Picture a world where colossal marine reptiles the size of modern whales cruised through warm, shallow seas that split entire continents in half. This wasn’t science fiction – this was reality roughly eighty million years ago, during the Late Cretaceous period, when Earth’s oceans belonged to the mosasaurs. With double-hinged jaws, sharp conical teeth, and bodies built for speed, mosasaurs were the undisputed apex predators of their time. They hunted everything from fish and turtles to other marine reptiles, dominating ecosystems with ruthless efficiency. Fossil evidence shows they could adapt to different environments, spreading across oceans worldwide. Some species even reached lengths of over fifty feet, rivaling today’s largest predators. These “underwater dragons” weren’t just survivors of their age—they were the rulers of an ocean kingdom teeming with danger and drama.

The Rise of the Ocean’s Ultimate Predators

When we think about apex predators, our minds usually jump to great white sharks or killer whales. But long before these modern hunters evolved, there were creatures that made them look tame by comparison. During the last 25 million years of the Cretaceous period (Turonian–Maastrichtian ages), with the extinction of the ichthyosaurs and pliosaurs, mosasaurids became the dominant marine predators. These weren’t just another group of ancient reptiles – they were evolutionary masterpieces that transformed from land-dwelling lizards into ocean-ruling titans in remarkably short geological time.

The story of how mosasaurs seized control of ancient seas reads like a tale of opportunistic conquest. About 93-94 million years ago, an extinction event occurred that was caused by large-scale underwater volcanic activity. It wiped out several groups of animals in the seas, among these were the ichthyosaurs or “fish lizards”, and the pliosaurs, large-headed and more predatory cousins of the plesiosaurs. With their competition eliminated, mosasaurs stepped into the vacant throne of marine supremacy.

From Lizards to Leviathans

The transformation of mosasaurs from terrestrial reptiles to marine giants represents one of evolution’s most dramatic makeovers. The modern relatives of mosasaurs are snakes and monitor lizards, both of which live on land. Imagine a Komodo dragon, but instead of hunting on Indonesian islands, it decided to conquer the open ocean – and succeeded spectacularly.

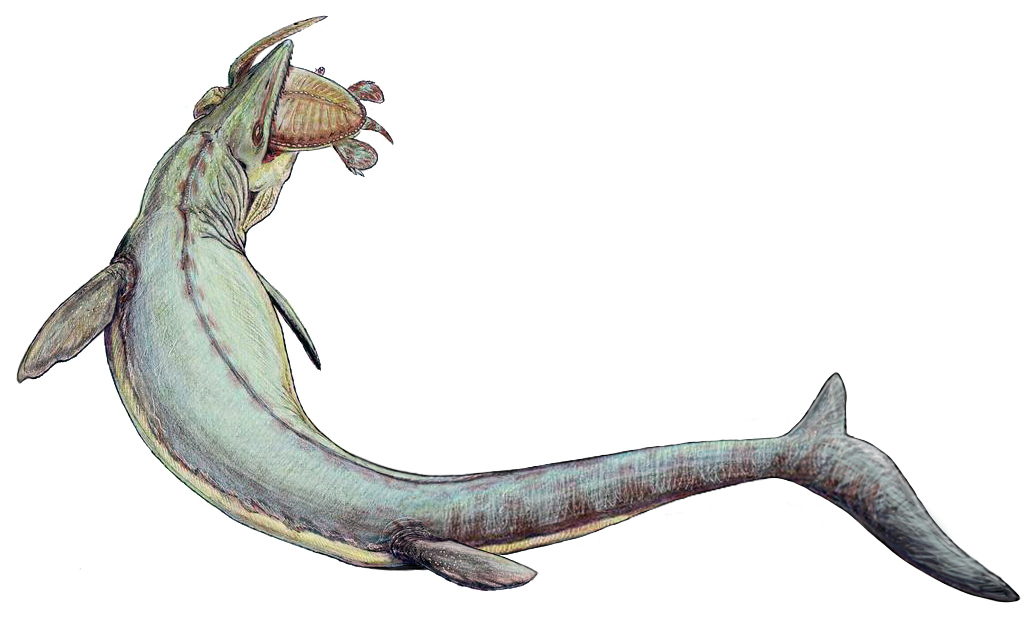

During the middle of the Cretaceous Period, about 98 million years ago, a family of lizards related to modern monitors called the aigialosaurs began returning to the oceans. This wasn’t just a simple lifestyle change; it was an evolutionary revolution that required massive anatomical restructuring. Their limbs became paddle-shaped flippers, their tails developed powerful swimming muscles, and their entire body plan shifted to accommodate an aquatic existence.

