In the late 19th century, as America pushed westward and scientific discovery flourished, two paleontologists embarked on one of the most notorious scientific feuds in history. Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope, once colleagues with a shared passion for uncovering prehistoric mysteries, became bitter rivals in what would later be known as the “Bone Wars.” Their decades-long competition transformed our understanding of prehistoric life while simultaneously descending into sabotage, theft, and public humiliation. This scientific rivalry uncovered thousands of fossils and identified hundreds of new species, fundamentally changing our understanding of dinosaurs and prehistoric life, but at what cost?

The Origins of the Rivalry

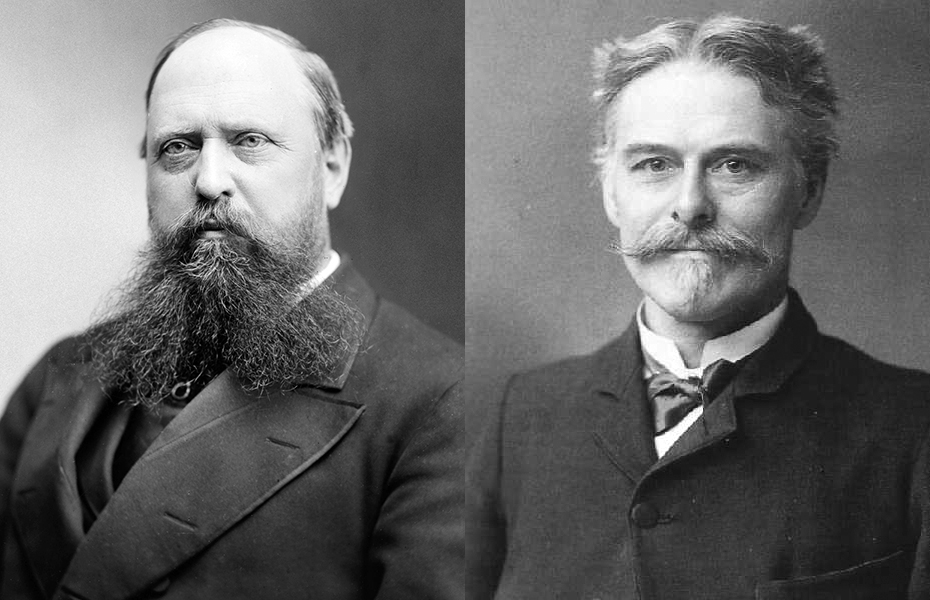

The seeds of animosity between Marsh and Cope were planted in the late 1860s when both men were still on friendly terms. Edward Drinker Cope, born to a wealthy Quaker family in Philadelphia, was largely self-taught but had already established himself as a prodigious scientist by his early twenties. Othniel Charles Marsh, nephew of wealthy philanthropist George Peabody, pursued formal education later in life, eventually becoming the first professor of paleontology at Yale University. Their initial friendship included cordial visits to each other’s fossil-hunting grounds and exchanges of specimens and information. The relationship began to sour around 1868 when Marsh allegedly paid Cope’s fossil collectors to send their discoveries to him instead. Adding further insult, Marsh publicly humiliated Cope by pointing out that Cope had mounted the head of an Elasmosaurus on the wrong end of the skeleton—an error that haunted Cope’s professional reputation for years to come.

Intellectual Backgrounds and Approaches

The two paleontologists came from markedly different intellectual traditions, which influenced their scientific approaches. Cope, despite lacking formal higher education, was a prolific naturalist who published over 1,400 papers in his lifetime. His approach was holistic and intuitive, often making quick identifications and publishing rapidly to establish priority. Marsh, by contrast, was methodical and cautious, benefitting from his formal training at Yale and later in Germany, where he studied under some of Europe’s most distinguished scientists. Marsh preferred to collect specimens extensively before concluding, sometimes delaying publication for years until he was certain of his findings. These contrasting scientific methodologies—Cope’s rapid publication versus Marsh’s deliberate accumulation of evidence—mirrored their personalities and contributed to their competitive tension. Cope believed in Neo-Lamarckism, which held that acquired characteristics could be inherited, while Marsh was an early supporter of Darwin’s theory of evolution.

