Picture this: sixty-six million years ago, massive beasts roamed the Earth like something out of a fantasy movie. Tyrannosaurus rex terrorized the landscape while herds of Triceratops grazed peacefully nearby. Then suddenly, everything changed. But what if the story you’ve heard about their extinction is missing a crucial chapter? Long before the asteroid struck, Earth’s climate was already shifting in dramatic ways. Evidence from fossils and rock layers shows rising volcanism, fluctuating sea levels, and temperature swings that stressed ecosystems worldwide. Plant communities struggled, food chains grew fragile, and some dinosaur populations may have been declining even before the final blow. These clues suggest the asteroid wasn’t the only villain of the story—it may have been the last strike in a world already on the edge. Could climate chaos have been softening the ground for extinction all along?

The Asteroid That Stole the Show

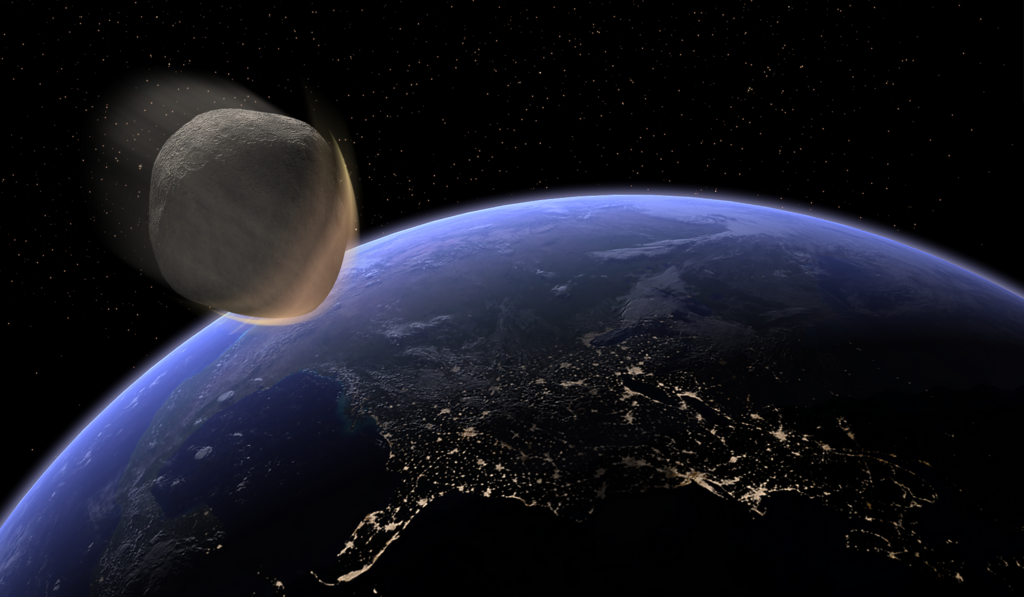

For decades, science textbooks have told us the same story about dinosaur extinction. A massive asteroid, roughly ten kilometers in diameter, slammed into the Yucatán Peninsula 66 million years ago, causing devastation and climate disruption that led to a mass extinction of roughly three-quarters of plant and animal species on Earth. The Chicxulub crater stands as proof of this cosmic collision, stretching approximately 150 kilometers across the Mexican landscape.

The impact created an abrupt global catastrophe where fine dust suspended in the atmosphere blocked sunlight, decreasing or stopping photosynthesis entirely. This ecological disaster seemed like the perfect explanation for why the mighty dinosaurs vanished so completely. But recent discoveries suggest this might only be half the story.

The Troubling Signs Before Impact

Scientists have uncovered disturbing evidence that suggests dinosaurs were already in serious trouble before any space rock arrived. Research shows that dinosaur diversification shifted to a declining pattern roughly 76 million years ago, with extinction risk related to species age during the decline, suggesting a lack of evolutionary novelty or adaptation to changing environments.

Think of it like watching a magnificent old tree slowly dying from disease, only to have lightning strike it down before it could recover. Studies indicate dinosaurs were already in decline for 10 million years before the asteroid impact, with changing climate and vegetation causing chaos in the complicated and sensitive food web. This paints a much more complex picture than the simple “asteroid killed everything” narrative we’re used to hearing.

When the Earth Started Cooling Down

The Late Cretaceous period was like Earth’s tropical paradise, but this comfortable greenhouse world was gradually coming to an end. Peak warmth was reached during the Cenomanian-Turonian period with sea-surface temperatures reaching at least 30°C in tropical areas, but after this interval, temperatures decreased significantly during the Campanian-Maastrichtian period.

This cooling was substantial, with temperatures dropping roughly 7°C in the North Atlantic and 10°C in southern latitudes, intensifying during the Maastrichtian until the extinction event. For creatures that had thrived in a warm, stable climate for millions of years, this change was like turning down the thermostat in their global home. The cooling wasn’t just uncomfortable – it was potentially lethal for animals whose biology depended on consistent warmth.

The Volcanic Nightmare in India

While the climate was cooling, another disaster was brewing on the other side of the world. The Deccan Traps in western India began erupting around 66 million years ago, creating volcanic layers more than two kilometers thick in some areas, making this the second-largest volcanic eruption ever recorded on land.

