Picture this: you’re standing in a time machine, looking back through millions of years of Earth’s history. What you’d see might shock you – massive creatures roaming landscapes we can barely imagine, entire ecosystems functioning in ways that challenge everything we thought we knew about nature. These ancient worlds weren’t just backdrops to dinosaur movies; they’re actually treasure troves of knowledge that could help us save our planet today.

The Living Library of Ancient Life

Fossilized leaves, seeds, and wood offer clues about the types of plants that once thrived, while impressions of animal tracks and burrows reveal the presence of ancient inhabitants. Advances in technology, such as CT scanning and isotopic analysis, have allowed scientists to reconstruct these lost worlds with greater accuracy. Think of these ancient ecosystems as Earth’s oldest library, where each fossil is a book telling us how life once flourished.

What makes this knowledge so valuable isn’t just the cool factor of discovering what a 300-million-year-old forest looked like. The study of prehistoric forests offers valuable lessons for modern conservation efforts. By understanding the dynamics of these ancient ecosystems, we can gain insights into the processes that drive biodiversity and ecosystem resilience. It’s like having a manual for how nature actually works when left to its own devices.

Climate Change Lessons from the Deep Past

Our ancestors in the field of conservation paleobiology have discovered something remarkable: Using tools such as precisely-dated fossil records, genome-scale ancient DNA, and sophisticated predictive modeling, researchers reconstructed prehistoric species distributions and climate conditions and deduce how ancient ecosystems responded to past climate change. They found that individual organisms responded variably and independently to climate shifts, resulting in landscapes with shifted biome boundaries and novel species assemblages following climate change.

This isn’t just academic curiosity. Geohistorical records from times in the past when the climate was warmer may be especially useful at present. When we’re facing our own climate crisis, understanding how species and ecosystems handled massive temperature swings in the past gives us a roadmap for what might happen next. It turns out that nature is both more resilient and more vulnerable than we might have expected.

The Rise and Fall of Ancient Giants

The Carboniferous period, and the Earth was a lush, green wonderland. This era is often referred to as the “Age of Forests” due to the expansive and dense forests that covered much of the planet. The climate was warm and humid, creating the perfect conditions for plant growth. Gigantic clubmosses, towering tree ferns, and colossal horsetails dominated the landscape, reaching heights of up to 100 feet. These forests were not only visually striking but also played a crucial role in shaping the Earth’s atmosphere by sequestering vast amounts of carbon dioxide.

But here’s where it gets interesting for modern conservation. These ancient forests didn’t just exist in isolation – they created the very air we breathe today. The lesson? Ecosystems don’t just support the species within them; they literally shape the planet’s life-support systems. When we lose a forest today, we’re not just losing trees; we’re potentially altering atmospheric conditions that took millions of years to establish.

Mass Extinctions: Nature’s Ultimate Reality Check

At five other times in the past, rates of extinction have soared. These are called mass extinctions, when huge numbers of species disappear in a relatively short period of time. Paleontologists know about these extinctions from remains of organisms with durable skeletons that fossilized. But these weren’t just random catastrophes – they were the result of specific environmental changes that we can study and learn from.

At least a handful of times in the last 540 million years, 75 to more than 90 percent of all species on Earth have disappeared in a geological blink of an eye in catastrophes we call mass extinctions. Though mass extinctions are deadly events, they open up the planet for new forms of life to emerge. The silver lining here is that life always finds a way to bounce back, but the process takes millions of years – time we simply don’t have in our current crisis.

