In the annals of paleontology, we often celebrate the scientists who analyze and interpret ancient remains, while overlooking those who initially discovered these prehistoric treasures. Behind many groundbreaking fossil discoveries stand individuals whose names rarely grace museum placards or textbook pages. These unsung heroes—from amateur collectors to field assistants—have fundamentally altered our understanding of Earth’s history through their keen eyes, persistence, and sometimes sheer luck. This article highlights six remarkable individuals whose fossil finds revolutionized paleontology, yet whose contributions remain largely uncelebrated in popular science narratives.

Mary Anning: The Working-Class Woman Who Revolutionized Marine Paleontology

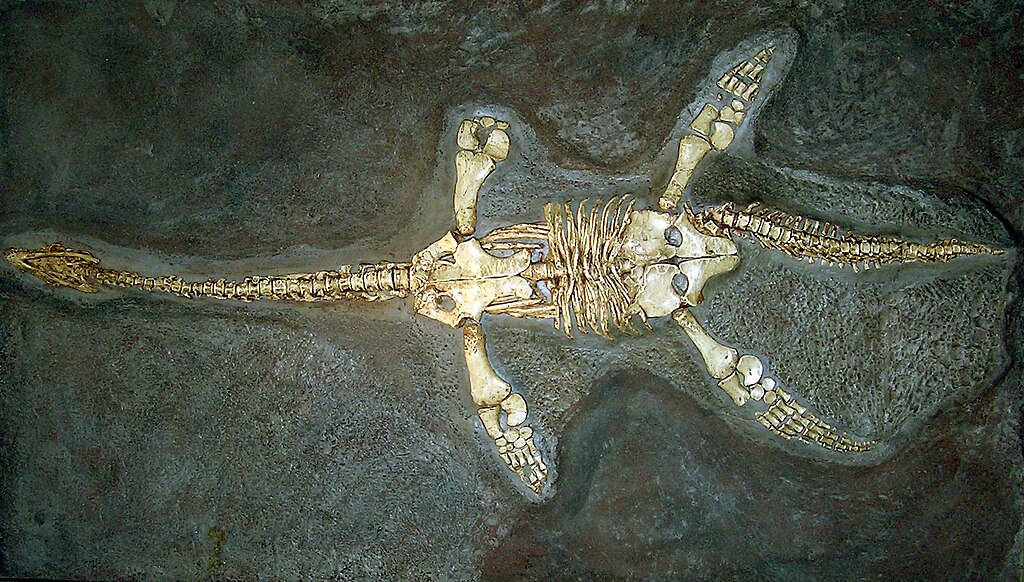

While Mary Anning has gained some recognition in recent years, she spent most of history overlooked despite her extraordinary contributions. Born in 1799 to a poor family in Lyme Regis, England, Anning supported herself by collecting and selling fossils along the dangerous Jurassic Coast cliffs. Her most significant finds included the first complete ichthyosaur skeleton recognized by science, a plesiosaur, and a pterosaur—all before she turned thirty. What makes Anning’s story particularly remarkable is that despite her lack of formal education and the scientific community’s gender barriers, her meticulously prepared specimens and keen observations fundamentally shaped early paleontology. Male scientists frequently published work based on her discoveries without crediting her, and the Geological Society of London wouldn’t even allow her to attend meetings as a guest during her lifetime.

