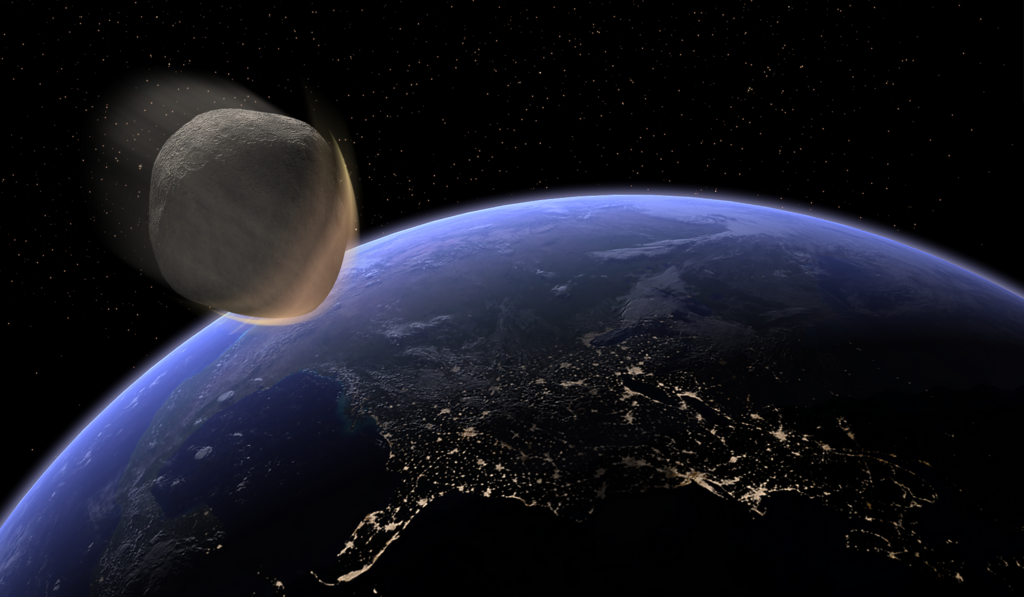

When you think about catastrophic events in Earth’s history, few match the raw, apocalyptic devastation that unfolded 66 million years ago when an asteroid, about ten kilometers (six miles) in diameter, struck Earth. This wasn’t just any cosmic collision – it was the event that ended the age of dinosaurs and reshaped life on our planet forever. But what exactly happened during those first crucial 24 hours after impact? Recent scientific discoveries are painting an increasingly detailed and terrifying picture of that momentous day.

