Deep within the annals of paleontology, few mysteries have captured the imagination quite like the sounds that once echoed from the throats of dinosaurs. For decades, these ancient vocalizations remained lost to time, confined to creative speculation in films and popular media. Enter Dr. Julia Clarke, a groundbreaking paleontologist whose revolutionary research has fundamentally transformed our understanding of dinosaur vocalization. Through meticulous examination of fossil evidence, comparative anatomy, and evolutionary biology, Clarke has pieced together compelling insights into how dinosaurs may have communicated. Her work not only challenges long-held assumptions but opens new windows into the acoustic landscape of the Mesozoic Era, where the calls of these magnificent creatures once dominated Earth’s soundscape.

The Pioneering Paleontologist: Dr. Julia Clarke’s Background

Dr. Julia Clarke stands as one of the most influential figures in modern paleontology, particularly in the specialized field of vertebrate evolution and avian paleobiology. A distinguished professor at the University of Texas at Austin’s Jackson School of Geosciences, Clarke has dedicated her career to unraveling the complex evolutionary relationships between modern birds and their dinosaurian ancestors. Her academic journey includes degrees from Brown University and Yale University, where she honed her expertise in comparative anatomy and evolutionary biology. Beyond her academic credentials, Clarke has conducted fieldwork across multiple continents, discovering crucial fossil evidence that has redefined our understanding of dinosaur-bird evolution. Her methodical approach combines traditional paleontological techniques with cutting-edge technology to extract maximum information from the fossil record, making her uniquely qualified to tackle the challenging question of dinosaur vocalization.

The Silent Fossil Record: Challenges in Studying Ancient Sounds

Reconstructing dinosaur vocalizations presents unique challenges that have long frustrated paleontologists seeking to understand these extinct creatures. Unlike bones, which can fossilize under the right conditions, sounds leave no direct physical evidence in the geological record. This fundamental obstacle has forced scientists to rely on indirect evidence and comparative anatomy to make educated inferences about dinosaur communication. The delicate vocal structures of animals, composed primarily of soft tissues including cartilage, muscles, and membranes, rarely survive the fossilization process, creating significant gaps in our understanding. Additionally, the acoustic properties of prehistoric environments differed substantially from modern ones, affecting how sounds would have traveled and been perceived. These challenges collectively explain why dinosaur vocalizations remained largely in the realm of speculation until Clarke’s groundbreaking research began connecting critical anatomical dots through careful examination of the evolutionary relationship between dinosaurs and their living descendants: birds.

The Evolutionary Link: Birds as Living Dinosaur Descendants

The scientific consensus that birds represent living dinosaurs provides the foundational framework for Dr. Clarke’s research into dinosaur vocalizations. This evolutionary connection, firmly established through decades of fossil discoveries and comparative anatomy studies, allows researchers to use modern birds as crucial reference points for understanding their extinct relatives. Birds evolved from a group of theropod dinosaurs called maniraptoran dinosaurs, preserving many anatomical features of their ancestors while developing specialized adaptations for flight and other avian characteristics. This evolutionary continuity means that studying the vocal anatomy and production mechanisms in modern birds can provide valuable insights into how their dinosaurian ancestors might have vocalized. Clarke’s research leverages this evolutionary relationship, examining how specific vocal structures evolved along the dinosaur-bird lineage and what these changes suggest about the sounds produced by various dinosaur groups. By carefully tracing the development of vocal organs through the fossil record, Clarke has established a scientifically rigorous approach to reconstructing the acoustic capabilities of creatures that vanished millions of years ago.