Mick Ellison: The Artist Who Brings Dinosaurs to Life

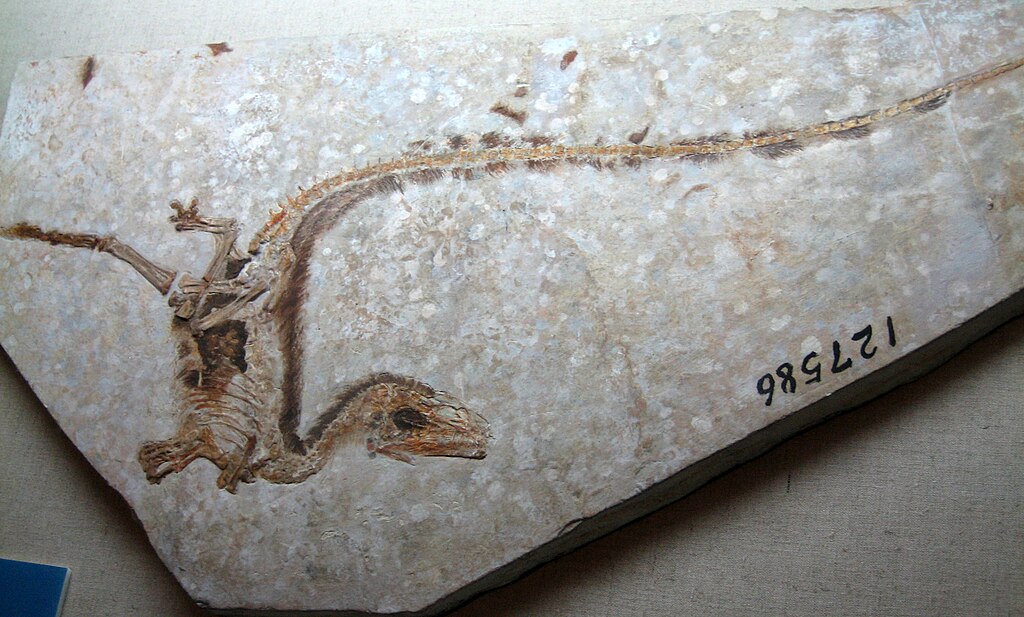

While paleontologists get the bylines on scientific papers, scientific illustrators like Mick Ellison quietly revolutionize how we visualize extinct creatures. As the principal artist at the American Museum of Natural History’s paleontology department, Ellison has spent decades creating photorealistic reconstructions of dinosaurs that blend rigorous scientific accuracy with artistic vision. His groundbreaking illustrations of feathered dinosaurs from China’s Liaoning Province helped transform public understanding of dinosaur appearance. Ellison doesn’t just draw what scientists tell him—he participates in expeditions, photographs specimens using specialized lighting techniques to reveal hidden features, and often notices anatomical details that even researchers miss. His technical innovations in fossil photography and digital reconstruction have become standard practice in the field, yet his name remains unfamiliar outside professional circles despite his visuals appearing in countless publications and exhibits worldwide.

Susan Hendrickson: The Self-Taught Explorer Behind “Sue”

In 1990, the world’s most complete Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton was discovered in South Dakota—a specimen that would later be named “Sue” after its finder, Susan Hendrickson. What many don’t realize is that Hendrickson had no formal scientific training when she made this historic discovery. A self-taught explorer with an exceptional eye for detail, Hendrickson spotted several vertebrae eroding from a cliffside that the rest of her expedition team had overlooked during a tire repair stop. This chance observation led to the unearthing of a T. rex skeleton that was 90% complete, revolutionizing our understanding of this iconic dinosaur’s anatomy. Despite this monumental contribution to paleontology, Hendrickson’s name is often reduced to a footnote, while the $8.4 million fossil (the highest price ever paid for a fossil at that time) became a centerpiece at Chicago’s Field Museum. Hendrickson went on to make significant discoveries in entomology and marine archaeology, but rarely receives public recognition proportionate to her contributions.

William Walker: The Yorkshire Miner Who Found an Ancient Sea Monster

In 1960, amateur fossil hunter William Walker was exploring the cliffs near Whitby, England, when he noticed something unusual protruding from the shale. Rather than extracting the specimen himself, Walker reported his find to the Hull Museum, setting in motion what would become one of the most significant marine reptile discoveries in British paleontology. The fossil turned out to be an extraordinarily complete plesiosaur, now known as the Speeton Clay Sea Dragon. What makes Walker’s contribution particularly significant is not just his initial discovery, but his meticulous documentation of the site and careful approach to preservation. Unlike many amateur collectors of his era who might have damaged specimens during extraction, Walker understood the scientific importance of professional excavation. The subsequent scientific analysis revealed new details about plesiosaur anatomy and marine ecosystems of the Early Cretaceous period. Despite this contribution, Walker remained relatively anonymous, continuing his work as a coal miner while making numerous other significant fossil finds that enriched regional museums.

