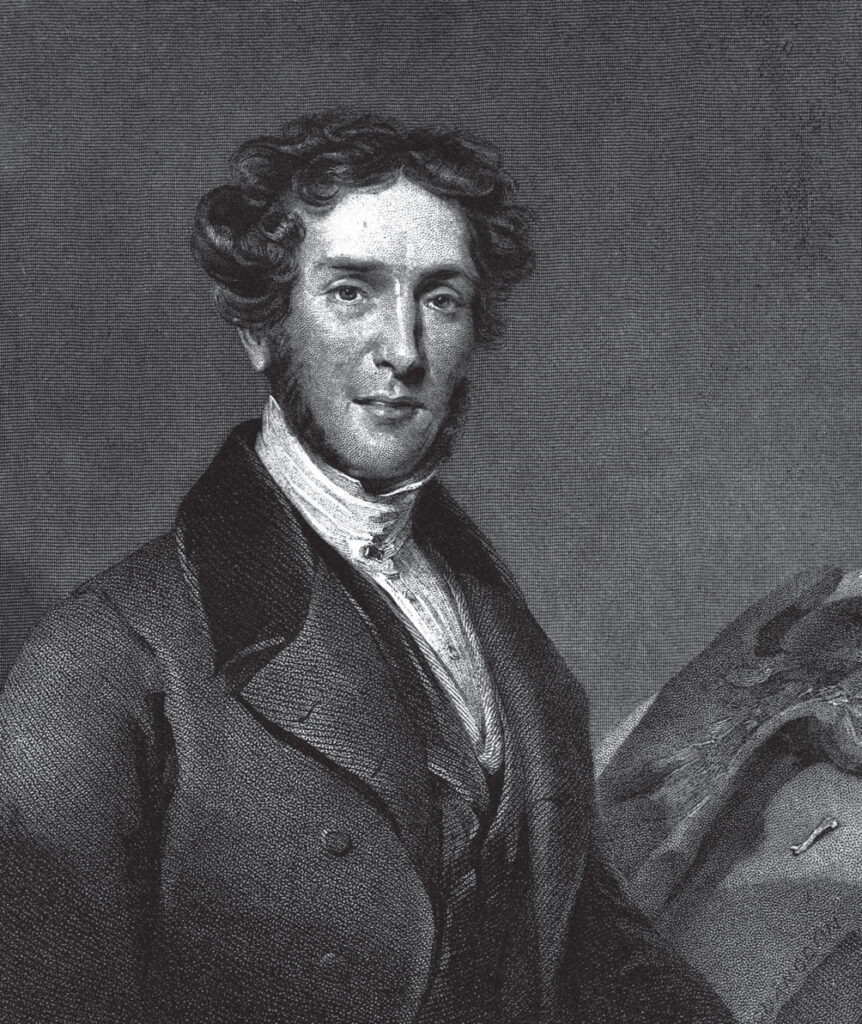

In the early 19th century, when geology and paleontology were still emerging disciplines, an unlikely figure made one of the most significant dinosaur discoveries in history. Gideon Mantell, a country doctor by profession but a passionate fossil collector by avocation, forever changed our understanding of prehistoric life when he identified and named Iguanodon, the second dinosaur ever scientifically described. His remarkable journey from medical practitioner to pioneering paleontologist exemplifies how dedication, curiosity, and meticulous observation can lead to groundbreaking scientific discoveries, even without formal training in the field.

Early Life and Medical Career

Gideon Algernon Mantell was born on February 3, 1790, in Lewes, Sussex, England, to a family of modest means. His father, Thomas Mantell, worked as a shoemaker, and despite their limited financial resources, young Gideon received a decent education at a local school. By age 15, he had become an apprentice to a local surgeon, James Moore, marking the beginning of his medical career. After completing his apprenticeship, Mantell moved to London to further his medical studies at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, eventually qualifying as a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1811. He returned to Sussex to establish his medical practice, becoming a respected physician known for his dedication to patients, particularly the poor workers of the region, whom he often treated without charge.

The Passion for Fossils

While building his medical practice, Mantell developed a growing fascination with geology and fossil collecting. The Sussex region, with its abundant chalk formations and quarries, provided a rich hunting ground for fossil enthusiasts. During his medical visits across the countryside, Mantell would often stop to examine rock exposures or chat with quarry workers about any unusual finds. He began assembling an impressive collection of fossils, minerals, and archaeological artifacts, meticulously cataloging each specimen. His home gradually transformed into a private museum that attracted visitors from across England. Unlike many gentlemen collectors of the era who viewed fossils merely as curious artifacts, Mantell approached his collection with scientific rigor, studying each specimen carefully and researching their significance, laying the groundwork for his later paleontological discoveries.