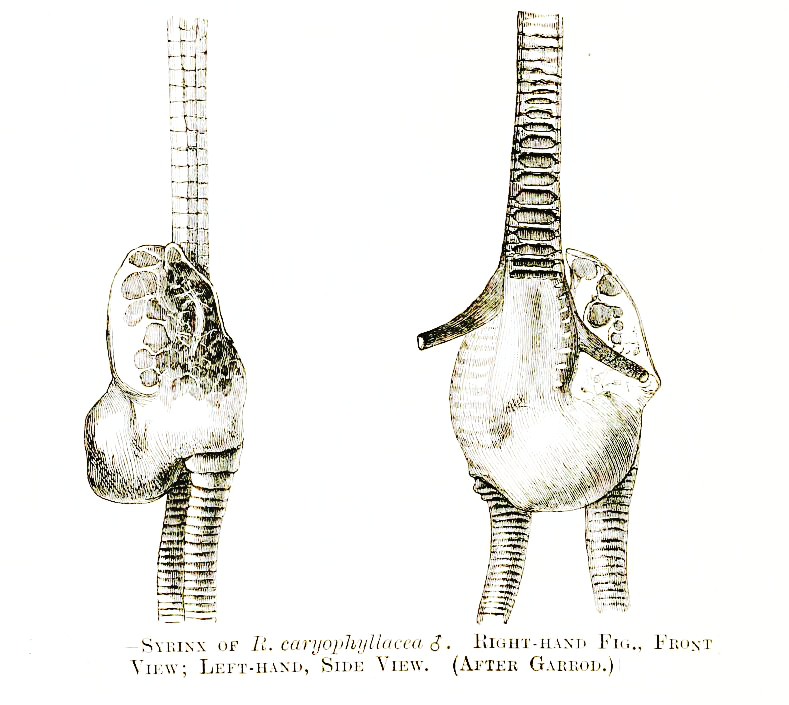

Syrinx vs. Larynx: The Key to Dinosaur Vocalization

One of Dr. Clarke’s most significant contributions to understanding dinosaur vocalizations comes from her research distinguishing between two fundamentally different sound-producing organs: the syrinx and the larynx. Modern birds produce their diverse array of calls and songs using a specialized organ called the syrinx, located at the junction where the trachea splits into the two bronchi leading to the lungs. This unique structure allows birds to produce complex, often melodious sounds with remarkable control and variation. In contrast, most non-avian vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and amphibians, vocalize using the larynx, positioned higher in the throat. Clarke’s groundbreaking research suggests that the syrinx emerged relatively late in dinosaur evolution, likely appearing around 67-69 million years ago in the immediate ancestors of modern birds. This crucial finding indicates that non-avian dinosaurs almost certainly lacked a syrinx and instead relied on a more primitive larynx-based vocalization system similar to modern crocodilians and other reptiles. The evolutionary transition from larynx to syrinx represents a fundamental shift in sound production capabilities, with profound implications for how we imagine dinosaur vocalizations sounded.

The Vegavis Discovery: Finding the Oldest Known Syrinx

Dr. Clarke’s research took a monumental leap forward with the examination of a 66-million-year-old bird fossil known as Vegavis iaai, discovered on Antarctica’s Vega Island. This Late Cretaceous bird, already significant for confirming that modern bird lineages existed alongside non-avian dinosaurs, yielded an even more remarkable secret under Clarke’s careful investigation. Using advanced imaging techniques including micro-CT scanning, Clarke and her team identified the oldest known fossilized syrinx within this specimen, providing the first direct evidence of this specialized vocal organ in the fossil record. This extraordinary discovery, published in the prestigious journal Nature in 2016, established a crucial temporal marker for the evolution of avian vocalization. The Vegavis syrinx appears fully formed and remarkably similar to those found in modern ducks and geese, suggesting this specialized vocal adaptation was already well-developed in some avian lineages by the Late Cretaceous period. The absence of syringeal structures in older fossils, including those of non-avian dinosaurs, strongly supports Clarke’s hypothesis that most dinosaurs vocalized using more primitive mechanisms and likely sounded quite different from modern birds.

Crocodilian Connections: The Sound of Ancient Reptiles

To better understand what non-avian dinosaurs might have sounded like, Dr. Clarke has drawn important parallels with another group of living archosaurs: crocodilians. Both dinosaurs and crocodilians share a common ancestor that lived approximately 250 million years ago, making modern crocodiles and alligators valuable reference points for inferring dinosaur vocal capabilities. Crocodilians produce their characteristic bellows and growls using a larynx-based vocal system, without the specialized syrinx found in birds. Clarke’s research suggests that many dinosaur groups, particularly the large non-avian species that dominated the Mesozoic ecosystems, likely employed similar laryngeal vocalization mechanisms. This evolutionary relationship indicates that dinosaur sounds may have been more reminiscent of the low-frequency rumbles, hisses, and growls produced by crocodilians rather than the melodious songs associated with modern birds. The comparative anatomy approach allows researchers to establish more scientifically grounded reconstructions of dinosaur vocalizations based on the acoustic properties of their closest living relatives, moving beyond the purely speculative portrayals common in popular media.