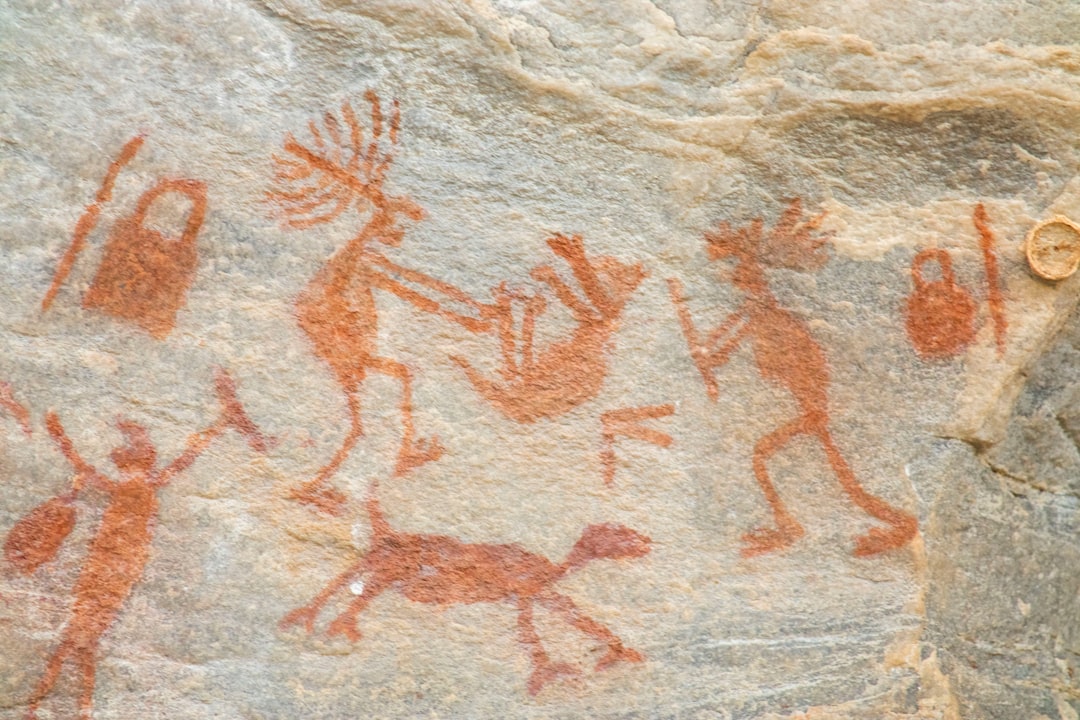

The Human Factor in Prehistoric Extinctions

Here’s something that might surprise you: humans have been changing ecosystems for much longer than we thought. While climate changes were a factor, paleontologists have evidence that overhunting by humans was also to blame. Early humans worked cooperatively to trap and slaughter large animals in pits. About the same time, humans began farming, settling down and making drastic changes in the habitats of other species.

This ancient pattern of human impact teaches us that our species has always been an ecological game-changer. The difference now is the scale and speed of our impact. Understanding how prehistoric human societies affected their environments – sometimes sustainably, sometimes catastrophically – gives us insights into what we’re doing right and wrong today.

Rewilding: Bringing the Past into the Present

One of the most exciting applications of prehistoric ecosystem knowledge is something called Pleistocene rewilding. Pleistocene rewilding is the advocacy of the reintroduction of extant Pleistocene megafauna, or the close ecological equivalents of extinct megafauna. It is an extension of the conservation practice of rewilding, which aims to restore functioning, self-sustaining ecosystems through practices that may include species reintroductions.

The idea isn’t as crazy as it sounds. Research shows that species interactions play a pivotal role in conservation efforts. Communities where species evolved in response to Pleistocene megafauna (but now lack large mammals) may be in danger of collapse. Most living megafauna are threatened or endangered; extant megafauna have a significant impact on the communities they occupy, which supports the idea that communities evolved in response to large mammals. Imagine elephants in America or giant tortoises in places where their ancient relatives once roamed – it’s not science fiction, it’s serious conservation science.

