Dong Zhiming, often called the “Father of Chinese Dinosaurs,” transformed paleontology in China through his groundbreaking discoveries and tireless dedication to the field. His work not only unearthed countless dinosaur fossils across China’s vast landscapes but also established the country as a global center for paleontological research. From humble beginnings during a politically turbulent era to becoming an internationally recognized scientist, Dong’s journey mirrors China’s own scientific renaissance. His discoveries have fundamentally changed our understanding of dinosaur evolution, migration patterns, and the prehistoric world. This article explores the remarkable life and legacy of a man whose passion for ancient reptiles helped rewrite the history of life on Earth.

Early Life and Education During Turbulent Times

Born in 1937 in Shandong Province, Dong Zhiming came of age during one of the most tumultuous periods in modern Chinese history. His childhood coincided with the Japanese occupation and the subsequent Chinese Civil War, creating an environment where educational opportunities were limited and often disrupted. Despite these challenges, Dong showed an early aptitude for natural sciences and developed a curiosity about the ancient world that would define his later career. In 1956, he enrolled at the Beijing Institute of Geology (now China University of Geosciences), where he initially studied geological engineering rather than paleontology. This foundation in practical geology would later prove invaluable in his fieldwork, giving him insights into sedimentary formations and depositional environments that others might have missed. His formal education in paleontology began in earnest when he joined the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) in 1962, an institution that would become his professional home for decades.

The Cultural Revolution’s Impact on Chinese Science

Dong’s early career coincided with the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), a period of extreme political upheaval that devastated scientific research in China. During this decade, many scientists were persecuted, laboratories were closed, and academic pursuits were often deemed “bourgeois” and counter-revolutionary. Dong, like many of his colleagues, faced significant obstacles to conducting research during this period, with fieldwork curtailed and publication opportunities limited. Some paleontologists were sent to work in labor camps or factories, their expertise considered useless in the new political climate. Despite these challenges, Dong managed to continue some research activities, often working in isolated regions where political scrutiny was less intense. He used this time to meticulously study existing fossil collections and develop theories that he would later test when fieldwork became possible again. The resilience Dong showed during this difficult period would become characteristic of his approach to overcoming obstacles throughout his career, whether political or scientific in nature.

The Dashanpu Discoveries: Putting China on the Paleontological Map

In the late 1970s, as China began to open up following the Cultural Revolution, Dong led excavations at the Dashanpu Formation in Sichuan Province that would transform dinosaur paleontology in China. This site yielded a treasure trove of Jurassic dinosaurs, including the massive sauropod Mamenchisaurus, known for having the longest neck of any dinosaur relative to its body size. The Dashanpu discoveries also included Tuojiangosaurus, an important stegosaur, and Gasosaurus, a theropod that added new dimensions to understanding dinosaur diversity during the Middle to Late Jurassic period. What made these findings especially significant was their completeness – rather than fragmentary remains, Dong and his team uncovered numerous near-complete skeletons that allowed for accurate reconstructions and detailed study. The systematic way in which Dong approached these excavations, carefully documenting stratigraphic positions and preserving contextual information, set new standards for paleontological fieldwork in China. These discoveries brought international attention to Chinese paleontology and established Dong as a leading figure in the field, leading to collaborations with scientists from around the world who were eager to study these remarkable fossils.