Debunking Hollywood: Why Dinosaurs Didn’t Roar

Dr. Clarke’s research directly challenges the popular portrayal of dinosaurs as roaring monsters frequently depicted in films like Jurassic Park. According to her findings, the iconic thunderous roars attributed to Tyrannosaurus rex and other large dinosaurs represent a fundamental misunderstanding of dinosaur vocal anatomy. True roaring requires specialized vocal anatomy found primarily in certain mammals, particularly big cats, which evolved completely independently from dinosaurs. Based on comparative studies of living dinosaur descendants (birds) and their closest living relatives (crocodilians), Clarke suggests dinosaurs were likely physically incapable of producing mammalian-style roars. Instead, non-avian dinosaurs probably made sounds more similar to the closed-mouth vocalizations observed in modern birds and crocodilians—deep, resonant booms, rumbles, and hisses produced without widely opening the mouth. This revelation transforms our auditory image of the Mesozoic landscape, replacing Hollywood’s dramatic roars with a more scientifically accurate but no less fascinating soundscape of rumbles, booms, and closed-mouth vocalizations that would still have been impressive and potentially terrifying to human ears.

Closed-Mouth Vocalization: The Likely Sound of Dinosaurs

One of the most compelling aspects of Dr. Clarke’s research focuses on a specific vocalization technique called closed-mouth vocalization or infrasound production, which likely characterized many dinosaur species. In a groundbreaking 2016 study published in the journal Evolution, Clarke and her colleagues identified this vocalization method across diverse bird lineages, from crocodile birds to doves, suggesting it represents an ancestral trait that may have been present in non-avian dinosaurs. Closed-mouth vocalization occurs when animals push air through their throats while keeping their mouths shut, creating resonant, low-frequency sounds that can travel long distances. These sounds are often felt as much as heard, capable of traveling across vast distances with minimal degradation. The anatomical requirements for this vocalization technique align well with what we know about dinosaur anatomy, providing a strong basis for inferring that many dinosaur species likely communicated using these deep, resonant calls. Clarke’s research suggests that rather than the aggressive open-mouthed roars popularized in films, dinosaurs may have been more likely to produce sounds similar to the booming calls of emus, ostriches, and cassowaries—deep, haunting vocalizations that still command attention and respect in modern environments.

Size Matters: How Body Size Influenced Dinosaur Sounds

Dr. Clarke’s research emphasizes the critical relationship between body size and vocalization capabilities in dinosaurs. The physical dimensions of an animal fundamentally constrain the frequencies it can efficiently produce, with larger animals generally capable of generating lower frequencies than smaller ones. This principle, well-established in bioacoustics, suggests that massive dinosaurs like Brachiosaurus or Apatosaurus would have produced extremely low-frequency vocalizations, potentially even infrasound below the threshold of human hearing. These massive sauropods, with their long necks and enormous resonating chambers, may have generated sounds felt through the ground as much as heard through the air, similar to how elephants use infrasound to communicate over long distances. Meanwhile, smaller theropods likely produced higher-pitched vocalizations, with the smallest dinosaurs potentially capable of chirps and calls in frequencies similar to some modern birds. This size-based acoustic diversity would have created a layered soundscape across the Mesozoic era, with different dinosaur groups occupying distinct “acoustic niches” based largely on their physical dimensions. Clarke’s work in correlating body size with vocal characteristics provides a crucial framework for reconstructing this ancient acoustic environment with greater scientific accuracy.

Beyond Vocalization: Dinosaur Communication Systems

Dr. Clarke’s research on dinosaur vocalization fits within a broader understanding that these ancient creatures likely employed multi-modal communication systems extending far beyond vocal sounds. Visual displays played a crucial role in dinosaur communication, as evidenced by the elaborate crests, frills, and display structures preserved in the fossil record. Many dinosaur species possessed vividly colored feathers, scales, or skin that likely served communication functions similar to the display features seen in modern birds. Physical behaviors, including ritualized movements, head-bobbing, tail-wagging, and stomping, would have complemented vocal signals to create complex communication systems. Clarke’s holistic approach acknowledges that vocalizations represented just one component of dinosaur communication, working in concert with visual and behavioral signals to facilitate social interactions, territorial displays, and mating rituals. This comprehensive view of dinosaur communication systems explains why focusing solely on vocal reconstructions provides an incomplete picture of how these animals interacted with each other. By considering the full range of communication modalities available to dinosaurs, Clarke’s research offers a more nuanced understanding of dinosaur behavior and social dynamics.