Anatomical Marvels Built for Destruction

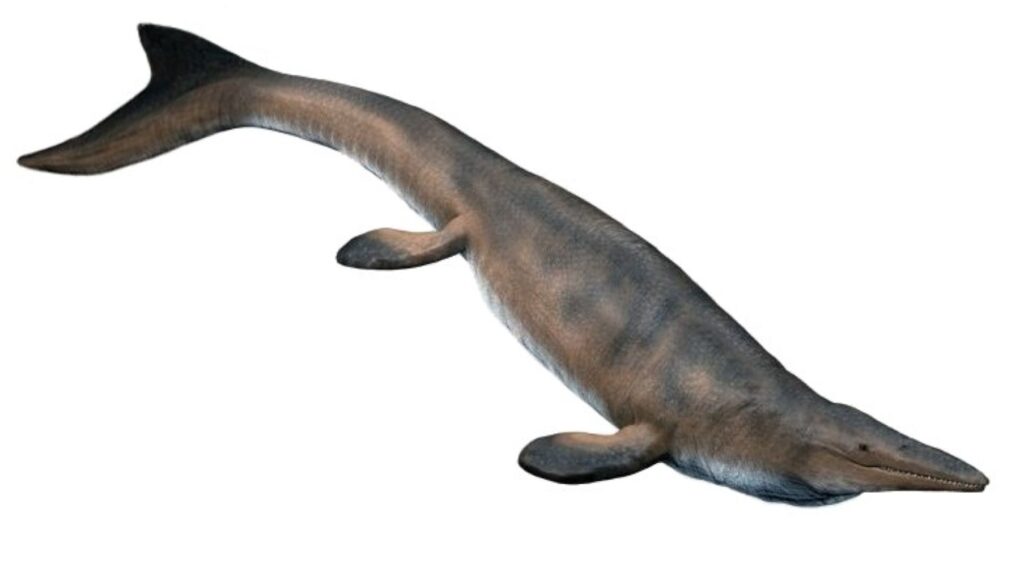

Mosasaurs had a body shape similar to that of modern-day monitor lizards (varanids), but were more elongated and streamlined for swimming. However, calling them “swimming lizards” would be like describing a Formula One car as a “fast horse and buggy” – technically accurate but missing the revolutionary engineering involved.

Mosasaurs had double-hinged jaws and flexible skulls (much like those of snakes), which enabled them to gulp down their prey almost whole. Their jaws could unhinge like a snake’s, allowing them to swallow prey that would seem impossibly large. Similar to snakes, Mosasaurs had jaws could expand to help swallow large whole prey. Also, like a snake, mosasaurs had two sets of teeth in their upper jaws. This wasn’t just adaptation – it was over-engineering for maximum lethality.

The Incredible Diversity of Deadly Designs

Not all mosasaurs were created equal, and their diversity was staggering. The smallest-known mosasaur was Dallasaurus turneri, which was less than 1 m (3.3 ft) long. Larger mosasaurs were more typical, with many species growing longer than 4 m (13 ft). At the other extreme, some species achieved truly monstrous proportions that would make modern marine predators seem like minnows.

At the end of the Cretaceous, there were several types of mosasaurs with rounded teeth for crushing shells, as well as lithely-built, fast-swimming pursuit predators that hunted fish in open water. Then there were whale-sized ambush predators, like Mosasaurus itself, with jaws built for both crushing and cutting up its victims. This specialization allowed different mosasaur species to exploit various ecological niches, preventing competition and maximizing their collective dominance over marine ecosystems.

Swimming Machines with Shark-Like Power

For decades, scientists thought mosasaurs swam like giant sea snakes, undulating their entire bodies through the water. Recent discoveries shattered this assumption and revealed something far more impressive. New evidence suggests that many advanced mosasaurs had large, crescent-shaped flukes on the ends of their tails, similar to those of sharks and some ichthyosaurs. Rather than use snake-like undulations, their bodies probably remained stiff to reduce drag through the water, while their tails provided strong propulsion.

This discovery transformed our understanding of mosasaur hunting strategies. These animals may have lurked and pounced rapidly and powerfully on passing prey, rather than chasing after it. Picture a fifty-foot ambush predator with the explosive power of a great white shark – that’s what late Cretaceous seas contained, and there were multiple species of them sharing the same waters.

The Western Interior Seaway: Mosasaur Paradise

The Western Interior Seaway (also called the Cretaceous Seaway, the Niobraran Sea, the North American Inland Sea, or the Western Interior Sea) was a large inland sea that existed roughly over the present-day Great Plains of North America, splitting the continent into two landmasses, Laramidia to the west and Appalachia to the east. The ancient sea, which existed for 34 million years from the early Late Cretaceous (100 Ma) to the earliest Paleocene (66 Ma), connected the Gulf of Mexico (then a marginal sea of the Central American Seaway) to the Arctic Ocean. At its largest extent, the seaway was 2,500 ft (760 m) deep, 600 mi (970 km) wide and over 2,000 mi (3,200 km) long.

This wasn’t just any body of water – it was mosasaur heaven. The waters of the WIS were warm, shallow, and inhabited by a plethora of marine animals. Other marine life included sharks such as Squalicorax, Cretoxyrhina, and the giant durophagous Ptychodus mortoni (believed to be 10 metres (33 ft) long); and advanced bony fish including Pachyrhizodus, Enchodus, and the massive 4-to-5-metre (13 to 16 ft) long Xiphactinus, larger than any modern bony fish. Other sea life included invertebrates such as mollusks, ammonites, squid-like belemnites, and plankton including coccolithophores that secreted the chalky platelets that give the Cretaceous its name, foraminiferans and radiolarians. For mosasaurs, this represented an endless buffet of prey options.

