Florence Bascom broke barriers in the male-dominated field of geology during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, becoming a pioneering force for women in science. As one of the first female geologists in the United States, she not only made significant contributions to our understanding of Earth’s geological formations but also created pathways for future generations of women scientists. Her meticulous research on rock formations, particularly in the Appalachian Mountains, established her as a respected authority in petrography and geomorphology. Through her teaching at Bryn Mawr College and her work with the U.S. Geological Survey, Bascom demonstrated that scientific excellence knows no gender, inspiring countless women to pursue careers in geology, paleontology, and other scientific disciplines previously considered the exclusive domain of men.

Early Life and Educational Foundation

Florence Bascom was born on July 14, 1862, in Williamstown, Massachusetts, to parents who valued education and progressive thinking. Her father, John Bascom, served as the president of the University of Wisconsin and was an advocate for women’s education—a relatively radical position for the time. This supportive family environment nurtured Florence’s early interest in the natural sciences and provided her with the encouragement necessary to pursue higher education. She received her bachelor’s degree from the University of Wisconsin in 1882, followed by a second bachelor’s degree in 1884, and eventually a master’s degree in 1887 from the same institution. Bascom’s educational journey was remarkable for a woman of her era, as universities were just beginning to open their doors to female students, particularly in scientific fields. These formative years established the intellectual foundation upon which she would build her groundbreaking career in geology.

Breaking Barriers: Doctorate in Geology

Florence Bascom’s pursuit of a doctorate represented a watershed moment for women in scientific academia. In 1893, she became the second woman in the United States to earn a Ph.D. in geology, receiving her degree from Johns Hopkins University—an institution that had initially required her to sit behind a screen during lectures to prevent her from “distracting” male students. Despite these demeaning conditions, Bascom persevered with extraordinary determination, completing a dissertation on the crystalline rocks of the Piedmont region. Her doctoral research involved innovative petrographic analysis techniques and demonstrated exceptional scientific rigor that could not be ignored even by skeptical male colleagues. This achievement was not merely personal; it represented a critical crack in the glass ceiling of geological sciences, proving that women could conduct original research of the highest caliber. Bascom’s doctorate became a powerful symbol for aspiring female scientists who could now point to a precedent for their academic ambitions.

Pioneering Work in Petrography

Bascom’s most significant scientific contributions came in the field of petrography—the detailed study and classification of rocks using microscopic analysis. She developed innovative techniques for identifying and studying metamorphic rocks, particularly those in the Appalachian Mountain region, which had previously been misclassified by earlier geologists. Using the then-new technology of polarized light microscopy, Bascom conducted detailed analyses of rock thin sections, revealing their mineral composition, texture, and formation history with unprecedented accuracy. Her 1896 paper on the ancient volcanic flows of South Mountain was groundbreaking, as it conclusively demonstrated that these formations were metamorphosed lava flows rather than sedimentary deposits as previously believed. This research fundamentally changed geological understanding of the region’s formation history and established Bascom as an authority in microscopic petrography. Her meticulous methodology and attention to detail set new standards for geological research that influenced generations of scientists who followed in her footsteps.

First Female Geologist of the U.S. Geological Survey

In 1896, Florence Bascom achieved another historic milestone when she became the first woman hired by the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the nation’s premier earth science agency. Her appointment came at a time when professional scientific positions were almost exclusively reserved for men, making this achievement particularly remarkable. Initially appointed as an assistant geologist, Bascom’s exceptional work eventually earned her a full geologist position, though it took significantly longer than it would have for her male counterparts with similar qualifications. At the USGS, she conducted extensive fieldwork in the Mid-Atlantic region, mapping geological formations and producing authoritative reports that became reference materials for both academic and practical applications. Her detailed mapping of the crystalline rocks in Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey established the geological framework for understanding these complex regions. Bascom’s tenure at the USGS not only produced valuable scientific knowledge but also demonstrated that women could successfully conduct demanding field research despite prevailing social prejudices about female physical and intellectual capabilities.

