Picture this: a massive predator longer than a school bus, equipped with a towering six-foot sail that jutted from its back like nature’s most dramatic mohawk. This wasn’t just any dinosaur – this was Spinosaurus, possibly the largest carnivorous dinosaur to ever walk the Earth. For over a century, scientists have been scratching their heads trying to figure out why evolution gave this aquatic giant such an eye-catching piece of anatomy. Was it a giant radiator? A flashy dating advertisement? Or perhaps nature’s version of a swimming fin?

The Great Spinosaurus Sail Mystery

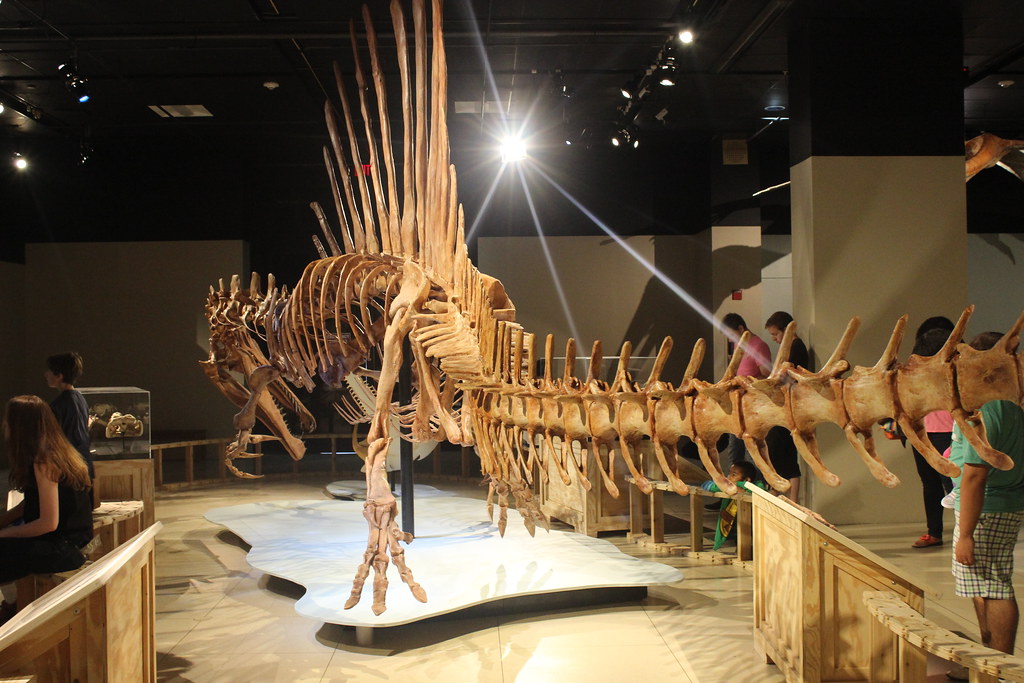

The impressive sail on Spinosaurus’ back has sparked more scientific debates than almost any other dinosaur feature. The distinctive neural spines grew to at least 1.65 meters long and were up to 10 times the diameter of the vertebral bodies from which they extended. Think of it like having a fence post that’s ten times longer than it is wide – that’s some serious structural engineering.

What makes this mystery even more intriguing is that we’re dealing with incomplete evidence. For over 100 years scientists only had very incomplete remains of this dinosaur, and the original bones from 1912 were destroyed during World War II bombing raids in 1944. It’s like trying to solve a jigsaw puzzle when half the pieces got blown up in a bombing raid.

Theory One: The Ultimate Temperature Control System

The most traditional explanation for Spinosaurus’ sail centers on thermoregulation – essentially, it was a living air conditioner and heater rolled into one. Multiple functions have been put forward for the dorsal sail, including thermoregulation, and this theory has some serious scientific backing.

The structure may have been used for thermoregulation, and if it contained abundant blood vessels, the animal could have used the sail’s large surface area to absorb heat, implying the animal was only partly warm-blooded and lived in climates where night-time temperatures were cool. Picture a massive solar panel on Spinosaurus’ back, soaking up the morning sun to kickstart its metabolism for the day ahead.

