Dr. Catherine “Cathy” Forster stands as one of the most influential paleontologists of our time, specializing in the evolutionary connections between dinosaurs and birds. Through her groundbreaking fieldwork in Madagascar and comprehensive analysis of theropod dinosaurs, she has transformed our understanding of avian evolution. As one of the foremost female scientists in paleontology, Forster’s meticulous research has illuminated crucial transitional fossils that demonstrate how feathered dinosaurs evolved into the birds we know today. Her story combines scientific excellence with perseverance, showing how determination and innovative thinking can unlock some of Earth’s most fascinating evolutionary mysteries.

Early Life and Educational Journey

Catherine Forster was born in the early 1950s in the United States, growing up during a time when women were significantly underrepresented in scientific fields. From an early age, she displayed a natural curiosity about the prehistoric world, collecting fossils and studying natural history whenever possible. Her formal academic journey began at Minnesota State University, where she initially focused on biology and geology, building a foundation that would later prove invaluable to her specialized work. Unlike many in her field, Forster didn’t pursue paleontology until relatively later in her academic career, completing her doctoral studies at Pennsylvania State University in the late 1980s. This unconventional path gave her a unique interdisciplinary perspective that would later inform her revolutionary approaches to understanding dinosaur-bird connections.

Pioneering Work in Madagascar

Forster made her most significant mark in paleontology through her extensive fieldwork in Madagascar, an island nation off Africa’s southeastern coast known for its unique and isolated fossil record. Beginning in the 1990s, she led multiple expeditions to the Mahajanga Basin, an area rich in Late Cretaceous fossils from approximately 70 million years ago. Her team’s discoveries in Madagascar include several previously unknown species that filled crucial gaps in our understanding of dinosaur evolution. Perhaps most notably, Forster co-discovered and named Rahonavis ostromi, a crow-sized creature that displayed both dinosaurian and avian characteristics, making it a pivotal transitional fossil. The Madagascar expeditions were particularly challenging due to the remote locations, difficult terrain, and limited resources, yet Forster’s determination and expertise resulted in finding some of the most scientifically valuable specimens of the late 20th century.

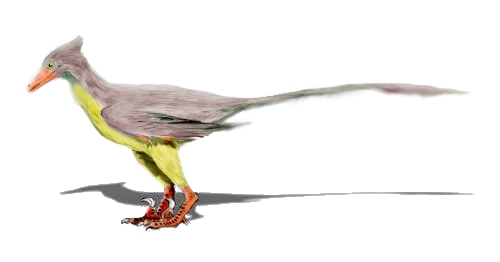

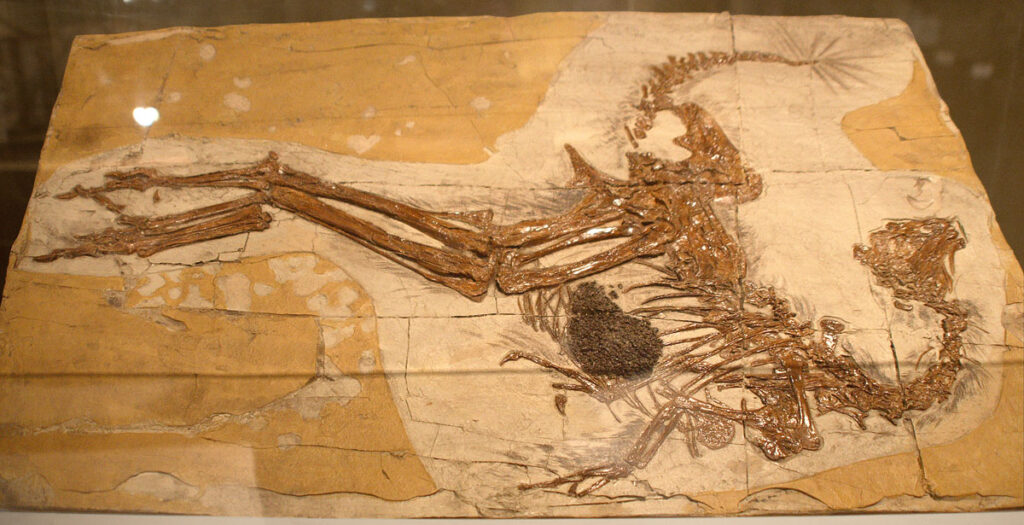

The Discovery of Rahonavis

The discovery of Rahonavis ostromi in 1995 represents one of Forster’s most significant contributions to paleontology. While exploring the Maevarano Formation in northwestern Madagascar, Forster and her team uncovered the partial skeleton of a small, bird-like dinosaur that would prove immensely valuable to understanding avian evolution. Named Rahonavis, meaning “menacing bird” in a combination of Malagasy and Latin, this specimen exhibited an intriguing combination of features. It possessed the long, bony tail and grasping hands typical of dromaeosaurid dinosaurs (relatives of Velociraptor), while simultaneously showing unmistakable bird-like features including well-developed forelimbs with quill knobs – direct evidence of flight feathers. The specimen’s forearms even contained the same bone structure needed for the powerful flight stroke used by modern birds. Forster’s careful analysis of this 70-million-year-old creature provided compelling evidence for the evolutionary link between dinosaurs and birds, supporting the increasingly accepted theory that birds evolved from small, feathered theropod dinosaurs.