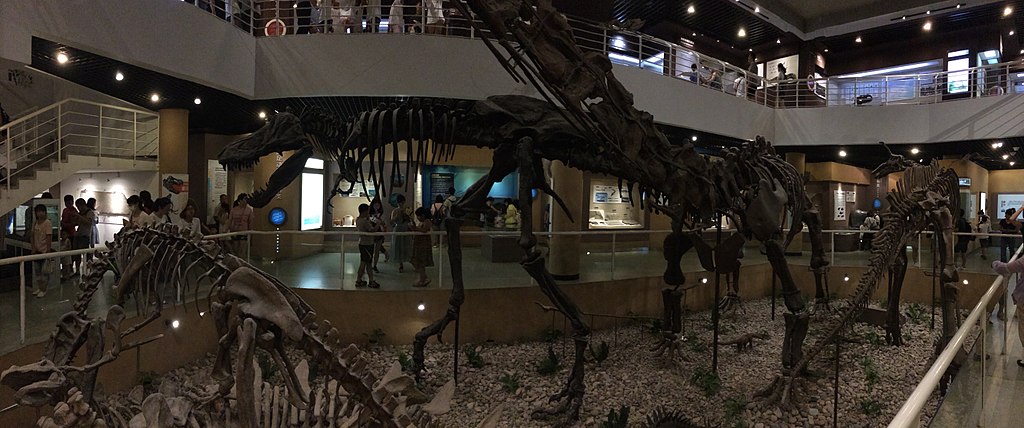

Building China’s Dinosaur Museums and Research Infrastructure

Recognizing that fossil discoveries alone were insufficient without proper facilities for study and public education, Dong became instrumental in developing China’s paleontological infrastructure. He played a pivotal role in establishing the Zigong Dinosaur Museum in Sichuan Province, which opened in 1987 as China’s first specialized dinosaur museum built on the site of a major fossil excavation. Under his guidance, this institution grew to house one of the most important dinosaur collections in Asia and became a center for both research and public education. Dong also worked tirelessly to modernize the facilities at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing, advocating for advanced laboratory equipment and expanded collection spaces. His efforts extended to training a new generation of technicians in fossil preparation techniques, ensuring that specimens were properly conserved for scientific study. Perhaps most importantly, Dong helped create networks of local fossil monitors in promising regions, training rural citizens to recognize potential fossils and report finds, thereby creating an early warning system that has led to the preservation of countless specimens that might otherwise have been lost to erosion or illegal collection.

The China-Canada Dinosaur Project: International Collaboration

One of Dong’s most significant contributions to global paleontology was his leadership in the China-Canada Dinosaur Project, a groundbreaking international collaboration that ran from 1986 to 1991. This ambitious project brought together Chinese paleontologists with their Canadian counterparts from the Royal Tyrrell Museum and other institutions to conduct joint excavations in both countries. The expeditions to the Gobi Desert and Alberta’s Dinosaur Provincial Park yielded numerous important discoveries and allowed for direct comparisons between North American and Asian dinosaur faunas. Through this collaboration, Dong facilitated the transfer of advanced techniques and technologies to Chinese paleontology while sharing China’s rich fossil resources with the international scientific community. The project resulted in the description of several new dinosaur species and generated dozens of scientific papers that transformed understanding of dinosaur evolution and paleobiogeography. Beyond the scientific outcomes, this collaboration served as a model for international scientific cooperation during a period when China was just beginning to open its scientific community to the outside world. Dong’s diplomatic skills were essential to navigating the complex political and cultural challenges involved in such a large-scale international project.

Discovering the Early Evolution of Birds in China

While Dong is primarily known for his work on dinosaurs, he also made significant contributions to understanding the dinosaur-bird transition through his research at the Yixian Formation in Liaoning Province. This exceptionally preserved fossil bed has yielded some of the most important evidence for the evolutionary link between dinosaurs and birds, including numerous feathered dinosaur specimens. Dong was among the first paleontologists to recognize the extraordinary significance of these fossils when they began to emerge in the 1990s, and he helped direct research attention to this formation. His early support for excavations in Liaoning helped establish the protocols for proper collection and study of these delicate specimens, which often preserve soft tissues and feather impressions that require special handling techniques. The discoveries from Liaoning, including Sinosauropteryx, the first non-avian dinosaur confirmed to have feathers, fundamentally changed our understanding of bird evolution and the appearance of many dinosaurs. Dong’s work in this area demonstrated his scientific versatility and willingness to follow the evidence even when it led to revolutionary new understandings that challenged established views in paleontology.