Bai Yicong: The Farmer Who Transformed Our Understanding of Dinosaur Evolution

In rural Liaoning Province, China, farmer Bai Yicong had no background in paleontology when he discovered strange impressions in the rocks on his land in the early 1990s. These turned out to be exquisitely preserved fossils of feathered dinosaurs that would fundamentally challenge scientists’ understanding of bird evolution. Bai’s discovery of what would later be identified as Sinosauropteryx—the first non-avian dinosaur confirmed to have feathers—sparked a revolution in paleontology. The Liaoning fossils provided critical evidence for the evolutionary link between dinosaurs and birds, confirming a theory that had been debated for over a century. Despite the monumental importance of these finds, Bai received minimal compensation and little recognition beyond his local community. The economic circumstances in rural China meant that many farmers like Bai sold their discoveries to middlemen for modest sums, never knowing the scientific significance of what they had found or receiving proper credit in scientific publications.

Joe Taylor: The Fossil Preparator Who Brings Bones Back to Life

Behind every magnificent dinosaur skeleton in a museum stands a fossil preparator—a skilled technician who meticulously removes the surrounding rock and stabilizes fragile remains. Joe Taylor of Crosbyton, Texas, represents one of the most skilled yet underrecognized professionals in this field. Since the 1970s, Taylor has prepared some of the most significant dinosaur specimens in North America, including several T. rex skeletons and the Acrocanthosaurus at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. What distinguishes Taylor’s work is not just his technical precision but his innovations in preparation methods. He pioneered several techniques for fossil casting and preservation that are now standard practice in museums worldwide. Additionally, Taylor has trained countless preparators who now work in major institutions, extending his influence throughout the field. Despite fossil preparators spending thousands of hours on specimens that scientists later analyze and publish about, their names rarely appear in scientific papers or museum displays, rendering their crucial contributions largely invisible to the public.