The Moment of Impact: A Cosmic Bullet Hits Earth

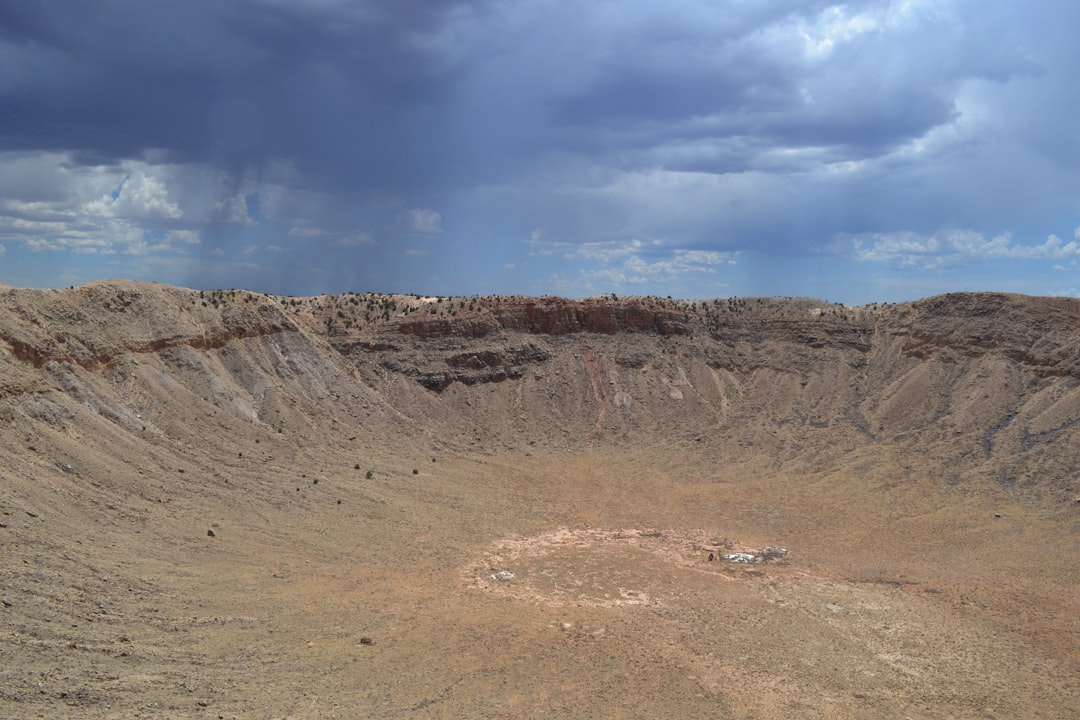

Picture this: The asteroid hit at an estimated speed of 20 kilometers per second (more than 58 times the speed of sound) at a relatively steep angle of between 45 and 60 degrees to the Earth’s surface. The impact site, now known as the Chicxulub crater, sits underneath the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. Its center is offshore, but the crater is named after the onshore community of Chicxulub Pueblo.

The sheer force of this collision was beyond imagination. The impact produced as much explosive energy as 100 teratons of TNT, 4.5 billion times the explosive power of the Hiroshima atomic bomb. Within seconds, the asteroid had hit at high velocity and effectively vaporized. It made a huge crater, so in the immediate area there was total devastation.

The resulting crater was enormous. The crater is estimated to be 200 kilometers (120 miles) in diameter and 30 kilometers (19 miles) in depth, making it one of the largest impact structures on Earth.

