Ever wonder whether the mighty dinosaurs that once roamed Earth worked together like wolves? The question of pack ing among these prehistoric giants has captured imaginations ever since Jurassic Park showed us clever raptors coordinating attacks. Yet the truth behind dinosaur behavior remains far more complex and contentious than Hollywood would have us believe.

The scientific community continues to wrestle with this fascinating puzzle. Some fossil discoveries suggest cooperation among certain species, while mounting evidence challenges these interpretations. Let’s dive in to explore what the latest research reveals about these ancient predators and their social lives.

The Mystery of Fossil Evidence

Much of the evidence in favor of pack hunting is circumstantial, say paleontologists. “There’s actually not very much direct evidence for pack hunting in dinosaurs,” says Paul Barrett, a paleontologist and Principal Researcher with the Natural History Museum in London. The challenge lies in reading behaviors from bones that are millions of years old.

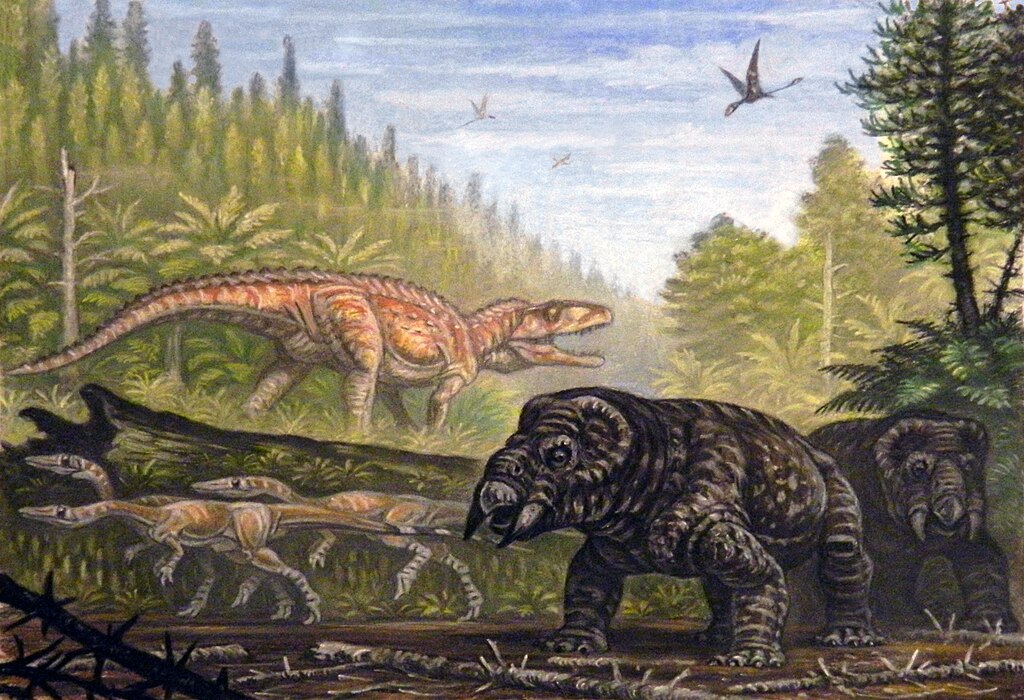

Paleontologists must piece together clues like detectives at a crime scene. What we have are a bunch of clues that taken together indicate that it may have been happening in at least some of the hunters. The first piece of the puzzle is evidence of meat-eating dinosaurs that lived in groups some of the time. Such discoveries exist: Paleontologists in 2006 found a group of Mapusaurus that appear to have lived together and, similarly, a mass grave in Utah suggests this same behavior among tyrannosaurs. Still, interpreting these finds proves tricky.

Trackway Evidence Points Both Ways

One trackway, found in China and belonging to cousins of Deinonychus, showed 6 individuals moving in the same direction. The geology suggested that the tracks were laid down very close in time to one another, potentially even simultaneously. This trackway has been cited as evidence that Deinonychus-like animals moved together in packs.

However, these tracks might tell a different story entirely. Komodo dragons leave similar footprints because when they smell or hear that a Komodo dragon has taken down an animal, all of the dragons in that area will head to the kill site. If this were fossilized, the tracks would look like the China trackway, with numerous individuals heading in the same direction. The tracks could represent scavengers converging on a meal rather than coordinated hunters.