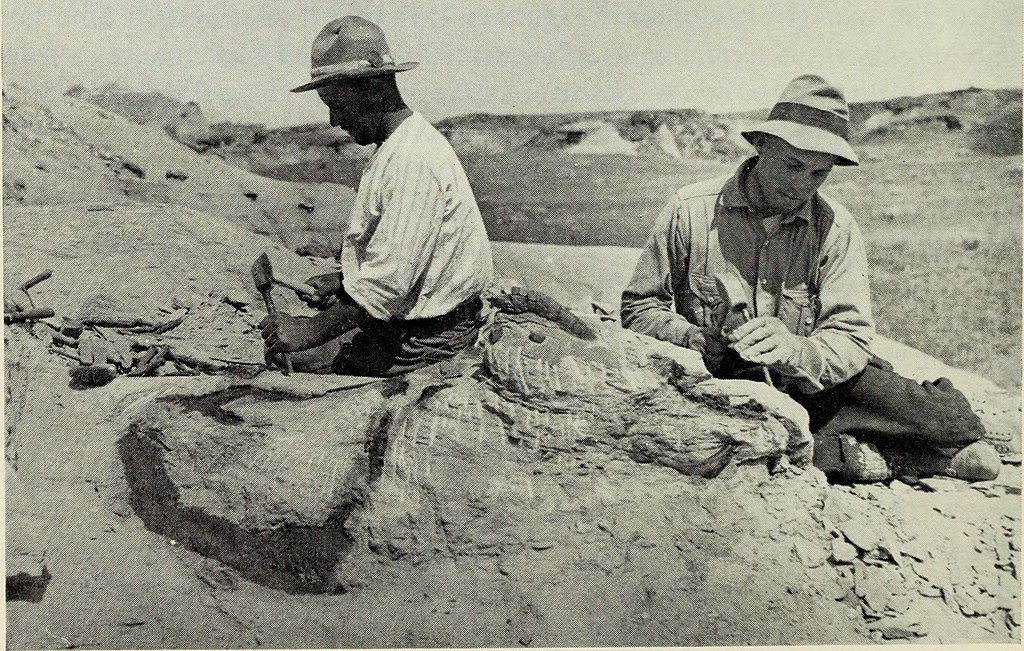

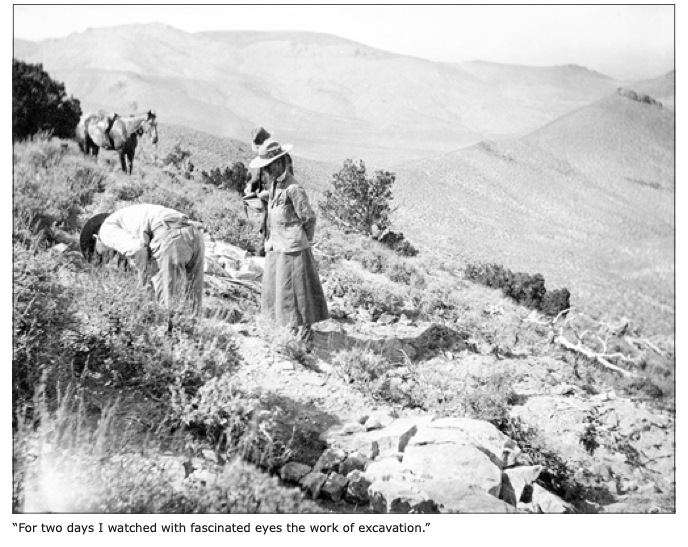

The Critical Role of Field Assistants in Major Expeditions

Behind every celebrated paleontologist stands a team of field assistants whose labor and expertise make discoveries possible. These individuals—often local guides, laborers, or graduate students—perform the most physically demanding aspects of fieldwork under challenging conditions. Consider the Tendaguru expedition in German East Africa (now Tanzania) from 1909-1913, which yielded spectacular dinosaur specimens including Brachiosaurus. While the German scientists received accolades, over 500 local workers who excavated, transported, and packed fossils through difficult terrain remain nameless in scientific literature. Similarly, the famous expeditions to Mongolia’s Gobi Desert in the 1920s relied heavily on Mongolian and Chinese assistants who navigated treacherous landscapes and identified fossil-bearing formations. These individuals possessed invaluable knowledge of local geology and terrain that was essential to the expeditions’ success, yet their contributions were frequently minimized in expedition accounts that centered Western scientists.