However, recent research throws a wrench into this neat explanation. The sail had supplementary roles as a mechanism of thermoregulation, proving efficient for retaining thermal energy but ineffective in dissipating heat. So while it might have worked great as a heater, it would’ve been pretty useless as a cooler – not ideal for a giant predator living in hot North African climates.

Theory Two: The Original Dating Profile

Sometimes the most obvious answer is the right one, and when it comes to bizarre animal features, reproduction often takes center stage. Multiple functions have been put forward for the dorsal sail, including display to intimidate rivals or attract mates. Think of it as nature’s equivalent of a flashy sports car or an expensive watch – pure showing off.

Many theories have been proposed for the use of spinosaurid dorsal sails for display purposes such as intimidating rivals and attracting mates, with many elaborate body structures of modern-day animals serving to attract members of the opposite sex during mating, making it possible that the sail of Spinosaurus was used for courtship like a peacock’s tail. The comparison to peacocks isn’t just wishful thinking – in 1915, Stromer speculated that the size of the neural spines may have differed between males and females.

This theory gets even more compelling when you consider the behavioral implications. The dinosaur’s massive sail may have been part of a ritual dance used to intimidate rivals, much like modern peacocks use their tails to impress potential mates. Just imagine a 50-foot-long predator doing a dramatic courtship dance with its six-foot sail catching the sunlight – definitely not something you’d want to interrupt.

Theory Three: The Aquatic Advantage

Here’s where things get really interesting. Unlike most dinosaurs, Spinosaurus was a water-loving giant, and some scientists think that massive sail might have been an aquatic adaptation. The sail may even have helped to propel the dinosaur through water, functioning like a living dorsal fin.

The submerged sail would have improved maneuverability and provided the hydrodynamic fulcrum for powerful neck and tail movements, with the size and shape of the spinal sail resembling the anatomical geometry of the dorsal fins of sailfish. The sailfish comparison is particularly fascinating because these modern fish are among the ocean’s most efficient predators, using their sails for both speed and hunting precision.

Some researchers have proposed even more dramatic aquatic functions. The sail could have been employed as a screen for encircling prey underwater, essentially turning Spinosaurus into a living fishing net. Picture this massive predator using its sail to corral schools of fish into a tight space before snapping them up with its crocodile-like jaws.

The Multi-Purpose Marvel

Modern science rarely settles for single-function explanations, and the Spinosaurus sail might be no exception. It is probable that the sail had supplementary roles, acting both as a mechanism of thermoregulation and hydrodynamics, proving efficient for retaining thermal energy and functioning in moderately aiding Spinosaurus in roaming through waters near the shoreline.

This multi-function approach makes evolutionary sense. Why settle for just one benefit when you can have several? The sail could have served as a temperature regulator in the morning, a display structure during mating season, and a swimming aid when hunting in rivers and coastal waters.

It is likely that the sail served the crucial function of display since it would have a large surface area and could be a distinguishable characteristic that could determine mating success. But that doesn’t mean it couldn’t pull double or triple duty as needed.

Sail or Hump? The Shape Debate

Not all scientists agree that Spinosaurus even had a traditional sail. The structure may have been more hump-like than sail-like, with Bailey arguing that the spines were similar to those of extinct hump-backed mammals like Megacerops and Bison latifrons. Imagine Spinosaurus looking less like a sailfish and more like a massive, carnivorous buffalo.

Some scientists have speculated that Spinosaurus had a thick, fleshy hump rather than a thin sail, but the latest research suggests that a thin sail is most likely. The hump theory would completely change our understanding of the structure’s function – fat storage makes more sense for surviving lean times than for swimming or display.

In 2014, researchers posited that the spines were covered tightly by skin, similar to a crested chameleon, given their compactness and sharp edges. This would suggest a thinner, more flexible structure than a fat-filled hump but perhaps not as dramatic as the traditional sail reconstruction.

Living Analogies: What Modern Animals Tell Us

When trying to understand extinct creatures, scientists often look to modern animals for clues. Living reptiles with similar spine-supported sails over trunk and tail are used for display rather than aquatic propulsion. This strongly supports the display hypothesis over the swimming theory.