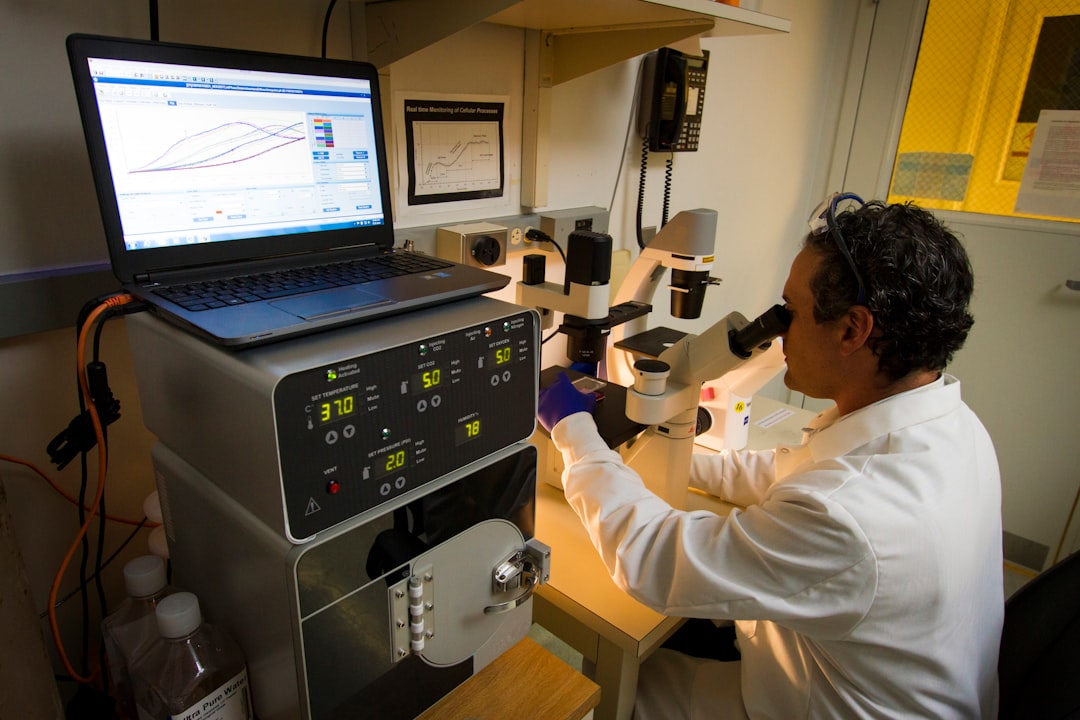

DNA Detective Work: Solving Ancient Mysteries

Modern technology is revolutionizing how we study prehistoric ecosystems. As the power of genetic sequencing technology has advanced, and become both cheaper and faster, researchers have begun to compare the genomes of ancient and museum specimens with those of their living descendants. Scientists are now using historical DNA to establish baselines for assessing how much genetic diversity has been lost over time – an indicator of a population’s health and its ability to adapt to a changing world. They’re using it to identify the genealogical continuity of populations and to make decisions about whether remnant populations should be combined, connected with others, or kept separate.

This genetic archaeology is like having a direct conversation with the past. We can now understand not just what species existed, but how genetically diverse they were, how they moved across landscapes, and what made them successful or vulnerable. It’s giving conservationists tools they never had before to make informed decisions about saving species today.

The Everglades: A Case Study in Historical Restoration

The Everglades wetlands in Florida, which include Everglades National Park (a World Heritage Site), have declined by as much as 50% due to an altered hydrologic regime, and diversions for agriculture and development. Starting in the late 1990s, there has been a broad push to restore this unique ecosystem over the next 30 – 50 years. In the absence of long-term ecological studies, the paleoecological record can be used to understand how the Everglades have responded to past hydrological changes during the last several thousand years and applied to set targets for today’s restoration efforts.

This isn’t just about fixing something that’s broken – it’s about using the past as a blueprint for the future. The Everglades project shows how understanding prehistoric ecosystem dynamics can guide massive restoration efforts. When you know how a system functioned for thousands of years, you have a much better chance of fixing it properly.

Marine Lessons from Ancient Oceans

The ocean’s prehistoric past holds crucial lessons for marine conservation today. In marine settings, changes to species abundances are commonly used to detect the effects of human actions by comparing the living community to the accumulate dead shells in the associated sediments. These “live-dead” comparisons use simple metrics like richness, evenness, taxonomic similarity, and rank-order abundance to determine whether a community has changed. In many cases, changes can be linked to specific human actions, like overfishing or eutrophication (i.e., excessive nutrient input, commonly leading to depletion of oxygen in a body of water), which can in turn inform the conservation measures that would be appropriate to restore the community.

This technique is like having a before-and-after photo that spans thousands of years. Marine conservationists can literally dig into the seafloor and find out what healthy ocean communities looked like before human interference. It’s detective work that’s helping save coral reefs, fisheries, and entire marine ecosystems.

The Sixth Extinction: Learning from Past Crises

We’re currently living through what many scientists call the sixth mass extinction, but understanding the previous five gives us perspective on what we’re facing. The Holocene extinction, also referred to as the Anthropocene extinction or the sixth mass extinction, is an ongoing extinction event caused exclusively by human activities during the Holocene epoch. This extinction event spans numerous families of plants and animals, including mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and invertebrates, impacting both terrestrial and marine species.

But here’s the crucial difference: Because organisms aren’t adapted for very rare global events, survival is more a matter of luck than some innate “superiority”. Dinosaurs survived the mass extinction at the end of the Triassic, but that doesn’t mean they were superior to the animals that went extinct or somehow “deserved” to succeed. Similarly, they went extinct at the end of the Cretaceous (except for a few groups of birds), but that doesn’t mean that mammals are superior. The lesson? Mass extinctions are random disasters, not evolutionary progress. This time, we have the knowledge and potentially the power to prevent one.

Conservation Strategies Born from Ancient Wisdom

Ecological history provides critical baselines for forecasting. Identifying what has been lost due to human activities – from individual species to disturbance regimes to ecosystem functions – establishes restoration targets. Characterizing “slow” ecological processes – those requiring decades to millennia to play out – alerts us to constraints on system evolution. Assessing past environmental and ecological variability allows us to determine risks and thresholds, as well as to develop realistic targets for sustainable management. Diagnosing ecological legacies of past events or regimes yields a better understanding of the current state of modern systems. And historical baselines provide context for evaluating the significance of ongoing or projected change.

This prehistoric knowledge isn’t just academic – it’s a practical toolkit. When we understand how ecosystems naturally fluctuate over thousands of years, we can distinguish between normal variation and genuine crisis. It’s the difference between treating a symptom and curing a disease.

The truth is, every fossil tells a story, and every ancient ecosystem holds lessons that could help us navigate our current environmental crisis. These prehistoric worlds weren’t perfect, but they were functional in ways that sustained life for millions of years. As we face unprecedented challenges, perhaps it’s time we listened more carefully to what the deep past is trying to teach us. After all, our planet has faced extinction crises before and recovered – but this time, we’re both the cause and potentially the solution. What will our legacy be in the fossil record millions of years from now?