The Famous Deinonychus Discovery

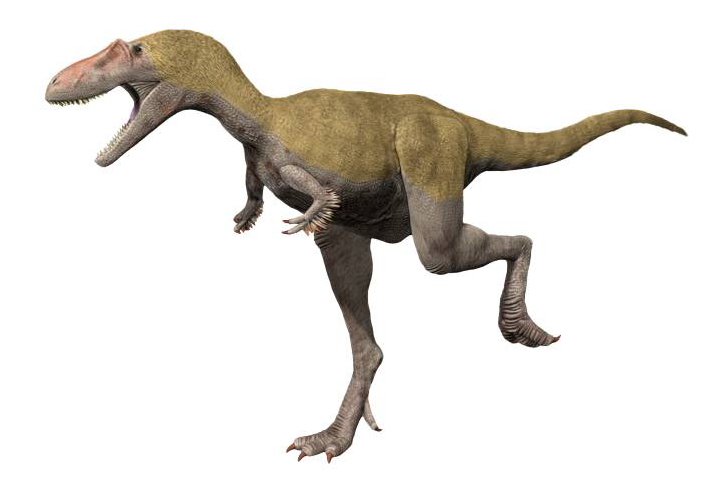

When the first fossils of a dinosaur called Deinonychus were found – a 6-foot-(1.8-meter-) tall, 11-foot (3.4-meter-) long Cretaceous period predator of western North America – the remains of many of these carnivores were clustered near the body of a large herbivore, a Tenontosaurus. Paleontologists theorized that these predators perished during the struggle with the larger dinosaur, indicating that the hunt was being conducted by a group.

This discovery sparked the pack hunting theory that dominated thinking for decades. Yet closer examination reveals complications. There is some evidence one of the raptors killed another, and that they engaged in cannibalism – suggesting they fought over the Tenontosaurus remains. His hypothesis is that the event was more akin to a Komodo dragon kill than a wolf pack hunt.

The Albertosaurus Bone Bed Mystery

In 1910, American paleontologist Barnum Brown discovered the remains of a large group of Albertosaurus at another quarry alongside the Red Deer River. Because of the large number of bones and the limited time available, Brown’s party did not collect every specimen, but made sure to collect remains from all of the individuals that they could identify in the bone bed. This indicated the presence of at least nine individuals in the quarry.

Today the Albertosaurus bonebed is famous among dinosaur researchers as the best evidence tyrannosaurs lived in social groups. The bonebed was actually discovered in 1910 by pioneering palaeontologist Barnum Brown. Currie says Brown realized that his find was strong evidence that Albertosaurus lived in packs, but he did not explore the idea any further. The site contains individuals of different ages, suggesting family groups rather than temporary aggregations.

Modern Comparisons Challenge Pack Theory

The problem with this idea is that living dinosaurs (birds) and their relatives (crocodilians) do not usually hunt in groups and rarely ever hunt prey larger than themselves. Scientists increasingly look to modern relatives for behavioral insights, and the comparisons don’t support coordinated pack hunting.

Paleontologists recently proposed a different model for behavior in raptors that is thought to be more like Komodo dragons or crocodiles, in which individuals may attack the same animal but cooperation is limited. In Komodo dragons, babies are at risk of being eaten by adults, so they take refuge in trees, where they find a wealth of food unavailable to their larger ground-dwelling parents. Animals that hunt in packs do not generally show this dietary diversity.

Chemical Analysis Reveals the Truth

Dr. Frederickson and his colleagues from the University of Oklahoma and the Sam Noble Museum analyzed the chemistry of teeth from Deinonychus antirrhopus. “We also see the same pattern in the raptors, where the smallest teeth and the large teeth do not have the same average carbon isotope values, indicating they were eating different foods. This means the young were not being fed by the adults, which is why we believe Jurassic Park was wrong about raptor behavior.”

This isotope analysis provides compelling evidence against pack hunting behavior. This is what we would expect for an animal where the parents do not provide food for their young. True pack hunters typically share resources and feed their young collectively, but the chemical signatures in dinosaur teeth tell a different story.

What the Evidence Really Shows

Some evidence that has previously been proposed in support of highly gregarious, mammal-like behavior in nonavian theropods (e.g., certain theropod-dominated fossil assemblages, preserved bite-mark injuries on some specimens, and the preponderance of theropod trackways at some sites) may alternatively be interpreted as evidence that nonavian theropod behavior was more agonistic, cannibalistic, and diapsid-like than has been widely believed.

Rather than coordinated hunting, the fossil record might actually show aggressive competition between individuals. Others have speculated that, instead of social groups, at least some of these finds represent Komodo dragon-like mobbing of carcasses, where aggressive competition leads to some of the predators being killed and even cannibalized. This interpretation fits better with what we know about modern reptilian behavior.

Conclusion

The dream of pack-hunting dinosaurs working together like prehistoric wolves appears to be just that – a dream. While some species may have occasionally gathered in groups, the evidence increasingly points toward solitary hunters or loose aggregations rather than coordinated pack behavior. The chemical analysis of teeth, comparisons with modern reptiles, and reexamination of fossil sites all challenge the Hollywood image of clever, cooperative dinosaurs.

This doesn’t make dinosaurs any less fascinating. These ancient predators were perfectly adapted to their environments as individual hunters, using their incredible senses, speed, and deadly weapons to survive. Sometimes the truth about prehistoric life proves even more amazing than fiction. What do you think about it? Tell us in the comments.