Feeding Habits That Redefined Apex Predation

Mosasaurs weren’t picky eaters – they were oceanic vacuum cleaners with attitude. Paleontologists have discovered the preserved remains of mosasaur stomachs which contain food like fish, sharks, cephalopods, birds, and even other mosasaurs. It’s likely that mosasaurs weren’t picky and would eat pretty much anything which could fit into their enormous mouths – which, it turns out, was a lot. Their dietary flexibility was both a strength and a testament to their dominance.

What makes their feeding behavior even more remarkable is the evidence of cannibalism. There’s not much that could have preyed upon this gigantic creature, but bite marks and mangled paddles of fossil mosasaurs suggest that mosasaurs often fought (and ate) each other. This wasn’t desperate hunger – it was the behavior of an apex predator so dominant that the only thing dangerous enough to hunt a mosasaur was another, larger mosasaur.

Revolutionary Breathing and Reproduction

Unlike modern marine mammals that evolved complex diving adaptations over millions of years, mosasaurs had to solve the breathing problem quickly. Although mosasaurs were aquatic, they were reptiles, which means they had to surface to breathe air, like a sea turtle today. Yet somehow, they managed to become the ocean’s most successful predators despite this apparent limitation.

Perhaps even more impressive was their reproductive strategy. Mosasaurs likely gave birth to live young. Scientists reached this conclusion when a mosasaur skeleton containing five unborn young in its abdomen was discovered in South Dakota. The maximum number of young in one birth was likely around four or five. The discovery of several specimens of juvenile and neonate-sized mosasaurs unearthed more than a century ago indicate that mosasaurs gave birth to live young, and that they spent their early years of life out in the open ocean, not in sheltered nurseries or areas such as shallow water as previously believed. This meant baby mosasaurs were born directly into the most dangerous environment on Earth and had to survive from day one.

The Skin and Scales of Sea Monsters

Recent discoveries have revealed fascinating details about mosasaur appearance that make them even more incredible than previously imagined. Material from Jordan has shown that the bodies of mosasaurs, as well as the membranes between their fingers and toes, were covered with small, overlapping, diamond-shaped scales resembling those of snakes. Much like those of modern reptiles, mosasaur scales varied across the body in type and size. In Harrana specimens, two types of scales were observed on a single specimen: keeled scales covering the upper regions of the body and smooth scales covering the lower.

The coloration was equally impressive. The discovery is melanin in mosasaur scales. Like a great white shark, the mosasaurs were two colors. They had a black back and a white belly. This countershading wasn’t just for looks – it was sophisticated camouflage that made these massive predators nearly invisible to prey swimming below them, seeing only the white belly against the bright surface, or to predators above, seeing the dark back against the ocean depths.

The End of an Empire

For roughly twenty-five million years, mosasaurs ruled the oceans with uncontested authority. They themselves became extinct as a result of the K-Pg event at the end of the Cretaceous period, about 66 million years ago. Despite its immense power, the Mosasaur’s reign came to an abrupt end around 66 million years ago during the Cretaceous Paleogene extinction event. This mass extinction, triggered by a combination of volcanic activity and an asteroid impact, wiped out nearly 75% of Earth’s species, including the dinosaurs, marine reptiles, and a majority of marine ecosystems.

The rich marine ecosystems that mosasaurs inhabited and depended upon for food collapsed after the asteroid strike, according to a 2005 study in the Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. This collapse caused all mosasaurs to die out, never to return. The very productivity and diversity that had allowed mosasaurs to thrive became their downfall when the global ecosystem collapsed almost overnight.

Legacy of the Ocean’s Greatest Predators

The extinction of mosasaurs left a void in marine ecosystems that has never been fully filled. After mosasaurs disappeared, crocodilians increased in numbers and took over the role of large marine predators, according to the Netherlands Journal of Geosciences study. However, no marine reptile has since achieved the size, diversity, and global dominance that mosasaurs maintained for millions of years.

Today, paleontologists continue to uncover new mosasaur species and refine our understanding of these remarkable creatures. Each fossil discovery reveals new aspects of their biology, behavior, and evolutionary success. From their revolutionary body plan to their sophisticated hunting strategies, mosasaurs represent one of evolution’s most successful experiments in marine predation. They remind us that the ancient oceans were far more dangerous and dynamic than anything we see today, ruled by creatures that make modern apex predators look almost tame by comparison.

What strikes me most about mosasaurs isn’t just their size or their fearsome appearance – it’s how quickly they evolved from modest land lizards into the ocean’s undisputed rulers. In the grand timeline of life on Earth, twenty-five million years is practically a sprint, yet in that brief window, mosasaurs achieved something no marine reptile has accomplished before or since. They didn’t just adapt to ocean life; they redefined what it meant to be a marine apex predator. Makes you wonder what other evolutionary revolutions might be possible given the right circumstances, doesn’t it?