Establishing Geology at Bryn Mawr College

In 1895, Florence Bascom joined the faculty of Bryn Mawr College, where she founded one of the most respected geology departments in the country. Starting with minimal resources, she built the department from scratch, designing curricula, acquiring equipment, and establishing a geological laboratory that became renowned for its excellence. Under her leadership, the Bryn Mawr geology program developed a reputation for exceptional rigor, with students expected to meet the same high standards that Bascom had faced in her education. Her teaching philosophy emphasized the importance of fieldwork alongside theoretical knowledge, taking students on regular expeditions to conduct hands-on research in various geological settings. Many of her students reported that these field experiences were transformative, providing them with practical skills that classroom instruction alone could not impart. Over her 33-year tenure at Bryn Mawr, Bascom trained multiple generations of female geologists who went on to make their significant contributions to the field, creating a powerful legacy of women in geological sciences.

Mentorship and Legacy Through Students

Florence Bascom’s most enduring contribution to science may have been her role as a mentor to numerous women who followed her into geology. She trained more than 300 students during her career at Bryn Mawr, many of whom became significant figures in their own right in geology and paleontology. Among her most notable students were Eleanora Bliss Knopf, who became an expert on structural geology, Anna Jonas Stose, who made important contributions to Appalachian geology, and Julia Gardner, who became a renowned paleontologist with the U.S. Geological Survey. Bascom was known for her exacting standards but also for her unwavering support of talented students regardless of their gender. Many of her former students later reported that Bascom’s belief in their abilities gave them the confidence to pursue careers in a field where women were still largely unwelcome. This “academic lineage” that Bascom established created a network of female geologists who supported each other professionally, gradually increasing women’s representation in geological sciences. Through this mentorship, Bascom’s influence extended far beyond her scientific achievements into the work of subsequent generations.

Contributions to Geomorphology

Beyond her work in petrography, Bascom made significant contributions to the field of geomorphology—the study of Earth’s physical features and the processes that shape them. Her research on the evolution of landscape forms in the Piedmont and Appalachian regions provided important insights into how geological processes shape terrain over time. Bascom conducted detailed studies of erosion cycles and their effects on landforms, contributing to the development of the Davisian system of geomorphology, which described how landscapes evolve through stages of youth, maturity, and old age. She mapped numerous examples of peneplains—nearly flat surfaces produced by long periods of erosion, which helped confirm key aspects of this theoretical framework. Her 1921 paper on the erosional history of the Appalachian region demonstrated how differential erosion of varying rock types created the distinctive landscape features visible today. These contributions to geomorphology were particularly valuable because they connected microscopic rock analysis with large-scale landscape features, bridging different scales of geological understanding. Bascom’s geomorphological work continues to influence how geologists interpret landscape evolution and regional geological history.

Professional Recognition Against All Odds

Despite the pervasive gender discrimination of her era, Florence Bascom eventually received significant professional recognition for her scientific achievements. In 1901, she became the first woman elected to the Geological Society of America, a major professional milestone that acknowledged her contributions to the field. By 1924, she had been promoted to vice president of this prestigious organization, demonstrating her high standing among peers despite ongoing prejudices. Scientific journals that had initially been reluctant to publish work by female scientists came to recognize the value of her meticulous research, publishing her findings in major geological publications. The American Men of Science (later renamed American Men and Women of Science) listed Bascom among the country’s top 100 geologists, an exceptional honor that reflected her scientific impact rather than her gender. These recognitions came not through any lowering of standards but because Bascom’s work was simply too significant to ignore, even by those who questioned women’s place in science. Her ability to achieve this recognition while facing additional barriers demonstrates both her exceptional scientific abilities and her remarkable determination to succeed in her chosen field.

Fieldwork Challenges for a Female Geologist

Florence Bascom conducted extensive geological fieldwork at a time when such activities were considered highly inappropriate for women. The physical demands of geological fieldwork—hiking rough terrain, climbing rock formations, camping in remote areas—directly contradicted Victorian notions of feminine delicacy and propriety. Bascom overcame these social restrictions by adopting practical field attire that scandalized some contemporaries but allowed her to work effectively, often wearing split skirts or bloomers that permitted greater freedom of movement while maintaining some concession to period expectations of female dress. She frequently conducted fieldwork alone or with female students in areas where few women ventured without male escorts, challenging social conventions while collecting vital geological data. During her field expeditions, Bascom sometimes faced hostile reactions from residents unaccustomed to seeing women engaged in scientific research, requiring her to develop diplomatic skills alongside her scientific ones. Despite these additional challenges that her male colleagues did not face, Bascom’s field observations and geological maps were renowned for their exceptional accuracy and detail, setting standards that many male geologists struggled to match.