The Economic Realities of Fossil Hunting

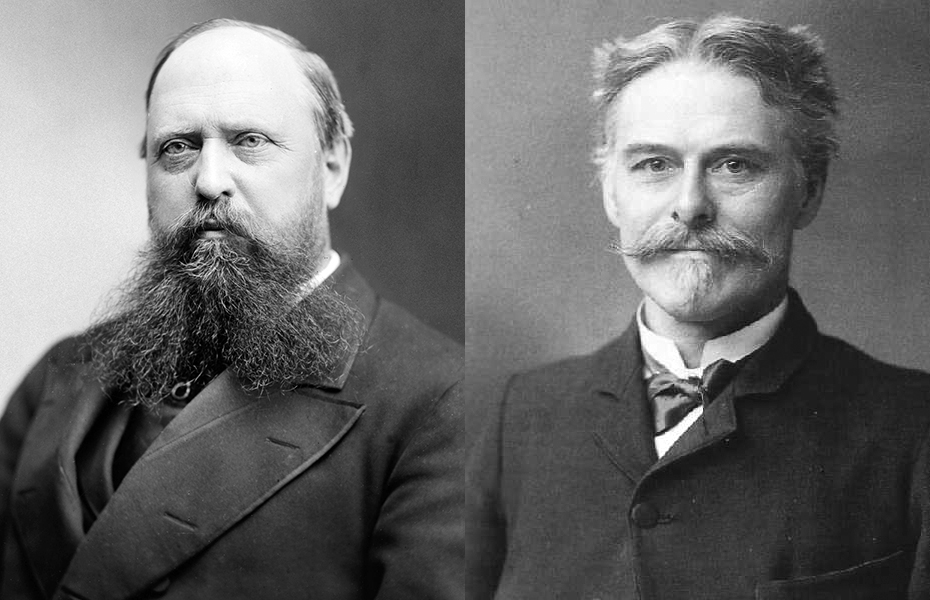

For many unsung fossil discoverers, economic necessity rather than scientific ambition drove their contributions to paleontology. The commercial fossil trade has long occupied a controversial position within scientific circles, yet many significant specimens were initially discovered by individuals hunting fossils for financial survival. The 19th-century “Bone Wars” between paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope relied heavily on hired collectors who worked in dangerous conditions for modest pay. These collectors—including people like Arthur Lakes, William Reed, and John Bell Hatcher—made numerous groundbreaking discoveries but received fraction of the recognition afforded to the wealthy scientists who employed them. Even today, commercial fossil hunters operate in a complex space between science and commerce, sometimes making crucial discoveries while struggling to make a living. Many significant specimens in major museums were purchased from commercial collectors whose names have been lost to history, despite their expert knowledge of fossil-bearing formations and extraction techniques.

Women in Early Paleontology: Hidden Contributors

Beyond Mary Anning, numerous women made significant paleontological contributions while receiving minimal recognition due to gender barriers in science. Annie Montague Alexander funded and led fossil-hunting expeditions throughout the western United States in the early 20th century, personally discovering numerous important specimens that formed the foundation of the University of California Museum of Paleontology. Despite her scientific expertise and field leadership, she was often described merely as a “patron” rather than a scientist. Similarly, Tilly Edinger established the field of paleoneurology—the study of brain evolution through fossil evidence—while working in extremely difficult circumstances as a Jewish scientist in Nazi Germany before her eventual escape to America. Her groundbreaking work on endocranial casts revolutionized understanding of vertebrate brain evolution, yet her contributions remain under-recognized compared to her male contemporaries. These women often worked without institutional support, formal positions, or access to scientific societies, making their accomplishments all the more remarkable.