Technological Innovations: How Modern Tools Aid Ancient Sound Recreation

The remarkable advances in Dr. Clarke’s research have been made possible by cutting-edge technologies that allow unprecedented analysis of fossil evidence and comparative anatomy. High-resolution computed tomography (CT) scanning has revolutionized the field by enabling researchers to examine the internal structures of fossils without damaging the specimens, revealing delicate features that would otherwise remain hidden. These scans generate detailed three-dimensional models that can be manipulated digitally, allowing scientists to measure and analyze anatomical features with exceptional precision. Digital sound synthesis techniques, developed in collaboration with acoustics experts, enable researchers to model how sound would propagate through reconstructed vocal tracts based on the physical properties of preserved anatomical structures. Comparative anatomy software allows rapid comparison between fossil specimens and extensive databases of modern animal anatomies, identifying evolutionary patterns and relationships that inform vocalization reconstructions. Additionally, paleoacoustic modeling uses principles of physics and biomechanics to simulate how different anatomical configurations would have influenced sound production capabilities. These technological innovations collectively provide Clarke and her colleagues with powerful tools to transform fragmentary fossil evidence into compelling reconstructions of dinosaur vocalizations grounded in scientific principles rather than speculation.

Educational Impact: Changing How We Teach About Dinosaurs

Dr. Clarke’s pioneering research has had profound implications for dinosaur education, fundamentally changing how these creatures are presented in museums, textbooks, and educational programs worldwide. Major natural history museums have updated their dinosaur exhibits to incorporate new findings about dinosaur vocalization, often including interactive audio installations that allow visitors to experience scientifically informed reconstructions of dinosaur sounds. Educational curricula have evolved to emphasize the evolutionary connections between dinosaurs and birds, using vocalization as a compelling example of how paleontologists use evidence-based approaches to understand extinct animals. Clarke herself has been actively involved in public outreach, collaborating with science centers to develop exhibits that showcase the methodology behind vocal reconstructions, demonstrating how scientists combine fossil evidence with comparative anatomy to draw conclusions about dinosaur sounds. Documentary filmmakers have increasingly consulted Clarke and her colleagues to create more accurate portrayals of dinosaur vocalizations, gradually shifting public perception away from the familiar but unrealistic roars popularized by entertainment media. This educational impact represents one of the most significant aspects of Clarke’s legacy, as her research helps transform dinosaur education from simplistic characterizations to more nuanced, scientifically grounded understanding.

Future Frontiers: Ongoing Research and Unanswered Questions

Despite the remarkable progress made through Dr. Clarke’s research, significant questions about dinosaur vocalization remain unanswered, driving ongoing research in this fascinating field. Current investigations focus on identifying transitional vocal structures in the fossil record, particularly examining specimens that might preserve evidence of early syringeal development or specialized laryngeal adaptations. Researchers are developing increasingly sophisticated computer models to simulate sound production based on reconstructed vocal tract anatomies, incorporating variables such as air sac systems and resonance chambers. Comparative studies across diverse modern bird and reptile species continue to refine our understanding of the relationship between vocal anatomy and sound characteristics, providing stronger reference points for dinosaur vocalization reconstructions. Field researchers are also investigating the acoustic properties of environments similar to those of the Mesozoic era, considering how dinosaur vocalizations would have propagated through ancient forests, plains, and coastal regions. Additionally, new fossil discoveries continue to fill crucial gaps in our understanding of dinosaur anatomy, occasionally yielding rare preserved throat regions that may contain evidence relevant to vocalization capabilities. As technology advances and new specimens emerge, Dr. Clarke’s pioneering approach continues to guide researchers exploring the acoustic world of dinosaurs, promising even more refined understanding in the coming decades.

Conclusion: Redefining Our Connection to the Prehistoric World

Dr. Julia Clarke’s groundbreaking research into dinosaur vocalization represents far more than an academic curiosity—it fundamentally transforms our connection to Earth’s prehistoric past. By replacing speculative dinosaur roars with scientifically grounded reconstructions based on anatomical evidence, evolutionary relationships, and bioacoustic principles, Clarke has helped bring us closer to experiencing the Mesozoic world as it truly existed. This shift from imagination to evidence-based reconstruction exemplifies the evolving nature of paleontology, where technological innovations and interdisciplinary approaches continuously refine our understanding of extinct life. Through her meticulous research, public outreach, and educational contributions, Clarke has demonstrated how scientific investigation can enhance rather than diminish our sense of wonder about dinosaurs. The deep rumbles, infrasonic vibrations, and closed-mouth vocalizations that likely characterized dinosaur communication offer a fascinating acoustic landscape no less impressive than Hollywood’s dramatic roars—and with the added value of scientific credibility. As we continue to refine our understanding of how dinosaurs sounded, guided by the foundational work of researchers like Dr. Clarke, we forge a deeper