Scientific Contributions: New Species and Taxonomic Work

Throughout his career, Dong personally described and named dozens of new dinosaur species, making him one of the most prolific taxonomists in the field of dinosaur paleontology. His descriptions include iconic Chinese dinosaurs such as Shunosaurus, a well-preserved sauropod with a club-like tail; Yangchuanosaurus, an important large theropod; and numerous species of titanosaurs that have helped clarify sauropod evolution in Asia. Dong’s taxonomic work was characterized by meticulous attention to detail and conservative methodology, avoiding the tendency toward taxonomic inflation that has sometimes affected dinosaur paleontology. He developed particular expertise in sauropod dinosaurs, becoming a globally recognized authority on this group and contributing significantly to understanding their diversity in Asia. Beyond merely naming new species, Dong conducted important comparative studies that placed Chinese dinosaurs in a global context, identifying patterns of provincialism and migration that helped explain dinosaur distribution across continents. His comprehensive monographs on specific dinosaur groups have become standard references in the field, demonstrating his ability to synthesize large amounts of information into coherent evolutionary frameworks.

Mentoring China’s Next Generation of Paleontologists

Perhaps one of Dong’s most enduring legacies has been his role as a mentor and teacher to several generations of Chinese paleontologists. Throughout his career at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, he supervised dozens of graduate students who have gone on to become leading researchers in their own right. His mentoring philosophy emphasized both rigorous scientific methodology and the importance of fieldwork, ensuring that his students developed comprehensive skills as paleontologists. Dong was known for his generosity in sharing research opportunities with younger colleagues, often including students as co-authors on important papers and giving them opportunities to present at international conferences. Many of today’s prominent Chinese paleontologists, including Xu Xing, Wang Xiaolin, and Zhou Zhonghe, acknowledge Dong’s influence on their careers and research approaches. Beyond formal mentoring relationships, Dong regularly gave lectures at universities throughout China to inspire students to consider careers in paleontology, helping to address the shortage of trained professionals in the field. His accessible communication style and evident passion for dinosaurs made him particularly effective at recruiting new talent to paleontology during a period when many bright students were choosing more lucrative career paths.

Public Education and Popularizing Dinosaurs in China

Recognizing that public support was essential for the continued development of paleontology in China, Dong became an enthusiastic science communicator who worked tirelessly to make dinosaurs accessible to the general public. He authored numerous popular books on dinosaurs in Chinese, including “The World of Dinosaurs,” which introduced generations of Chinese children to paleontology and remains a bestseller decades after its initial publication. Dong regularly appeared in television documentaries and gave public lectures throughout China, becoming a familiar face associated with dinosaur discoveries. His ability to explain complex scientific concepts in clear, engaging language made him particularly effective at bridging the gap between academic research and public understanding. Dong also worked closely with museum exhibit designers to ensure that dinosaur displays were both scientifically accurate and appealing to visitors, leading to a significant improvement in the quality of paleontological exhibitions throughout China. Through these various outreach activities, he helped cultivate a widespread public fascination with dinosaurs in China that has created a supportive environment for paleontological research and conservation efforts.

Advocating for Fossil Protection Laws in China

As China’s economic development accelerated in the 1980s and 1990s, construction projects and commercial fossil hunting began to threaten many important paleontological sites. Dong became a vocal advocate for stronger legal protections for fossils and worked with government officials to develop more comprehensive legislation. He was instrumental in drafting regulations that classified important fossils as national treasures and restricted their export, helping to combat the international black market trade in Chinese specimens. Dong also helped establish protected status for key fossil localities, ensuring that construction projects would require paleontological assessment before proceeding in sensitive areas. His advocacy extended to the creation of geoparks around particularly significant sites, creating a dual benefit of protecting fossils while developing sustainable tourism opportunities for local communities. When illegal fossil poaching became a serious problem in some regions, Dong helped develop training programs for local law enforcement to recognize valuable specimens and understand applicable laws. His persistent advocacy on these issues helped create a legal framework that balances scientific interests with economic development, though challenges in enforcement remain an ongoing concern in Chinese paleontology.