The First Minutes: A Wall of Water and Rock

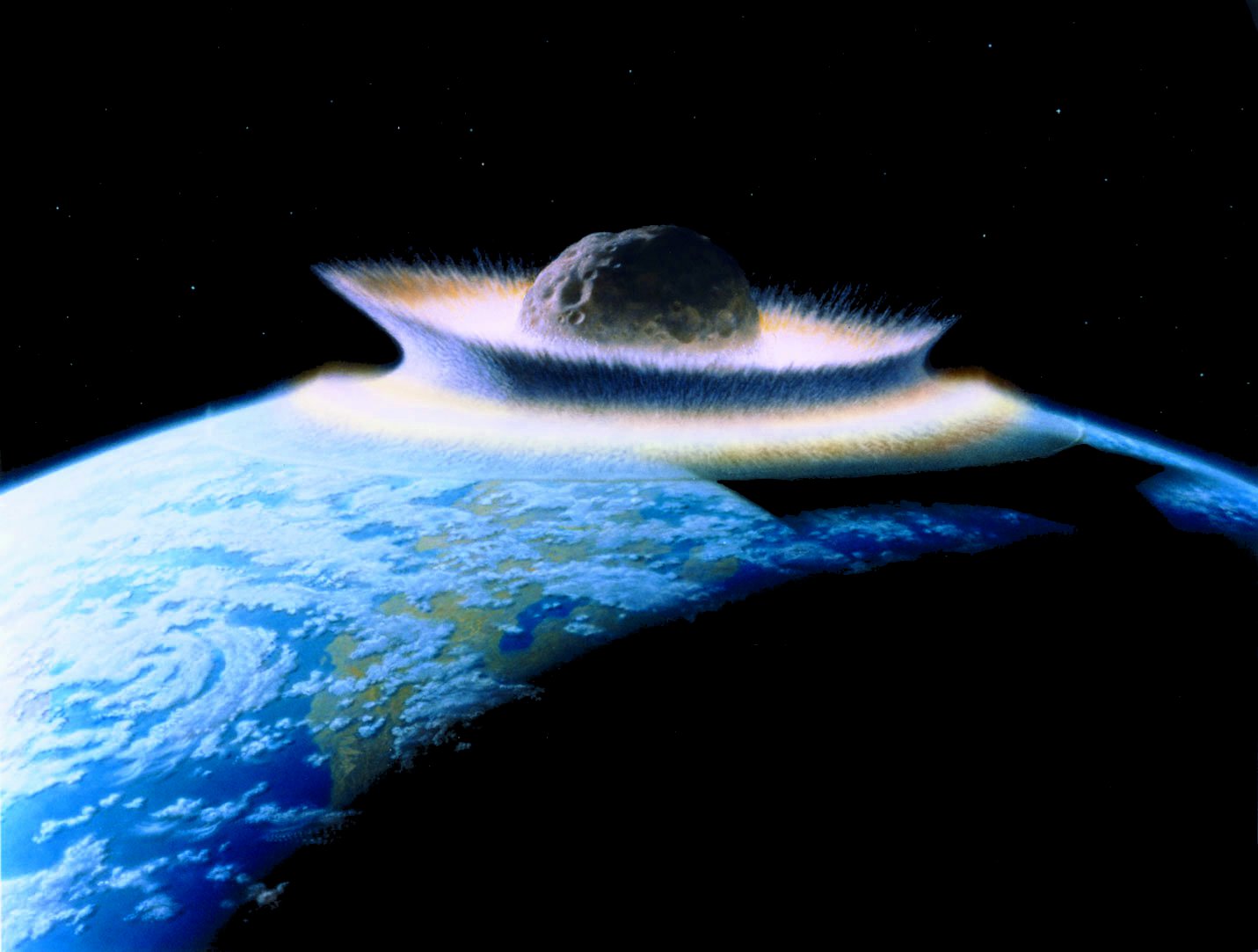

What happened in those first precious minutes was nothing short of apocalyptic. Two and a half minutes after the asteroid struck, a curtain of ejected material pushed a wall of water outward from the impact site, briefly forming a 4.5-kilometer-high (2.8-mile-high) wave that subsided as the ejecta fell back to Earth. Just imagine – a wave nearly three miles tall racing outward from the impact zone.

Within minutes of the asteroid strike, Gulick and colleagues found, the underlying rock at the site collapsed and formed a crater with a peak ring. The ring was soon covered by over 70 feet of additional rock that had melted in the heat of the blast. The devastation was instantaneous and complete in the immediate vicinity.

Ten minutes after the projectile hit the Yucatan, and 220 kilometers (137 miles) from the point of impact, a 1.5 kilometers high (0.93 miles) tsunami wave – ring-shaped and outward-propagating – began sweeping across the ocean in all directions.

Vaporized Rock and Molten Rain

The impact launched an incredible amount of material into the atmosphere. When the asteroid plowed into the Earth, tiny particles of rock and other debris were shot high into the air. Geologists have found these bits, called spherules, in a 1/10-inch-thick layer all around the world. These weren’t just ordinary particles – they carried tremendous energy.

The kinetic energy carried by these spherules is colossal, about 20 million megatons total or about the energy of a one megaton hydrogen bomb at six kilometer intervals around the planet. As these spherules began their deadly descent roughly 40 minutes after impact, they transformed the atmosphere itself into a weapon.

All of that energy was converted to heat as those spherules started to descend through the atmosphere 40 miles up, about 40 minutes after impact. Earth became a world on fire. The friction of falling made each spherule an incandescent torch that quickly and dramatically heated the atmosphere.

