The world of Jurassic dinosaurs wasn’t just about massive herbivores peacefully munching on ferns while towering predators roamed unchecked. Recent fossil discoveries are completely rewriting what we thought we knew about these ancient ecosystems. Scientists have uncovered a complex web of interactions that reveals a far more intricate survival story than anyone imagined.

Evidence from fossilized bite marks, trackways, and even preserved stomach contents shows that predator-prey relationships were anything but straightforward. Apex hunters like Allosaurus may have targeted young or vulnerable prey, while heavily armed herbivores such as Stegosaurus and Ankylosaurs weren’t just passive victims—they fought back. Some fossils even suggest cases of scavenging and opportunistic feeding rather than clean predator kills. These insights paint the Jurassic not as a simple battlefield of hunters and hunted, but as a dynamic world where survival hinged on strategy, adaptation, and sometimes sheer luck.

The Great Jurassic Battle Zone: When Predators Met Their Match

Picture this: a fierce Allosaurus charging toward its prey, only to be met with the bone-crushing reality of a Stegosaurus tail spike. In several reports, individuals of the large predator Allosaurus – a theropod dinosaur, like T. rex, that lived 155–145 million years ago – have been found with puncture wounds from encounters with Stegosaurus. Robert Bakker and his colleagues reported an Allosaurus specimen with multiple large wounds through its pelvis, roughly the size of the tail spikes carried by stegosaurs – known popularly as thagomizers.

This Allosaurus was so severely injured that it did not recover and eventually died of its wounds. These findings completely shatter the old notion that predators always had the upper hand. The Jurassic was a battlefield where prey fought back with deadly consequences.