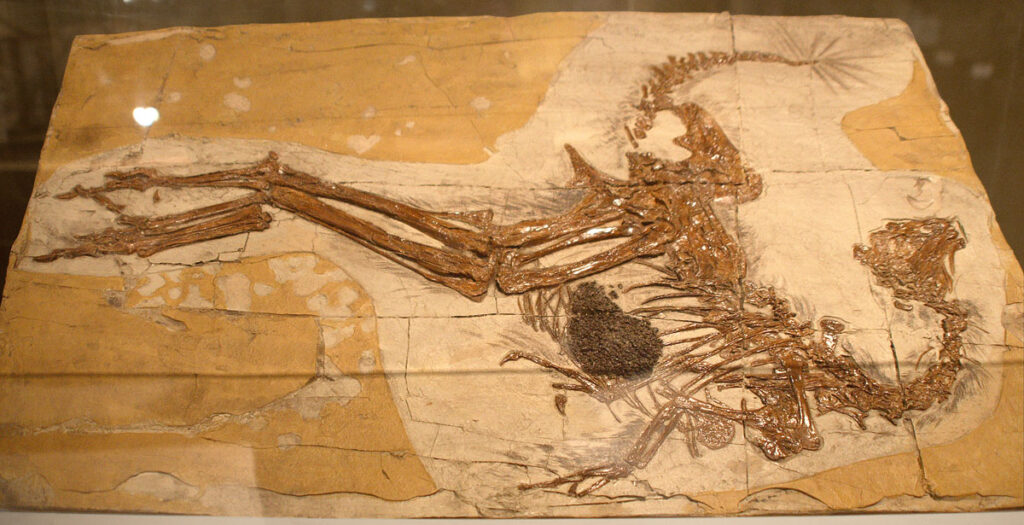

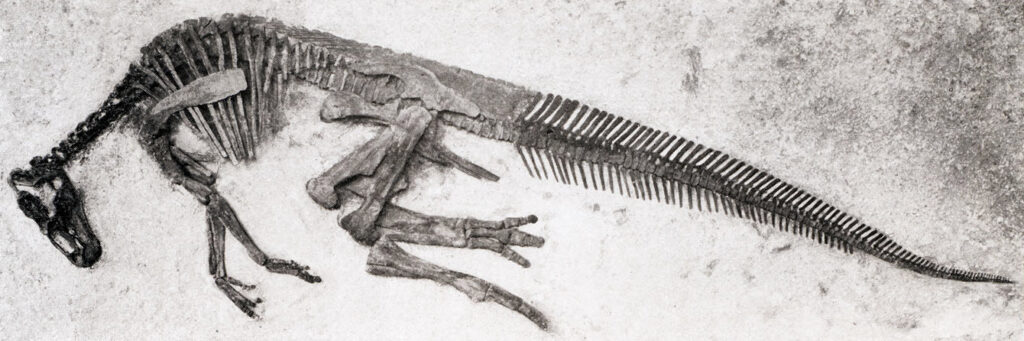

Connection to Paleontology

While primarily known as a petrologist and geomorphologist, Florence Bascom made important contributions that directly benefited the field of paleontology. Her meticulous work establishing the correct chronology and composition of rock formations provided essential context for understanding the fossil record contained within these layers. Paleontologists relied on Bascom’s detailed geological maps to locate promising fossil sites and to accurately date and contextualize their findings within Earth’s broader history. Her work identifying the true nature of metamorphosed formations helped paleontologists understand why certain rock units lacked fossils despite their sedimentary origins, resolving apparent gaps in the fossil record. Through her teaching at Bryn Mawr, Bascom trained students who later specialized in paleontology, including Julia Gardner, who became a leading expert on Tertiary fossils and stratigraphy. Bascom’s methodological emphasis on integrating multiple lines of evidence—microscopic, chemical, and field observations—influenced how paleontologists approached their research, encouraging more comprehensive analysis of fossil evidence. By establishing more accurate geological frameworks, Bascom’s work enabled paleontologists to better understand the environmental and temporal contexts in which prehistoric life existed.