The Financial Dimensions of the Feud

Money played a crucial role in fueling the Bone Wars, with both men willing to expend vast fortunes in their quest for paleontological dominance. Marsh enjoyed institutional backing from Yale and financial support from his wealthy uncle, George Peabody, who funded the Peabody Museum of Natural History, where many of Marsh’s discoveries were housed. Cope initially relied on his family’s substantial wealth, eventually spending his entire inheritance on fossil expeditions and publications. As their competition intensified, both men hired small armies of fossil hunters, paying top dollar for exclusive rights to promising dig sites across the American West. The financial strain eventually took its toll on Cope, who was forced to sell much of his fossil collection in his later years to support himself. By the 1880s, Cope had nearly bankrupted himself through fossil-hunting expenses, while Marsh continued to benefit from institutional support. The economic Panic of 1873 particularly affected Cope’s investments, leaving him financially vulnerable while Marsh maintained relatively stable funding.

The Western Frontier as Battleground

The American West provided the perfect theater for the Bone Wars, with its newly accessible territories rich in fossil deposits. As the Transcontinental Railroad opened up the western territories in the late 1860s, both paleontologists recognized the scientific potential of these previously unexplored regions. Colorado, Wyoming, Nebraska, and the Dakota Territories became the primary battlegrounds for their competing expeditions. Como Bluff in Wyoming proved particularly rich in Jurassic fossils, becoming one of the most contested sites between the rivals. Local settlers and railroad workers often became impromptu fossil hunters, alerting Cope or Marsh to discoveries in exchange for payment. The harsh frontier conditions added additional challenges—extreme weather, hostile Native American tribes protecting their territories, and the logistical difficulties of extracting and transporting massive fossils across rugged terrain. Despite these obstacles, the scientists’ determination drove them to establish elaborate networks of collectors and informants throughout the West, transforming paleontological fieldwork from an occasional expedition to a continuous industrial-scale operation.

Espionage and Sabotage Tactics

As their rivalry intensified, both Marsh and Cope resorted to increasingly underhanded tactics to undermine each other’s work. Fossil sites were routinely sabotaged, with workers hired to destroy remaining bones after extracting the best specimens to prevent rivals from making additional discoveries. Both men employed spies within each other’s camps, bribing workers to redirect valuable fossils or provide intelligence about new fossil locations. Mail was intercepted, specimens were stolen in transit, and dig sites were guarded by armed men to prevent interference. In one famous incident, Marsh’s team reportedly dynamited a site rather than leave it for Cope’s collectors to explore. The two men even resorted to creating elaborate false trails and spreading misinformation about fossil locations to waste each other’s time and resources. These tactics spread beyond the field and into the scientific community, where both men attempted to block the other’s publications, appointments, and access to grants, bringing their animosity into the professional sphere in ways that damaged the integrity of American paleontology.

The Publishing War

The competition between Marsh and Cope played out dramatically in scientific publications, where both men raced to describe new species and claim priority. The pressure to publish first led to hasty work, with Cope sometimes writing descriptions of new species by lamplight at his field camp to rush them into print. Marsh, with his institutional position at Yale, often had better access to scientific journals and used this advantage to delay or block Cope’s submissions while expediting his own. The volume of their output was staggering—Cope published nearly 1,400 papers in his lifetime, while Marsh produced fewer but often more comprehensive works. They frequently published papers specifically designed to refute each other’s findings, pointing out errors and inconsistencies with barely concealed contempt. The scientific literature became a battleground where taxonomy and classification were weapons wielded for personal vendetta rather than scientific advancement. This publishing war ultimately damaged both men’s scientific legacy, as later researchers discovered numerous errors, duplicate namings, and misclassifications resulting from their haste to claim priority over discoveries.