These volcanic eruptions spewed enormous amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, causing greenhouse warming, while also releasing toxic gases like sulfur and chlorine, resulting in acid rain that further damaged the global environment. The sulfurous gases could cool the atmosphere short-term while carbon dioxide warmed it long-term, leading to climate swings between warm and cold periods that made survival extremely difficult for life on Earth. Imagine trying to adapt to weather that constantly shifted between scorching heat and freezing cold.

The Herbivore Crisis That Shook Everything

One of the most fascinating discoveries involves what happened to plant-eating dinosaurs before the extinction. Research indicates that the decline of dinosaurs was driven by global climate cooling and a significant drop in herbivorous diversity, likely because hadrosaurs were outcompeting other herbivorous species.

This created a domino effect throughout the entire ecosystem. When one group of herbivores becomes too dominant, it’s like having only one type of restaurant in a city – everything becomes unbalanced. Large herbivores like ankylosaurs, ceratopsians, and hadrosaurs were highly influential in Late Cretaceous ecosystems because they had numerous connections in the food web, serving as prey for different predators depending on their life stages. When this system became unstable, the entire food chain suffered.

Temperature-Dependent Troubles

Here’s where the story gets really interesting from a biological perspective. Dinosaurs were likely mesothermic organisms with varying temperature regulation abilities, and their activities were probably partially constrained by environmental temperatures, especially larger dinosaurs who relied substantially on mass homeothermy to maintain constant body temperatures.

Scientists have proposed that if sex determination in dinosaurs was temperature dependent, like in modern crocodiles and turtles, sex switching of embryos could have contributed to diversity loss as the global climate cooled at the end of the Cretaceous. Picture entire populations unable to produce balanced numbers of male and female offspring simply because the temperature dropped a few degrees. This would have been a slow-motion disaster unfolding over thousands of years.

The Marine World Was Suffering Too

The problems weren’t limited to land-dwelling dinosaurs. Evidence from Tunisia shows that marine life was negatively affected by increased warmth and humidity linked to intense Deccan Traps activity, with marine extinctions beginning before the asteroid impact, and similar patterns observed in China’s Songliao Basin.

Ocean ecosystems were experiencing their own crisis as temperatures fluctuated wildly. Temperature increased about three to four degrees rapidly between 65.4 and 65.2 million years ago, while water temperature decreased, causing a drastic decrease in marine diversity. The seas that had supported diverse life for millions of years were becoming increasingly hostile environments.

The Debate Among Scientists

Not all researchers agree on how much climate change contributed to dinosaur extinction. Some studies demonstrate that even without other effects, an impact winter would have led to dinosaur extinction, while suggesting that the impact winter represented a climatological threshold necessary to trigger complete extinction of non-avian dinosaurs.

However, others argue for a more complex scenario. Some research suggests volcanic eruptions could have injected massive amounts of greenhouse gases and particles into the atmosphere, stressing late Cretaceous life, followed by the impact’s nuclear winter that sharply cooled Earth and caused ecosystem collapse. It’s like arguing whether a weakened patient died from the disease or the final blow – both factors likely played important roles.

Evidence From Around the World

Global evidence supports the idea that dinosaurs were struggling before the asteroid impact. In China’s Shanyang Basin, as precipitation and temperature increased, dinosaur fossil abundance gradually declined, with no dinosaur fossils discovered during the last 0.4 million years of the Cretaceous period.

The latest Cretaceous period of North America provides the best fossil record to examine this debate, though even here diversity reconstructions are complicated by uneven sampling biases. Scientists are working with incomplete puzzle pieces, but the emerging picture consistently shows ecosystems under stress long before the final catastrophe arrived.

The Final Catastrophic Blow

While climate change was weakening dinosaur populations, the asteroid impact delivered the killing blow. The impact vaporized sulfur-rich rock and injected it into the atmosphere, leading to sudden catastrophic effects on climate worldwide, causing large temperature drops and devastating the food chain.

The impact created an “impact winter” by ejecting immense quantities of dust and aerosols into the atmosphere, blocking sunlight for years, causing global temperatures to plummet and halting photosynthesis. For ecosystems already stressed by millions of years of climate change, this was the final straw that broke the camel’s back.

Conclusion: A Perfect Storm of Disasters

The extinction of dinosaurs wasn’t a simple story of cosmic bad luck. Instead, it appears to have been a perfect storm of environmental disasters that unfolded over millions of years. Climate cooling, volcanic eruptions, ecosystem disruption, and changing vegetation patterns had already pushed dinosaur populations to the brink. The asteroid impact simply finished what climate change had started.

This revelation changes how we think about mass extinctions and the resilience of life on Earth. It suggests that even the most dominant creatures can be vulnerable to gradual environmental changes, making them sitting ducks for sudden catastrophes. The dinosaurs’ story serves as a sobering reminder that in nature, it’s often not the biggest disaster that kills you – it’s the slow accumulation of smaller stresses that leaves you unable to survive when the final blow arrives.

What other “sudden” disasters in Earth’s history might actually have deeper, slower-burning causes we haven’t discovered yet?