Publications and Scientific Communication

Florence Bascom was a prolific author of scientific publications, producing numerous papers, geological maps, and reports throughout her career. Her writing was known for its exceptional clarity and precision, making complex geological concepts accessible without sacrificing scientific rigor. Between 1896 and 1936, she published dozens of significant papers on topics ranging from the crystalline rocks of the Piedmont to erosion cycles in the Appalachians, establishing herself as a leading authority in these areas. Bascom’s geological maps, particularly those produced during her work with the U.S. Geological Survey, set new standards for detail and accuracy, becoming essential references for both academics and applied geologists in mining and engineering. She also wrote educational materials designed to improve geological education, including laboratory guides that incorporated her innovative approaches to teaching the subject. Bascom served on editorial boards for scientific journals, helping shape geological discourse beyond her publications. Her commitment to scientific communication extended to public education as well; she gave lectures to non-specialist audiences about geological topics and advocated for better earth science education in schools, recognizing the importance of geological literacy for an increasingly industrialized society dependent on mineral resources.

Personal Life and Scientific Dedication

Florence Bascom never married, devoting herself entirely to her scientific work and the advancement of women in geology. This choice was not uncommon for pioneering professional women of her era, as the social expectations surrounding marriage often conflicted directly with serious scientific careers for women. Her papers reveal a woman of remarkable focus and discipline who maintained an extensive professional correspondence with geologists worldwide while managing her teaching responsibilities and research projects. Despite the intense demands of her professional life, Bascom maintained close friendships, particularly with female colleagues who shared similar experiences navigating male-dominated scientific institutions. She lived modestly on her academic salary, investing available resources in geological specimens and equipment for teaching rather than personal comfort. Colleagues described Bascom as reserved but warm with those she trusted, possessing a dry wit that occasionally surfaced in her lectures and personal correspondence. During rare leisure time, she enjoyed botanical studies and photography, often combining these interests with her geological fieldwork by documenting plant communities associated with particular soil types derived from different bedrock. Her sacrifices enabled her singular focus on geology, which ultimately maximized her scientific impact during a time when women faced enormous barriers to scientific achievement.

Final Years and Lasting Influence

Florence Bascom retired from Bryn Mawr College in 1928 at the age of 66, though she continued her research and association with the U.S. Geological Survey for several more years. In retirement, she remained active in geological societies and maintained correspondence with former students, many of whom had become accomplished scientists in their own right. Bascom’s health declined in her later years, and she passed away on June 18, 1945, at the age of 82. Following her death, the Geological Society of America established the Florence Bascom Geoscience Center in her honor, recognizing her foundational contributions to American geology. Modern geological institutions have created numerous fellowships and awards bearing her name, ensuring that contemporary students learn about her pioneering role. Perhaps most significantly, by the end of the 20th century, women comprised nearly half of all geology graduate students in the United States—a transformation that can be traced directly to the barriers Bascom broke and the pathways she established. Her life exemplifies how scientific excellence, when pursued with unwavering determination, can overcome prejudice and create lasting change. As both a scientist and a trailblazer, Florence Bascom’s influence continues to shape geological sciences more than a century after her groundbreaking work began.

Florence Bascom Pioneered Change in Geology and Opened Doors for Women Scientists

Florence Bascom’s remarkable life stands as a testament to the power of intellectual passion and perseverance in the face of systemic barriers. From sitting behind a screen during her doctoral studies to becoming one of the most respected geologists of her generation, she transformed the landscape of geological sciences not only through her scientific contributions but by demonstrating that gender had no bearing on scientific capability. Her meticulous work in petrography, geomorphology, and geological mapping continues to influence our understanding of Earth’s processes, while her role as an educator created a legacy of female geologists who further expanded women’s presence in the field. As we recognize the achievements of this pioneering scientist, we honor not just what she discovered about the Earth’s history, but how she changed its future by opening doors previously closed to half of humanity. Florence Bascom didn’t just study how rocks transform under pressure—she transformed under social pressure into a foundation upon which generations of women scientists could build their careers.