Global Wildfires Ignite Across Continents

The superheated debris raining down from the sky had a catastrophic effect on life below. Any creature not underground or not underwater – that is, most dinosaurs and many other terrestrial organisms – could not have escaped it. Animals caught out in the open may have died directly from several sustained hours of intense heat, and the unrelenting blast was enough in some places to ignite dried-out vegetation that set wildfires raging.

These weren’t small, localized fires. This, they say, is evidence of huge wildfires that would have stretched for hundreds and hundreds of miles. The scale was truly global. However, the remainder would have rained down over North America, incinerating everything within a radius of more than 1,000 miles and causing wildfires in 70% of the world’s forests.

The evidence for these massive fires is preserved in the rock record. Within this layer was charcoal, the researchers discovered, providing clear geological proof of the worldwide conflagration that followed the impact.

The Birth of a Monster Tsunami

While fires raged on land, the oceans were experiencing their own form of chaos. The tsunami generated by the impact was unlike anything in recorded history. Researchers estimate that the tsunami was up to 30,000 times more energetic than the December 26, 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, one of the largest on record, that killed more than 230,000 people.

The waves didn’t just affect the immediate area. An hour after impact, the tsunami had travel beyond the Gulf of Mexico into the North Atlantic Ocean. The speed and reach of these waves was extraordinary, traveling at velocities comparable to modern aircraft.

Sean Gulick, lead author of the latest paper, said the wave would have been at least hundreds of meters high – and that it was traveling around the speed of a jet plane. The power was so immense that the tsunami was powerful enough to create towering waves more than a mile high and scour the ocean floor thousands of miles away from where the asteroid hit.

Four Hours Later: Crossing Into the Pacific

As the hours ticked by, the tsunami’s global reach became apparent. Four hours post-impact, the waves passed through the Central American Seaway and into the Pacific Ocean. This ancient seaway, which once separated North and South America, provided a crucial pathway for the destructive waves to spread.

The modeling studies show just how comprehensive this oceanic devastation was. Four hours after impact, the waves had passed through the Central American Seaway and into the Pacific, carrying their destructive energy across vast distances.

The tsunami wasn’t just about height – it was about raw, erosive power. In those basins and in some adjacent areas, underwater current speeds likely exceeded 20 centimeters per second (0.4 mph), a velocity that is strong enough to erode fine-grained sediments on the seafloor. This doesn’t sound like much, but it was enough to reshape ocean floors thousands of miles away.

Earthquakes and Secondary Disasters

The impact didn’t just create immediate destruction – it triggered a cascade of secondary disasters. The blast was enough to cause geologic disturbances, such as earthquakes and landslides, as far away as Argentina – which in turn created their own tsunamis. The shockwaves from the impact literally shook the entire planet.

In addition to spawning massive earthquakes at the impact site (of a magnitude between 9 and 11), the shockwave from the asteroid triggered earthquakes and volcanic activity around the world. To put this in perspective, the most powerful earthquake ever recorded by instruments was magnitude 9.5 in Chile in 1960. The Chicxulub impact created earthquakes potentially even more powerful than that.

The sea battered against the new hole in the planet, and in the minutes and hours that followed, surges of water rushing back into the crater carried laid down more than 260 additional feet of melted stone atop the already accumulated rock.

The Atmosphere Turns Deadly

While the ground shook and waters roared, the atmosphere itself was becoming toxic. The team also found an absence of sulfur in the deposits – which is unusual as the area is known for having sulfur-rich rocks. This indicates the impact caused a reaction leading to the release of sulfate aerosols – which caused the long period of darkness and global cooling.

The atmospheric effects were immediate and devastating. Calculations of impact debris raining from space back through the atmosphere suggests that debris shock-heated the atmosphere, driving chemical reactions that generated nitric acid rain. Additional nitric acid rain may have also been produced by impact-generated wildfires.