Fossil Evidence That Rewrites Everything We Thought We Knew

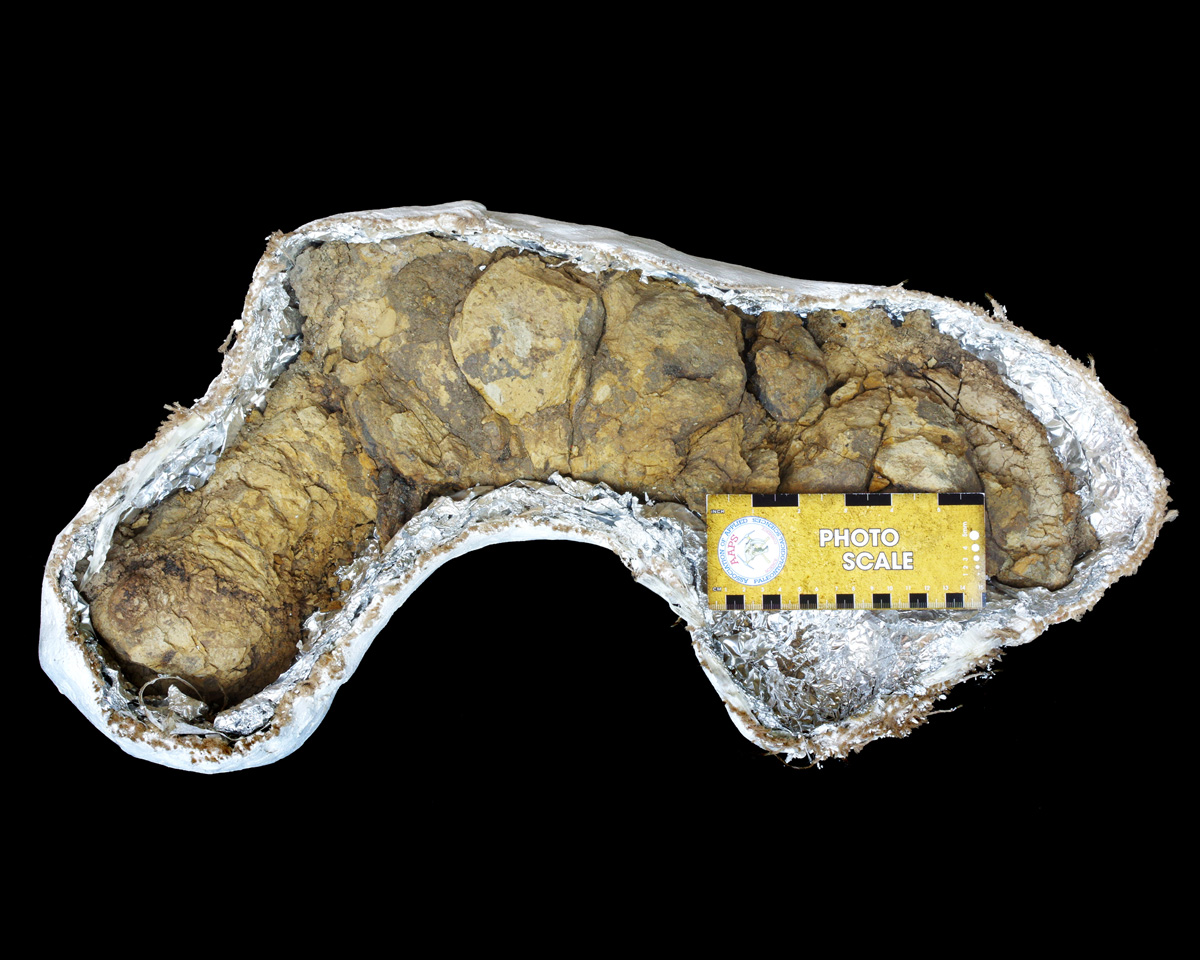

The most groundbreaking discoveries come from analyzing what scientists politely call “bromalites” – basically fossilized poop. Palaeontologists from Uppsala University, in collaboration with researchers from Norway, Poland and Hungary, have examined hundreds of samples using advanced synchrotron imaging to visualise the hidden, internal parts of the fossilised faeces, known as coprolites, in detail. By identifying undigested food remains, plants and prey, they have recreated the structure of the ecosystems at the time when dinosaurs began their success story.

The coprolites contained remains of fish, insects, larger animals and plants, some of which were unusually well preserved, including small beetles and semi-complete fish. Other coprolites contained bones chewed up by predators that, like today’s hyenas, crushed bones to obtain salts and marrow. These preserved remnants are giving us an unprecedented window into who was eating whom millions of years ago.

Allosaurus: The Apex Predator That Wasn’t Quite Apex

Not only is Allosaurus the best represented large theropod dinosaur in the fossil record, it seems to have been ‘the’ predator design of the late Jurassic. But here’s where things get interesting – being the top predator didn’t guarantee survival. Supporting active predation, an Allosaurus tail vertebra shows a healed puncture wound matching a Stegosaurus tail spike, while a Stegosaurus neck bone bears a U-shaped bite mark corresponding to Allosaurus jaws. This evidence suggests Allosaurus actively hunted these well-defended herbivores.

What’s shocking is that roughly one in three fossil bones from certain sites show tooth marks from large carnivores, predominantly Allosaurus. These weren’t just successful hunts – many showed signs of desperate scavenging when fresh kills were scarce.

The Surprising Dietary Secrets of Giant Herbivores

Recent coprolite studies have revealed something absolutely mind-blowing about early sauropods. The contents of coprolites from the first large herbivorous dinosaurs, the long-necked sauropods, surprised the researchers. These contained large quantities of tree ferns, but also other types of plants, and charcoal. The palaeontologists hypothesise that charcoal was ingested to detoxify stomach contents, as ferns can be toxic to herbivores.

Think about that for a second – these massive plant-eaters were basically self-medicating by eating burnt plant material. It’s like discovering ancient dinosaurs had their own version of activated charcoal supplements. This completely changes our understanding of how intelligent these supposedly simple herbivores really were.

Small but Deadly: The Underestimated Hunters

Compsognathus is an interesting predator from the Late Jurassic Era. Its sharp teeth and swift movements made it a formidable predator despite its small size. It was one of the smaller dinosaurs, with an estimated length of about 2 feet and a weight of approximately 2.5-5.5 lbs. This size estimate is based on the well-preserved fossils that have been found, providing a clear picture of the dinosaur’s physical dimensions.

But don’t let the size fool you. These pint-sized predators were lightning-fast killing machines that could dart through dense vegetation, picking off insects, small reptiles, and anything else they could catch. They proved that in the Jurassic, you didn’t need to be massive to be a successful predator.