A Fateful Discovery

The pivotal moment in Mantell’s scientific career came in 1822, though the exact circumstances have become somewhat mythologized over time. According to the most commonly told version, while Mantell was visiting a patient, his wife Mary Ann explored a local quarry in Tilgate Forest and discovered several unusual teeth among a pile of road stones. Upon examining these specimens, Mantell was immediately struck by their strange appearance, noting they were unlike any fossil teeth he had previously encountered. More scholarly accounts suggest Mantell himself found the teeth during his systematic explorations of the Tilgate quarries. Regardless of the exact details, these peculiar teeth would lead Mantell to years of painstaking research and eventually to one of the most significant paleontological discoveries of the 19th century. The teeth, along with scattered bones found in the same formation, would prove to be remains of an entirely unknown prehistoric reptile.

The Challenge of Identification

Identifying the mysterious teeth proved to be an immense challenge for Mantell. The scientific establishment of the time was dominated by the views of Georges Cuvier, the leading French anatomist who believed that extinct species were simply earlier versions of modern animals. When Mantell sent casts of his specimens to Cuvier, the French scientist initially dismissed them as belonging to a rhinoceros. Undeterred, Mantell continued his investigation, comparing the teeth to those of various animals. The breakthrough came during a visit to the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, where Mantell’s friend Samuel Stutchbury pointed out the striking similarity between the fossil teeth and those of modern iguanas, only much larger. This comparison finally convinced Mantell that he had discovered the remains of a gigantic prehistoric herbivorous reptile, challenging the prevailing scientific understanding of extinct animals.

Naming Iguanodon

In 1825, after years of careful research and overcoming significant skepticism from the scientific establishment, Mantell published his findings in a paper titled “Notice on the Iguanodon, a newly discovered fossil reptile, from the sandstone of Tilgate Forest, in Sussex.” The name he chose, Iguanodon, meaning “iguana tooth,” reflected the resemblance of the fossil teeth to those of modern iguanas, though vastly larger in scale. This publication marked only the second dinosaur genus ever scientifically named, following William Buckland’s Megalosaurus the previous year. Though Mantell initially envisioned Iguanodon as a massive, iguana-like creature, his conception of the animal would evolve significantly over the coming decades as more fossil evidence came to light. His naming of Iguanodon represented a watershed moment in paleontology, helping to establish the scientific understanding that Earth had once been inhabited by creatures vastly different from modern animals.