The dust and sulfurous materials ejected into the atmosphere would have led to a nuclear winter-like effect, with a rapid decrease in global temperatures (as sulfate aerosols have a cooling effect in the upper atmosphere) and acid rain (with the sulfates and water vapor combining to form sulfuric acid).

Twenty-Four Hours: A Global Ocean of Destruction

By the time Earth had completed one full rotation since the impact, the tsunami had become a truly global phenomenon. Within 24 hours, the waves entered the Indian Ocean from both sides after traveling across the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. This meant that virtually no coastline on Earth was safe from the destruction.

Twenty-four hours after impact, the waves had crossed most of the Pacific from the east and most of the Atlantic from the west and entered the Indian Ocean from both sides. The scale was unprecedented in human experience.

Depending on the geometries of the coast and the advancing waves, most coastal regions would be inundated and eroded to some extent. The geological evidence supports this global reach, with it effectively wiped away the sediment record of what happened before the event, as well as during it. “This tsunami was strong enough to disturb and erode sediments in ocean basins halfway around the globe, leaving either a gap in the sedimentary records or a jumble of older sediments”.

The Beginning of Nuclear Winter

As the first day drew to a close, perhaps the most ominous effects were just beginning. Tremendous amounts of soot, lofted into the air from global wildfires following a massive asteroid strike 66 million years ago, would have plunged Earth into darkness for nearly two years. The immediate fires and heat were just the beginning of a much longer nightmare.

In the simulations, soot heated by the Sun was lofted higher and higher into the atmosphere, eventually forming a global barrier that blocked the vast majority of sunlight from reaching Earth’s surface. At first it would have been about as dark as a moonlit night, but this darkness would persist for months or even years.

Calculations of an atmosphere choked with dust and sulphate aerosols from the impact event, and soot from post-impact wildfires, suggest surface temperatures fell and sunlight was unable to reach the Earth’s surface, shutting down photosynthesis. These calculations are consistent with the fossil record, which indicates the base of the marine food chain, composed of photosynthetic plankton, collapsed.

The Day That Changed Everything

As that first 24-hour period ended, Earth was utterly transformed. These events account for the loss of 75 percent of known species at the end of the Cretaceous. What had begun as a normal day in the Cretaceous period had become the beginning of one of the most severe mass extinctions in Earth’s history.

On land, at least, much of Cretaceous life may have been wiped out in a matter of hours. The heat pulse and its after-effects alone severely winnowed back life’s diversity. The survivors were those lucky enough to be underground, underwater, or somehow shielded from the initial onslaught of heat and debris.

We interpret this section to represent the first day post impact, which by the definition of the geologic time scale, makes it the first day of the Cenozoic since the Cretaceous ended the moment the asteroid struck. In geological terms, this single day marked the boundary between two entire eras of Earth’s history.

The evidence for this catastrophic day is preserved in rock layers around the world, telling the story of the events from the first minutes until a few hours after the impact of the giant Chicxulub asteroid in extreme detail.

Conclusion: When Worlds End in a Day

The first 24 hours after the dinosaur-killing asteroid struck Earth represent one of the most catastrophic periods in our planet’s history. From the initial vaporizing impact to the global tsunami that followed, from worldwide wildfires to the beginning of a years-long nuclear winter, this single day compressed geological ages of change into mere hours.

The scale of destruction was almost incomprehensible. Within minutes, a three-mile-high wall of water was racing away from the impact site. Within hours, tsunamis were crossing oceans and wildfires were consuming continents. Within a day, the very atmosphere had become toxic and dark.

Yet life survived. Hidden in burrows, sheltered underwater, or simply lucky enough to avoid the worst of the initial catastrophe, some species endured. These survivors would inherit a radically changed world and eventually give rise to the mammals – and ultimately, to us.

When you look up at the night sky and see asteroids as distant points of light, remember that 66 million years ago, one of those cosmic wanderers rewrote the entire story of life on Earth in just 24 hours. Makes you wonder what a difference a day can make, doesn’t it?