Contributions to Theropod Research

Beyond her work with Rahonavis, Forster has made numerous contributions to our understanding of theropod dinosaurs, the group from which birds evolved. She has published extensively on the anatomy, evolutionary relationships, and behaviors of various theropod species, particularly focusing on maniraptoran theropods—the group most closely related to birds. Her research has helped clarify the developmental pathways through which dinosaurian features gradually transformed into avian characteristics over millions of years. Forster’s comparative anatomical studies between modern birds and their dinosaurian ancestors have been particularly valuable, as she meticulously documented the progressive changes in skeletal structure, from the reduction of the long bony tail to the development of a keeled sternum for flight muscle attachment. Additionally, her work on theropod diversity in the southern hemisphere has challenged northern-hemisphere-centric views of dinosaur evolution, revealing distinct evolutionary patterns that enriched our global understanding of dinosaur adaptation and speciation.

Collaborative Research and Academic Partnerships

Throughout her career, Forster has demonstrated remarkable skill in building productive scientific collaborations across institutional and international boundaries. Her partnership with famed paleontologist Dr. David Krause was particularly fruitful, resulting in numerous joint expeditions to Madagascar and subsequent publications that redefined our understanding of Late Cretaceous fauna. Forster has also collaborated extensively with researchers from the Malagasy scientific community, helping to build paleontological expertise within the country and ensuring that Madagascar’s fossil heritage benefits local scientists and institutions. Her inclusive approach extended to working with specialists in avian anatomy, developmental biology, and genetics to build a comprehensive, multidisciplinary understanding of the dinosaur-bird transition. These collaborative efforts have not only enhanced the quality and breadth of her research but have also helped establish international networks of scientific cooperation that continue to advance paleontological knowledge worldwide.

Academic Career and Institution Building

Forster has spent much of her academic career at George Washington University, where she has served as a professor of biology and an integral member of the university’s Center for the Advanced Study of Human Paleobiology. In this capacity, she has mentored numerous graduate students who have gone on to make their contributions to paleontology, creating a lasting legacy that extends beyond her research. Beyond her university responsibilities, Forster has played a key role in building research programs and fossil collections at various institutions. She has been instrumental in developing protocols for the ethical collection, conservation, and repatriation of fossils, ensuring that specimens remain accessible to researchers while respecting the countries of origin. Her institutional contributions extend to museum development, where she has helped design exhibits that effectively communicate the complex story of avian evolution to the general public, making cutting-edge paleontological concepts accessible to non-scientists.

The Feathered Dinosaur Revolution

Forster’s career coincided with and significantly contributed to what paleontologists call the “Feathered Dinosaur Revolution”—a complete transformation in how we understand dinosaurs and their relationship to birds. When she began her career, the theory that birds evolved from dinosaurs, while gaining support, still faced considerable skepticism within parts of the scientific community. Through her research on specimens like Rahonavis and her analysis of other feathered dinosaur fossils, primarily from China, Forster helped solidify the evidence for the dinosaurian origin of birds. She particularly focused on integrating multiple lines of evidence, from skeletal anatomy to feather structure, demonstrating how the classic dinosaurian body plan gradually acquired avian characteristics. Her publications carefully documented the evolutionary sequence from terrestrial theropods to flying birds, identifying the specific adaptations that eventually enabled powered flight. This body of work has been fundamental in establishing what is now the scientific consensus: that birds are, in fact, highly specialized theropod dinosaurs that have survived to the present day.

Challenges as a Woman in Paleontology

Like many female scientists of her generation, Forster navigated significant gender-based obstacles throughout her career in the male-dominated field of paleontology. During her formative years, women were often discouraged from pursuing careers in fieldwork-intensive sciences, with limited access to research opportunities and funding. The physical demands of paleontological expeditions, particularly to remote locations like Madagascar, were frequently cited as reasons why women weren’t “suited” for such work—a notion Forster thoroughly disproved through her successful leadership of numerous challenging field seasons. Beyond the physical aspects, she faced the more subtle challenges of having her ideas taken seriously in academic settings and receiving appropriate credit for her discoveries. Despite these hurdles, Forster persisted, not only establishing herself as a preeminent researcher but also helping to transform paleontology into a more inclusive field. Her success has inspired subsequent generations of female paleontologists, demonstrating that determination and scientific excellence can overcome institutional and cultural barriers.