Scientific Struggles and Opposition

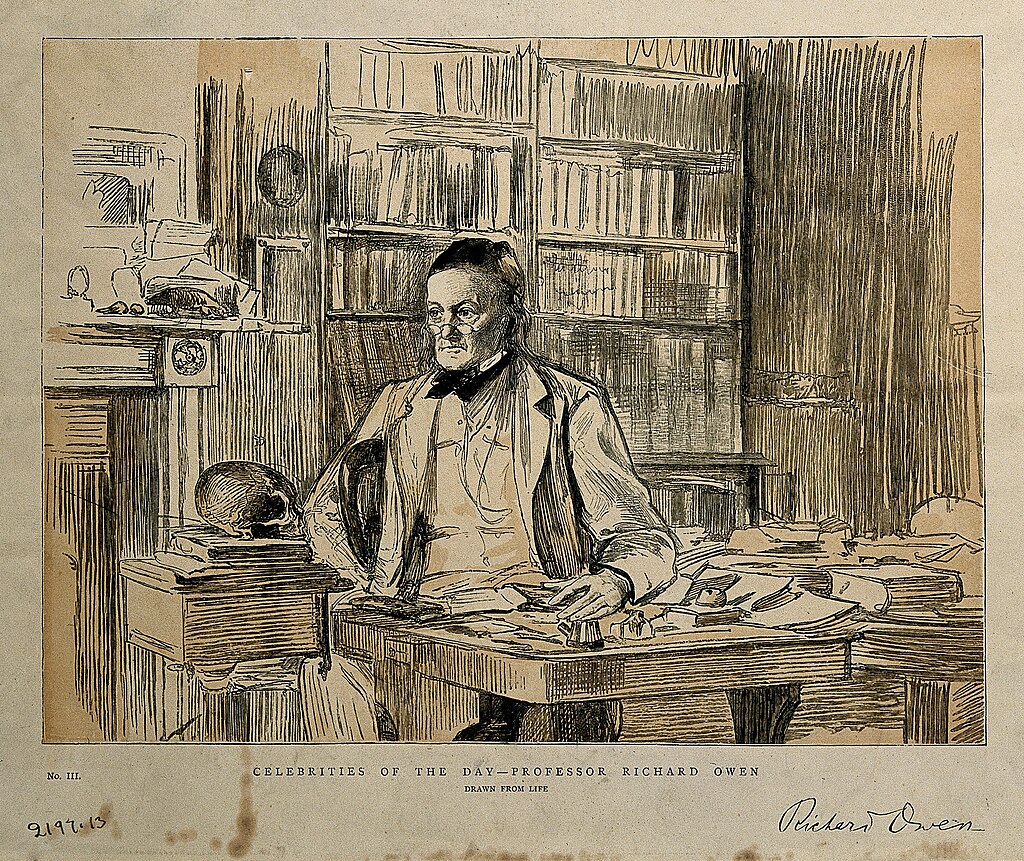

Despite the significance of his discovery, Mantell faced considerable skepticism and even hostility from certain members of the scientific establishment, particularly Richard Owen, who would later coin the term “Dinosauria.” As a provincial doctor without formal scientific training or aristocratic connections, Mantell was often treated as an outsider by the London-centered scientific elite. The Royal Society, England’s premier scientific organization, was initially reluctant to acknowledge the importance of his findings. Owen, who harbored professional jealousy toward Mantell, frequently attempted to claim credit for his discoveries or undermine their significance. These professional struggles were compounded by Owen’s greater political savvy and connections, which allowed him to position himself as the preeminent authority on prehistoric life, often at Mantell’s expense. Despite these obstacles, Mantell persisted in his research, motivated by a genuine passion for scientific discovery rather than professional ambition.

The First Dinosaur Reconstruction

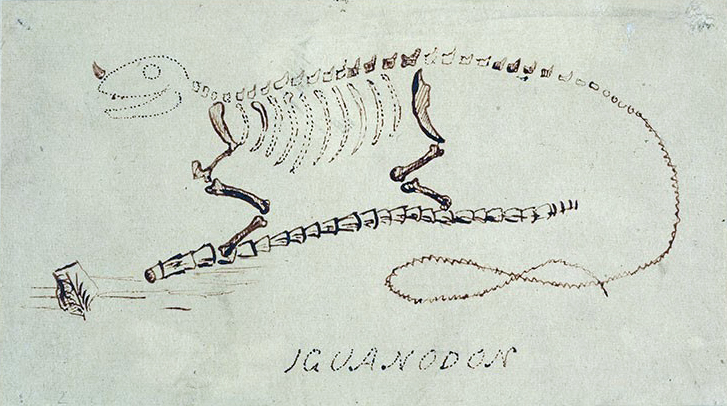

Based on the fragmentary remains available to him, Mantell attempted one of history’s first dinosaur reconstructions, though his initial conception of Iguanodon proved to be significantly flawed. Working with the limited fossil evidence and comparative anatomy knowledge of his time, Mantell originally imagined Iguanodon as a massive, quadrupedal, iguana-like creature with a horn on its nose. This “horn” was actually a thumb spike, as later discoveries would reveal, but the misinterpretation was entirely reasonable given the fragmentary nature of the fossils and the lack of any comparable living animals. In 1834, Mantell commissioned watercolor artist John Martin to create an illustration of Iguanodon as he envisioned it, resulting in one of the first artistic reconstructions of a dinosaur ever attempted. Though inaccurate by modern standards, this pioneering attempt to visualize an extinct animal based on fossil evidence represented an important step in paleontological practice.

The Maidstone Specimen

A major breakthrough in understanding Iguanodon came in 1834 when quarry workers in Maidstone, Kent, unearthed a significantly more complete Iguanodon specimen embedded in a large slab of limestone. This remarkable find, which came to be known as the “Maidstone Iguanodon,” included portions of the backbone, ribs, and limbs, providing Mantell with much more complete anatomical information about his dinosaur. Though the specimen was still far from complete by modern standards, it was substantial enough to allow for more accurate reconstructions of the animal’s size and proportions. Recognizing the specimen’s scientific importance, Mantell arranged for its purchase despite his increasing financial difficulties. The Maidstone Iguanodon became the centerpiece of Mantell’s fossil collection and provided crucial evidence that helped to verify many of his earlier suppositions about the creature he had identified from mere teeth a decade earlier.

Personal Tragedies and Perseverance

While Mantell’s scientific work was groundbreaking, his personal life was marked by significant hardships and tragedy. His obsession with fossil collecting placed considerable strain on his marriage to Mary Ann, eventually leading to their separation in 1839 after nearly thirty years together. Financial difficulties mounted as Mantell’s growing fossil collection consumed an increasing portion of his modest income, forcing him to sell his prized collection to the British Museum for a fraction of its value. In 1841, Mantell suffered a serious carriage accident that left him with a debilitating spinal deformity, causing him chronic pain for the remainder of his life. Despite these personal and physical challenges, Mantell’s passion for paleontology never diminished. He continued his scientific work, publishing papers and giving lectures while managing his constant pain, demonstrating remarkable resilience in the face of adversity.