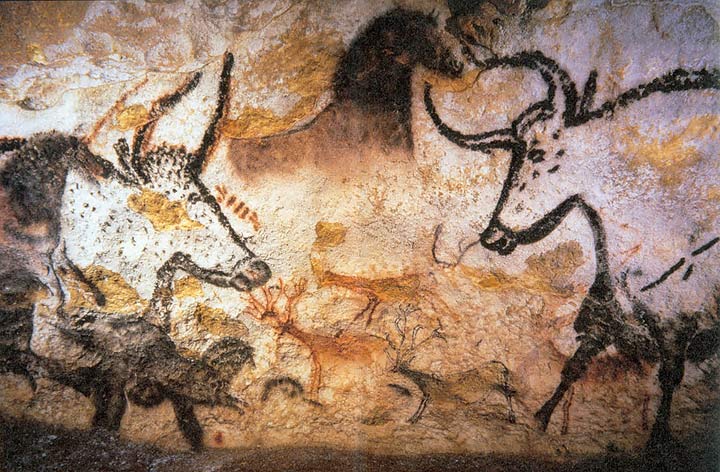

Teenage Discoverers: Young Eyes Making Ancient Finds

Some of paleontology’s most significant discoveries have come from teenagers whose keen observations led to major scientific breakthroughs. In 1938, 15-year-old Francois Héritier was exploring with friends near Montignac, France, when their dog Robot fell into a hole. While attempting to rescue the dog, the teenagers discovered what would become known as the Lascaux Cave, containing some of the world’s most important Paleolithic art. Similarly, in 1965, 14-year-old Raymond de Saussure discovered dinosaur footprints while hiking in the French Alps—tracks that would later prove crucial to understanding dinosaur behavior. More recently, in 2009, 10-year-old Kathryn Aurora Gray discovered a supernova while examining astronomical images with her father, becoming the youngest person ever to make such a discovery. These young discoverers share a common trait—the ability to notice anomalies that even trained scientists might overlook. Their discoveries challenge the notion that significant scientific contributions require advanced degrees or professional status, demonstrating how curious minds at any age can advance our understanding of the natural world.

The Indigenous Knowledge Gap in Paleontological History

Long before Western science formalized paleontology, indigenous communities around the world had discovered, interpreted, and preserved knowledge about fossils. Native American tribes across North America incorporated fossil finds into their cultural traditions and knowledge systems centuries before European settlers arrived. The Sioux, Crow, and Blackfoot peoples identified areas rich in dinosaur remains, often incorporating these “giant bones” into their oral traditions and cultural practices. Similarly, in Australia, Aboriginal communities had extensive knowledge of megafauna fossils that they integrated into their Dreamtime stories. When Western paleontologists “discovered” these fossil sites in the 19th and 20th centuries, they rarely acknowledged that indigenous peoples had identified and interpreted these remains generations earlier. This erasure represents one of paleontology’s most significant blind spots—the failure to recognize indigenous communities as the original paleontologists in many regions. Recent efforts to incorporate traditional ecological knowledge into scientific research have begun addressing this historical imbalance, though much work remains to properly credit indigenous contributions to our understanding of Earth’s prehistoric life.

The Legacy of Unsung Fossil Finders Today

The pattern of overlooking crucial contributors continues in modern paleontology, though efforts to address this imbalance are increasing. Today’s unsung heroes include laboratory technicians who perform critical analyses, museum preparators who spend thousands of hours revealing fossil details, and local field assistants in countries from Morocco to Mongolia whose expertise guides researchers to productive sites. The rise of social media and digital publishing has created new opportunities for recognition, with some institutions now making concerted efforts to acknowledge all team members involved in significant discoveries. Citizen science projects like the Fossil Atmospheres Project at the Smithsonian and digital platforms like myFOSSIL are democratizing participation in paleontology, allowing broader contribution while ensuring proper attribution. Nevertheless, structural inequalities in science continue to determine whose contributions receive recognition and whose remain in the shadows. By acknowledging the full spectrum of individuals who advance paleontological knowledge—from those with doctoral degrees to those with sharp eyes and shovels—we gain a more complete and equitable understanding of how we’ve come to know Earth’s ancient past.

Conclusion: Redefining What Makes a Paleontological Hero

The history of fossil discovery reminds us that groundbreaking scientific contributions often come from unexpected sources. The unsung heroes highlighted in this article—from Mary Anning’s self-taught expertise to Bai Yicong’s farmer’s perspective—demonstrate that paleontological progress depends on diverse skills and backgrounds extending far beyond academic credentials. By broadening our recognition beyond the scientists who publish papers to include those who first spot unusual shapes in rock faces, carefully extract fragile specimens, or prepare fossils with painstaking precision, we develop a more accurate picture of how scientific knowledge actually advances. As museums and educational institutions increasingly acknowledge these previously overlooked contributors, they not only correct historical oversights but also inspire a more inclusive vision of who can participate in scientific discovery. The next world-changing fossil find could come from anyone—a child exploring a riverbank, a construction worker noticing something unusual at an excavation site, or a hiker venturing off the beaten path—continuing the long tradition of unexpected discoveries that have shaped our understanding of life’s ancient history.