Major Dinosaur Discoveries

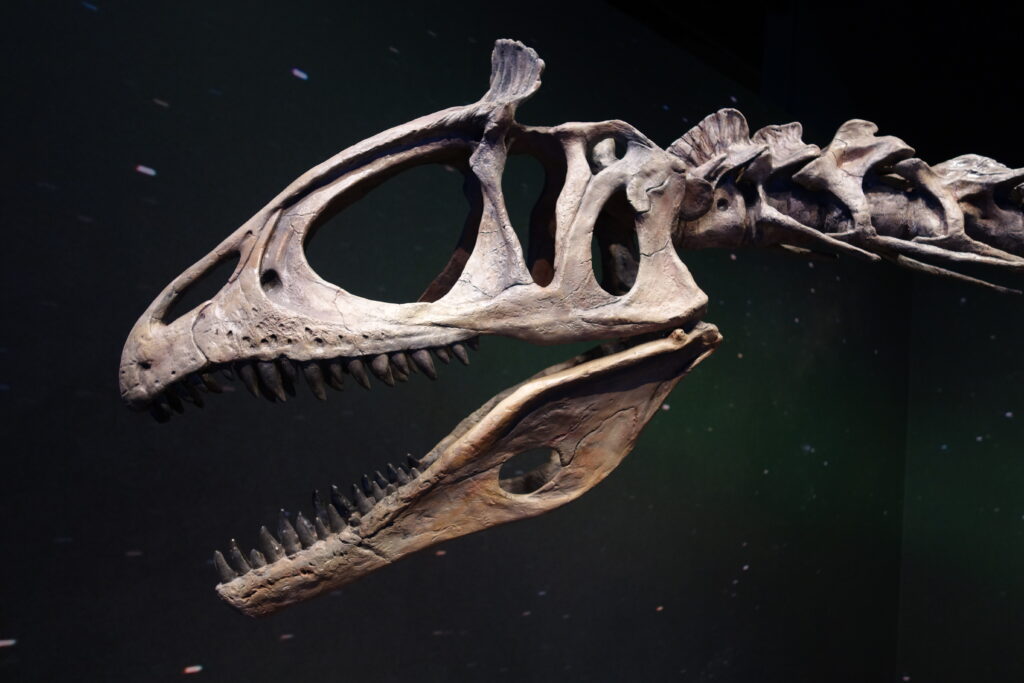

Despite the unseemly nature of their competition, the Bone Wars yielded an extraordinary number of important paleontological discoveries that revolutionized our understanding of prehistoric life. Marsh described and named iconic dinosaurs, including Stegosaurus, Triceratops, Apatosaurus (then called Brontosaurus), and Allosaurus—species that would become household names and fundamentally shape public perception of the dinosaur age. Cope countered with discoveries like Camarasaurus, Coelophysis, and Monoclonius, along with numerous important fossil mammals and marine reptiles. Together, they identified more than 136 new species of dinosaurs during an era when dinosaur paleontology was in its infancy. Their discoveries extended beyond dinosaurs to include prehistoric mammals, birds, and marine reptiles, creating a much more complete picture of North America’s prehistoric fauna. These fossil discoveries came at an astonishing rate—in some years, new species were being named weekly, an unprecedented pace of paleontological identification that has never been matched since. The sheer volume of material they unearthed continues to provide valuable research specimens for modern paleontologists, with some specimens still awaiting proper study more than a century later.

