protoceratops and Roy Chapman Andrews’s Mongolian Expeditions

In the 1920s, American explorer and naturalist Roy Chapman Andrews led a series of groundbreaking expeditions to the Gobi Desert in Mongolia for the American Museum of Natural History. These ambitious journeys, originally intended to find human ancestors, instead resulted in spectacular dinosaur discoveries. In 1922, Andrews’s team discovered numerous fossils of Protoceratops, a sheep-sized horned dinosaur that provided crucial evidence about ceratopsian evolution. Perhaps more significantly, the expeditions found the first scientifically documented dinosaur eggs in 1923, initially attributed to Protoceratops but later identified as belonging to Oviraptor. Andrews himself was a colorful character who some believe inspired the fictional Indiana Jones character, navigating political instability, sandstorms, and bandits throughout his expeditions. His team’s discoveries in Mongolia opened up Asia as a major frontier for dinosaur paleontology and demonstrated that dinosaurs had a global distribution, challenging the predominantly North American and European focus of earlier research.

Deinonychus and John Ostrom’s Dinosaur Renaissance

In 1964, Yale paleontologist John Ostrom discovered fossils of a remarkable predatory dinosaur in Montana that would transform scientific understanding of dinosaur biology. Named Deinonychus, meaning “terrible claw,” this mid-sized predator exhibited features that contradicted the prevailing image of dinosaurs as slow, cold-blooded reptiles. Ostrom’s meticulous analysis revealed Deinonychus to be agile, intelligent, and potentially warm-blooded, with a large brain relative to its body size and a distinctive sickle-shaped claw on each foot likely used for hunting. His groundbreaking 1969 monograph on Deinonychus initiated what became known as the “Dinosaur Renaissance,” a fundamental shift in how scientists viewed dinosaur physiology, behavior, and evolution. Ostrom later became a leading proponent of the theory that birds evolved from dinosaurs, noting striking similarities between Deinonychus and Archaeopteryx, the earliest known bird. His revolutionary work laid the foundation for modern understanding of dinosaurs as active, dynamic animals rather than the sluggish behemoths portrayed in earlier scientific literature and popular culture.

Sue the T. Rex and Sue Hendrickson’s Remarkable Find

One of the most famous dinosaur discoveries occurred in 1990 when amateur paleontologist Sue Hendrickson spotted bone fragments eroding from a cliff in South Dakota. Her keen eye led to the unearthing of “Sue,” the largest, most complete, and best-preserved Tyrannosaurus rex specimen ever found, with over 90% of its bones recovered. The discovery, however, soon became embroiled in legal battles over ownership rights between the fossil hunter who employed Hendrickson, the landowner, the Sioux tribe claiming ancestral rights to the land, and the federal government. After years of litigation, Sue the T. rex was sold at auction for a record-breaking $8.36 million to the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, where it remains on display. Hendrickson’s discovery not only provided scientists with unprecedented anatomical details about T. rex but also highlighted complex issues surrounding fossil ownership and commercialization. The exceptional preservation of Sue has allowed researchers to identify pathologies including broken ribs and gout, offering rare insights into the life history of this iconic predator.

Feathered Dinosaurs and Xu Xing’s Chinese Treasures

Chinese paleontologist Xu Xing has become one of the most prolific dinosaur discoverers in history, responsible for naming over 30 new dinosaur species since the late 1990s. His most significant contribution has been uncovering numerous feathered dinosaur specimens from the exceptionally preserved fossil beds of Liaoning Province in northeastern China. These specimens, including Sinosauropteryx, Yutyrannus, and Microraptor, provided definitive evidence that many dinosaurs possessed feathers, revolutionizing our understanding of dinosaur appearance and physiology. Xu’s discovery of Microraptor in 2003 was particularly groundbreaking, revealing a small dinosaur with four wings that likely glided between trees. Working primarily with the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing, Xu has been at the forefront of research confirming the evolutionary connection between dinosaurs and birds. His meticulous work has transformed our visual conception of dinosaurs from scaly reptiles to often colorful, feathered creatures, and has established China as a global center for dinosaur research, especially regarding the theropod-bird transition.