Global Recognition and International Honors

As Dong’s scientific contributions gained worldwide recognition, he received numerous prestigious awards and honors throughout his career. In 1997, he was elected as a foreign associate of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, a rare distinction for a Chinese scientist at that time. The Society of Vertebrate Paleontology awarded him the Romer-Simpson Medal, its highest honor, in recognition of his sustained and outstanding contributions to the field. Several dinosaur species have been named in his honor, including Dongbeititan dongi and Tianyulong confuciusi (using his courtesy name), testaments to his stature in the paleontological community. Universities around the world, including the University of Alberta and the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, have awarded him honorary degrees and research fellowships. Despite receiving these international accolades, Dong remained notably humble and continued to focus on fieldwork and research rather than seeking public recognition. These honors not only acknowledged Dong’s personal achievements but also symbolized the growing global respect for Chinese paleontology that his work had helped foster over the decades.

China’s Rise as a Paleontological Superpower

When Dong began his career, Chinese paleontology was relatively marginal in the global scientific community, with limited resources and international recognition. Today, largely due to his pioneering efforts and strategic vision, China has emerged as what many consider the world’s leading center for dinosaur paleontology. The country now hosts more active dinosaur excavations than any other nation and publishes a substantial percentage of all new dinosaur descriptions annually. Chinese institutions have developed world-class laboratory facilities for preparing and studying fossils, including advanced imaging technologies that were unavailable during the early years of Dong’s career. International collaborations that Dong helped initiate have evolved into regular partnerships between Chinese paleontologists and colleagues around the world, facilitating the free exchange of ideas and methodologies. Perhaps most significantly, China now produces many paleontologists trained to the highest international standards, who are making their own groundbreaking discoveries and publishing in top scientific journals. This transformation from scientific backwater to global leader represents the fulfillment of Dong’s vision for Chinese paleontology and stands as perhaps his greatest achievement.

Legacy and Continuing Influence

Even in retirement, Dong Zhiming’s influence on Chinese paleontology remains profound. The methodologies he established for fieldwork, fossil preparation, and analysis continue to guide research throughout China. The institutional frameworks he helped build, from museums to university programs to field stations, provide the infrastructure for ongoing discoveries. Young paleontologists still study his publications as fundamental texts, and his systematic approach to documenting China’s dinosaur fauna serves as a model for comprehensive regional studies. Beyond these tangible legacies, Dong’s personal qualities – his scientific integrity, collaborative spirit, and dedication to both rigorous research and public education – have become core values of the Chinese paleontological community. His life story, rising from humble beginnings during a turbulent historical period to international scientific prominence, continues to inspire students considering careers in paleontology. As new technologies enable even more detailed analysis of fossils and as fieldwork expands into previously unexplored regions of China, each new discovery builds upon the foundation that Dong established through his decades of pioneering work.

Conclusion

Dong Zhiming’s extraordinary career transformed not just Chinese paleontology but our global understanding of dinosaurs and their world. From navigating the political challenges of the Cultural Revolution to building international collaborations and mentoring future leaders, his contributions extend far beyond his numerous scientific publications. Through his discoveries, China emerged as a paleontological powerhouse, rewriting chapters of prehistoric life that had been based largely on Western fossil finds. As both a meticulous scientist and a passionate communicator, Dong bridged the gap between academic research and public fascination with dinosaurs, creating a legacy that continues to unfold in museum halls and remote fossil beds across China. The dinosaur renaissance he sparked has not only illuminated Earth’s ancient past but also demonstrated how science can transcend political and cultural boundaries in the pursuit of knowledge.