Pack Hunting: The Game-Changing Strategy

Known for its social behavior, Allosaurus often hunted in packs, employing strategies akin to modern Komodo dragons. This group dynamic allowed them to target vulnerable prey effectively, though their high casualty rates during hunts underline the challenges of predation in this ecosystem.

The fossil evidence for pack hunting is staggering. Multiple Allosaurus specimens found in the same locations, along with coordinated attack patterns preserved in stone, suggest these predators worked together like ancient wolves. However, the high injury rates tell us that even pack hunting was incredibly dangerous in the Jurassic world.

The T-Rex Debate That Shook Paleontology

In the 1990s, dinosaur paleontologist Jack Horner caused a stir in the scientific community by suggesting that T. rex was too slow and clumsy to be an active predator, as it is typically considered. Horner himself has since backtracked, taking the stance now that T. rex was both a predator and scavenger. In all likelihood, this is the correct conclusion.

When examining the skeletons of dinosaurs living at the same time as T. rex, there are more and more cases where T. rex bite marks are being found. In addition to bite marks, T. rex teeth have also been found embedded in the bones of their prey. The evidence is clear – these weren’t just giant vultures, they were active, terrifying hunters.

Marine Predators: The Ocean’s Forgotten Killers

While everyone focuses on land-based dinosaurs, the Jurassic oceans were equally brutal. A new long-necked marine reptile, Plesionectes longicollum, has been identified from a decades-old fossil found in Germany’s Posidonia Shale. The remarkably preserved specimen rewrites part of the Jurassic marine story, revealing unexpected diversity during a time of oceanic chaos.

These marine predators weren’t just swimming around peacefully. Recent fossil evidence shows bite marks on nautilids and other marine creatures that reveal complex predator-prey relationships in ancient seas. The ocean was just as dangerous as the land.

Defensive Evolution: When Prey Fought Back

Many dinosaur species like Triceratops, Ankylosaurus, and Stegosaurus protected themselves from their predators with defensive horns, plates, spikes, and clubs. Among herbivorous dinosaurs, Kentrosaurus stands out as a living fortress, covered in a formidable array of spikes that ran down its tail, making it nearly untouchable from behind. Unlike its larger relative Stegosaurus, this smaller stegosaur had a more balanced build, with its center of mass positioned forward of the hips, allowing it to pivot quickly – an ability that would have made it a nightmare for any predator trying to get close. Its tail was an exceptionally flexible weapon, lined with long, sharp spikes that could swing with lethal force, potentially breaking bones or impaling attackers

The arms race between predator and prey drove some of the most incredible evolutionary innovations we’ve ever seen. These weren’t passive victims – they were walking weapons platforms designed specifically to kill anything that tried to eat them.

The Latest Scientific Breakthroughs

Recent studies of dinosaur tracks from Middle Jurassic formations in Denmark and Iran have provided evidence of diverse dinosaur faunas, including sauropod tracks and ornithischian trackways from various formations.

Recent research is revealing trackways and fossil sites that show unprecedented diversity in Jurassic ecosystems. Scientists are discovering that predator-prey dynamics were far more complex than previously imagined, with evidence of coordinated hunting, defensive herding, and sophisticated behavioral adaptations.

Conclusion: The Real Jurassic Was Far More Complex

The picture emerging from modern paleontology is absolutely fascinating. The Jurassic wasn’t simply about big predators eating smaller prey – it was an intricate ecosystem where survival required intelligence, cooperation, and constant adaptation. The research addresses a significant gap in current knowledge: the early phases of dinosaur evolution during the Late Triassic period. Although much is known about their lives and extinction, the ecological and evolutionary processes that led to their rise are largely unexplored.

Every new fossil discovery reveals more complexity in these ancient food webs. From charcoal-eating sauropods to pack-hunting Allosaurus, from spike-wielding Stegosaurus to lightning-fast Compsognathus, the Jurassic was a world where every creature was locked in an evolutionary arms race for survival. The hunters weren’t always the ones who came out on top – and that’s what makes this ancient world so incredibly captivating.

Who would have thought that fossilized dinosaur droppings would hold the keys to understanding one of Earth’s most fascinating periods? Sometimes the most important discoveries come from the most unexpected places.