Spinosaurus and Nizar Ibrahim’s Desert Detective Work

The story of Spinosaurus, the largest known carnivorous dinosaur, involves both historical mystery and modern scientific adventure. German paleontologist Ernst Stromer originally discovered Spinosaurus fossils in Egypt in 1912, but these specimens were destroyed during World War II bombing. In 2014, paleontologist Nizar Ibrahim led efforts to rediscover this enigmatic dinosaur through remarkable detective work. Ibrahim tracked down a fossil hunter who had found Spinosaurus remains in Morocco, then located the exact excavation site in the Sahara Desert. The new fossils revealed something astounding: Spinosaurus had dense bones and short legs indicating a semi-aquatic lifestyle—the first definitive evidence of a swimming dinosaur. Ibrahim’s subsequent research, published in 2020, provided further evidence that Spinosaurus had a paddle-like tail adapted for aquatic propulsion. This discovery fundamentally changed understanding of dinosaur ecology, proving that some dinosaurs had adapted to aquatic environments rather than being exclusively terrestrial. Ibrahim’s persistence in solving the Spinosaurus puzzle across countries and continents exemplifies the sometimes detective-like nature of paleontological research.

Patagotitan and Diego Pol’s Titanosaur Team

In 2014, a rural farmer in Patagonia, Argentina, stumbled upon what would prove to be one of the largest animals ever to walk the Earth. Paleontologist Diego Pol of Argentina’s Museum of Paleontology Egidio Feruglio led the excavation team that uncovered the remains of Patagotitan mayorum, a colossal titanosaur from the late Cretaceous period. The excavation was massive in scale, involving over 40 paleontologists who recovered more than 200 fossilized bones representing six individual dinosaurs. Scientific analysis determined Patagotitan to be among the largest dinosaurs ever found, estimated to have weighed about 70 tons and measured up to 120 feet in length. Pol’s team employed 3D scanning technology to document and analyze the massive bones, which were too heavy to move using conventional methods. Their research suggested these giant titanosaurs had not yet reached their maximum size at death, indicating they could potentially have grown even larger. The discovery highlighted South America’s importance in understanding sauropod evolution and demonstrated how modern technology is enhancing paleontological research methods.

The Chicxulub Crater: Walter Alvarez and the Dinosaur Extinction Theory

While not a dinosaur discovery in the traditional sense, the work of geologist Walter Alvarez and his father, physicist Luis Alvarez, provided the most compelling explanation for dinosaur extinction. In the late 1970s, Walter Alvarez was studying rock layers in Italy when he discovered an unusual clay layer exactly at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary—the point marking dinosaur extinction 66 million years ago. Chemical analysis revealed this layer contained iridium at concentrations much higher than normally found on Earth’s surface, suggesting an extraterrestrial origin. The Alvarez team proposed that a massive asteroid impact caused a global catastrophe leading to dinosaur extinction. Their theory was initially met with skepticism until the 1990s, when scientists identified the Chicxulub crater in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula as the impact site. This 110-mile-wide crater matched the timeline of dinosaur extinction perfectly. Walter Alvarez’s persistence in investigating this extinction event transformed our understanding of Earth’s history, demonstrating how sudden catastrophic events can dramatically alter the course of evolution, ending the 165-million-year reign of non-avian dinosaurs and allowing mammals to diversify into newly vacant ecological niches.

The Legacy and Future of Dinosaur Discovery

The history of dinosaur discoveries illustrates how scientific understanding evolves through a combination of careful observation, technological innovation, and sometimes pure serendipity. From William Buckland’s initial Megalosaurus description to the latest findings using CT scanning and molecular paleontology, each discovery has built upon previous knowledge while sometimes completely upending established theories. Modern paleontologists now employ sophisticated tools including ground-penetrating radar to locate fossils, synchrotron radiation to examine internal structures, and computer modeling to study biomechanics and behavior. The democratization of paleontology has also expanded, with citizen scientists making significant contributions and digital platforms allowing global collaboration on fossil analysis. Despite over 200 years of dinosaur research, new species continue to be discovered at a remarkable rate—approximately 50 new dinosaur species are named each year. As paleontologists venture into previously unexplored regions of Africa, Asia, and South America, and develop new analytical techniques, our understanding of dinosaur diversity, behavior, and evolution continues to expand, demonstrating that the golden age of dinosaur discovery is not behind us but still very much underway.

The scientists highlighted in this article represent just a fraction of the dedicated researchers who have contributed to our understanding of dinosaurs. Their discoveries not only revealed individual species but often transformed entire paradigms about prehistoric life. From Buckland’s pioneering descriptions to Ibrahim’s detective work in the Sahara, these paleontologists demonstrate that science advances through persistence, innovation, and a willingness to challenge established ideas. As new generations of researchers apply cutting-edge technologies to the study of fossils, we can expect even more revolutionary dinosaur discoveries in the decades to come, continuing to rewrite the extraordinary story of Earth’s most magnificent extinct creatures.