Public Engagement and Science Communication

Beyond her academic contributions, Forster has dedicated significant energy to communicating paleontological findings to the general public. She has served as a scientific consultant for museum exhibits, documentary films, and popular science publications, helping translate complex evolutionary concepts into accessible formats. Her ability to explain the significance of transitional fossils has been particularly valuable in countering misunderstandings about evolutionary processes. Forster regularly participates in public lectures and educational outreach programs, especially those aimed at encouraging young women to pursue careers in science. Her approach to science communication emphasizes the detective-like nature of paleontology, showing how researchers piece together evidence from fragmentary remains to reconstruct the story of life’s history. Through these efforts, she has helped build public support for paleontological research and conservation, highlighting the importance of understanding our planet’s biological past in the context of modern conservation challenges.

The “Tinamou Problem” and Flight Origins

One of Forster’s more nuanced contributions involves addressing what paleontologists call the “Tinamou Problem”—the question of how flight evolved multiple times or was lost in certain bird lineages. Tinamous are ground-dwelling birds from Central and South America that can fly but rarely do so, raising questions about the evolutionary pathways between non-flying and flying states. Forster applied her extensive knowledge of the dinosaur-bird transition to examine this modern example, looking for clues about how flight capabilities might evolve, become reduced, or be lost entirely. Her comparative studies between fossil specimens like Rahonavis and modern birds with limited flight capabilities helped clarify the anatomical and behavioral steps involved in flight evolution. This research has broader implications for understanding evolutionary processes, particularly how complex adaptations can emerge gradually through natural selection acting on structures that originally served different functions. Through this work, Forster demonstrated how studying living animals can inform our interpretation of fossil evidence, creating a more complete picture of evolutionary history.

Technological Innovation in Fossil Analysis

Throughout her career, Forster has embraced technological innovations that enhance the scientific value of fossil specimens. She was among the early adopters of CT scanning technology in paleontology, using it to examine the internal structures of fossils without damaging them. This approach proved particularly valuable for studying the delicate, hollow bones characteristic of both birds and their dinosaurian ancestors. Forster also pioneered the application of 3D modeling and comparative morphometrics to quantitatively analyze subtle evolutionary changes in skeletal structure across the dinosaur-bird transition. More recently, she has incorporated insights from developmental biology and genetics into her paleontological research, examining how changes in growth patterns and gene expression might explain the evolutionary modifications visible in the fossil record. This integration of cutting-edge technology with traditional paleontological methods has significantly enhanced the precision and scope of her research, allowing for more robust testing of hypotheses about avian evolution.

Legacy and Ongoing Influence

As Forster continues her research career, her legacy already stands as one of transformative impact on paleontology and evolutionary biology. The specimens she has discovered and described form crucial pieces in our understanding of the dinosaur-bird evolutionary puzzle. Her methodological innovations, particularly in integrating multiple scientific disciplines to address paleontological questions, have influenced research practices throughout the field. Perhaps most significantly, her success as a female scientist in a traditionally male-dominated discipline has helped reshape the demographics and culture of paleontology. The students she has mentored—many of them women and individuals from underrepresented groups—continue to expand on her work, ensuring that her scientific approach and inclusive values persist in the next generation of researchers. Forster’s career demonstrates how individual scientists can not only advance specific knowledge within their field but also transform the very nature of scientific practice through their example and leadership.

Current Research and Future Directions

Even after decades of groundbreaking work, Forster continues to actively contribute to paleontological research, focusing on several promising areas that build upon her previous discoveries. She remains involved with ongoing excavations in Madagascar, where new fossil sites continue to yield specimens that illuminate the unique evolutionary history of the island’s fauna. Additionally, Forster has expanded her research focus to include the broader ecological context of dinosaur-bird evolution, examining how environmental changes and ecosystem interactions might have influenced the development of flight. She has also turned attention to applying new analytical techniques to previously discovered specimens, extracting additional information through advanced imaging technologies and biochemical analyses that weren’t available when the fossils were first found. Looking toward the future, Forster has expressed particular interest in integrating paleontological evidence with insights from genomics and developmental biology, creating a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying major evolutionary transitions. Through this continued work, she demonstrates the dynamic, ever-evolving nature of scientific research and the inexhaustible questions that remain about our planet’s fascinating biological history.

Conclusion

Dr. Cathy Forster’s remarkable career stands as testimony to the power of scientific curiosity, methodological innovation, and perseverance in the face of challenges. Her discoveries in Madagascar, particularly Rahonavis, have provided critical evidence for understanding how dinosaurs evolved into birds, one of evolution’s most fascinating transitions. Beyond her specific findings, Forster’s collaborative approach and commitment to mentoring have strengthened the entire field of paleontology, making it more inclusive and methodologically robust. As we continue to uncover Earth’s prehistoric past, Forster’s work reminds us that the greatest scientific advances often come from questioning established perspectives and meticulously examining the evidence, regardless of how fragmentary it might initially appear. Through her research, teaching, and public outreach, she has not only illuminated the origins of flight but also demonstrated the soaring potential of dedicated scientific inquiry.