Modern chameleons provide particularly compelling parallels. Their crests serve primarily for visual communication – establishing dominance, attracting mates, and warning rivals. If Spinosaurus’ sail functioned similarly, it would have been like wearing a giant neon sign announcing “I’m big, I’m bad, and I’m available for mating.”

The sailfish comparison, while tempting, might not hold water (pun intended). Nearly all extant secondary swimmers have reduced limbs and fleshy tail flukes, features that Spinosaurus notably lacked. This suggests that despite its aquatic adaptations, it wasn’t built for high-speed swimming like modern marine predators.

The Behavioral Implications

If the sail was primarily for display, this tells us fascinating things about Spinosaurus behavior. Scientists hypothesize that it could have been used in displays to intimidate rivals or attract mates, with physical combat between individuals being plausible. This suggests these giants had complex social lives, not just simple predator-prey relationships.

The sail could be a mock spine that could put off an attacking dinosaur, making Spinosaurus look bigger than it actually was to intimidate predators, and perhaps helping protect the vulnerable back and neck. Given that Spinosaurus shared its world with other massive predators like Carcharodontosaurus, intimidation would have been a valuable survival tool.

The flexibility of the spines also suggests behavioral complexity. There is significant evidence that their spines were flexible, making it easy to arch their backs, and they may have used their sails to regulate body temperature by storing access fat or absorbing heat. A flexible sail opens up possibilities for dynamic displays – imagine Spinosaurus raising and lowering its sail like a living billboard.

Environmental Context: Life in Cretaceous North Africa

Understanding the sail’s function requires understanding Spinosaurus’ world. It lived in a humid environment of tidal flats and mangrove forests alongside many other dinosaurs, as well as fish, crocodylomorphs, lizards, turtles, pterosaurs, and plesiosaurs. This was a crowded ecosystem where visual communication would have been crucial.

At that time, its North African habitat consisted of tidal flats and mangrove forests, with the hottest time of year bringing long droughts that would cause many lakes and rivers to dry up, potentially forcing Spinosaurus to sometimes act as a land predator. A multi-function sail would have been incredibly valuable in such a variable environment.

The seasonal changes in water levels might explain why the sail needed to serve multiple purposes. During high water periods, it could aid in aquatic hunting. During dry seasons, it might have been more important for thermoregulation and social signaling as multiple Spinosaurus competed for limited water sources.

The Latest Research Revelations

Recent technological advances have provided new insights into this ancient mystery. Recent research suggests that the large tail fin was probably utilized more for display than swimming, as tails in living animals have the same function when they possess comparably tall neural spines. This extends the display function beyond just the back sail to the entire spinal column.

A 2022 Nature study showed that Spinosaurus had dense bones to use as ballast for diving like a penguin, but other research claimed both species would have been unstable when swimming at the surface and far too buoyant to dive and fully submerge. These conflicting findings highlight just how complex and controversial Spinosaurus research remains.

Recent literature reviews examining Spinosaurus’ dorsal sail regarding its function as thermoregulation, display, or hydrodynamic show that the function has been widely debated, with the three most popular hypotheses being thermoregulation, display, or hydrodynamic. Even with modern technology, scientists haven’t reached a consensus.

Conclusion: The Enduring Enigma

After more than a century of study, the function of Spinosaurus’ magnificent sail remains one of paleontology’s most intriguing puzzles. Based on existing research, we cannot conclude that there is a definitive primary function – and perhaps that’s the point. Evolution rarely produces single-purpose solutions, especially for such a dramatic anatomical feature.

The most likely scenario is that this remarkable structure served multiple functions throughout the animal’s life. Morning thermoregulation, afternoon swimming assistance, and evening mating displays – why not all three? In a world where survival meant adapting to changing water levels, competing with other giant predators, and successfully reproducing, a multi-purpose sail would have been the ultimate evolutionary advantage.

What makes this mystery so captivating is that it forces us to imagine these ancient giants not as simple movie monsters, but as complex living beings with sophisticated behaviors and adaptations. The next time you see a Spinosaurus reconstruction, remember that you’re looking at one of evolution’s most creative solutions to the challenges of life in Cretaceous North Africa. Pretty impressive for a 99-million-year-old mohawk, wouldn’t you say?