Scientific Legacy Beyond Iguanodon

While Iguanodon remains Mantell’s most famous discovery, his contributions to paleontology extended far beyond this single genus. Throughout his career, he identified and named several other important prehistoric creatures, including Hylaeosaurus, which would later be recognized as one of the first ankylosaurs and the third dinosaur included in Richard Owen’s original Dinosauria classification. Mantell made significant contributions to understanding the Wealden geological formation of southern England, documenting its rich diversity of fossil life. He authored numerous scientific papers and several influential books, including “The Fossils of the South Downs” (1822) and “The Wonders of Geology” (1838), which helped popularize paleontology among the general public. By the end of his career, Mantell had identified more dinosaur genera than any other scientist of his era, establishing him as one of the founding figures of dinosaur paleontology despite his status as an “amateur” scientist.

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs

The fame of Mantell’s discoveries extended beyond scientific circles with the creation of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, a series of life-sized sculptures created for the Crystal Palace Park in London in the early 1850s. Designed by artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins under the scientific direction of Richard Owen, these sculptures included a prominent Iguanodon model. Ironically, the Iguanodon sculpture reflected Owen’s interpretation rather than Mantell’s, depicting the animal as a heavy, quadrupedal beast resembling a scaly rhinoceros. Although this reconstruction would later prove inaccurate, the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs marked the first time prehistoric animals had been depicted in full-scale public sculptures, capturing the Victorian public’s imagination and highlighting the cultural impact of Mantell’s discoveries. The sculptures still stand today as important historical artifacts, offering a window into early attempts to visualize extinct animals based on limited fossil evidence.

Final Years and Death

The final years of Mantell’s life were marked by increasing physical suffering and personal isolation, though his scientific work continued unabated. His spinal injury caused him excruciating pain, which he managed with increasingly large doses of opium. Despite his deteriorating health, Mantell maintained an active correspondence with scientists worldwide and continued to publish papers on his paleontological findings. On November 10, 1852, at the age of 62, Mantell died under circumstances that have been debated by historians, with some suggesting his death may have been a deliberate opium overdose to escape his constant pain. In a peculiar postscript to his life, a portion of Mantell’s spine was removed during autopsy and preserved at the Royal College of Surgeons, where it was later examined and found to show evidence of a serious disease, possibly tuberculosis of the spine, explaining the intense pain he had endured for his final decade.

Modern Understanding of Iguanodon

Subsequent discoveries have dramatically transformed our understanding of Iguanodon from Mantell’s initial conception. The most significant breakthrough came in 1878, nearly three decades after Mantell’s death, when an extraordinary discovery of more than 30 complete Iguanodon skeletons was made in a coal mine at Bernissart, Belgium. These exceptionally preserved specimens revealed that Iguanodon was capable of both bipedal and quadrupedal locomotion, rather than being purely quadrupedal as Mantell and Owen had envisioned. The famous “horn” that Mantell had placed on the creature’s nose was revealed to be a modified thumb spike, likely used for defense or feeding. Modern paleontologists recognize Iguanodon as a large ornithopod dinosaur that lived during the Early Cretaceous period, approximately 125 million years ago. While our scientific understanding of this dinosaur has evolved substantially, the fundamental importance of Mantell’s pioneering work in identifying the first herbivorous dinosaur remains unchanged.

Reassessing Mantell’s Place in Science

In recent decades, historians of science have undertaken a significant reassessment of Mantell’s contributions, elevating his status from that of a fortunate amateur to a legitimate founding figure in dinosaur paleontology. Modern scholarship has recognized how Mantell’s meticulous approach to collecting and documenting fossils established important methodological precedents for the field. His careful attention to geological context, detailed record-keeping, and efforts to reconstruct prehistoric environments were well ahead of their time. While Richard Owen may have coined the term “dinosaur” and dominated British paleontology during the Victorian era, contemporary historians acknowledge that Mantell’s contributions were equally foundational. The rediscovery of Mantell’s extensive personal diaries and correspondence has provided valuable insights into not only his scientific methodology but also the social dynamics of early 19th-century science, painting a more complete picture of how a provincial doctor overcame significant class barriers to make lasting contributions to scientific knowledge.

Conclusion

Gideon Mantell’s remarkable journey from country doctor to pioneering paleontologist exemplifies the power of curiosity, perseverance, and methodical investigation. Despite lacking formal scientific training, facing opposition from established scientists, and enduring personal tragedy and physical suffering, Mantell’s passionate pursuit of knowledge led to discoveries that fundamentally transformed our understanding of Earth’s prehistoric past. His identification of Iguanodon opened a window into an ancient world populated by creatures previously unimagined, helping to establish dinosaur paleontology as a scientific discipline. Though aspects of his work have been superseded by later discoveries, Mantell’s legacy as one of the founding figures of dinosaur science remains secure. His story continues to inspire amateur scientists and fossil enthusiasts, demonstrating that groundbreaking contributions to knowledge can come from unexpected sources when driven by genuine passion and careful observation.