Scientific Errors and Hasty Conclusions

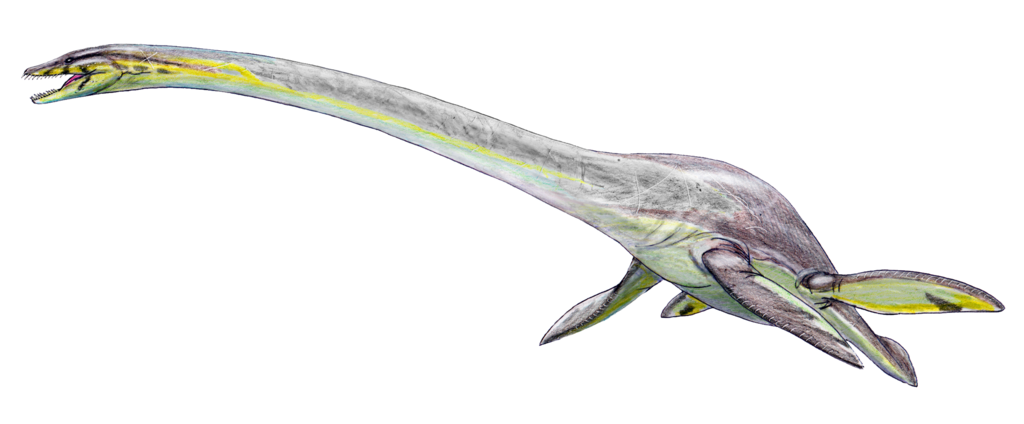

The frantic pace of discovery and the pressure to publish first led both Marsh and Cope to make significant scientific errors that later required correction. Perhaps most infamously, Cope’s incorrect reconstruction of Elasmosaurus with its head placed on its tail rather than its neck became a lasting embarrassment when Marsh publicly pointed out the error. Marsh himself was not immune to mistakes, incorrectly assembling the skull of Apatosaurus and creating taxonomic confusion that persisted for decades. Both men frequently identified “new” species based on fragments that were later determined to belong to already-named dinosaurs, creating a taxonomic tangle that paleontologists are still working to unravel. The pressure of competition led to instances where immature specimens were classified as distinct species rather than juvenile forms of known dinosaurs. Cope’s adherence to Neo-Lamarckian evolutionary theory, which was falling out of scientific favor, also affected his interpretations of fossil evidence and led to some erroneous conclusions about evolutionary relationships. The rush to publish meant that many specimens were never fully prepared or properly documented, creating headaches for later researchers attempting to study this material systematically.

Personal Animosity and Character Assassination

Beyond scientific disagreements, the feud between Marsh and Cope descended into vicious personal attacks that damaged both men’s reputations. Cope frequently criticized Marsh’s privileged background and connections, suggesting he had achieved his position through nepotism rather than merit. Marsh, in turn, used his influence with government officials to undermine Cope’s standing and access to research sites. Their correspondence with other scientists often included scathing assessments of each other’s character and competence, poisoning the broader scientific community against their rival. By the 1880s, their animosity had become public knowledge through newspaper articles that delighted in reporting the unseemly scientific feud. Cope kept a journal documenting what he perceived as Marsh’s ethical lapses and scientific errors, intending to publish it as a comprehensive takedown of his rival’s career. The conflict reached its nadir when Cope, in failing health, allegedly challenged Marsh to resolve their dispute by comparing their brain sizes after death, offering his brain for posthumous measurement and suggesting that the larger brain would vindicate the superior scientist. This macabre proposal epitomized how deeply personal their scientific rivalry had become.

The Government Surveys Controversy

The rivalry between Marsh and Cope extended into the political realm through their connections to competing government-sponsored western surveys in the 1870s. Cope aligned himself with Ferdinand V. Hayden’s U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories, serving as its vertebrate paleontologist while receiving federal funding for his research. Marsh, meanwhile, cultivated a close relationship with John Wesley Powell, director of the U.S. Geological Survey, eventually securing appointment as the survey’s official paleontologist in 1882 after the various competing surveys were consolidated. This consolidation proved disastrous for Cope, who lost his government position and funding, while Marsh gained nearly exclusive access to fossils discovered on federal lands. Frustrated by this situation, Cope launched a public campaign against Marsh and Powell, publishing accusations of mismanagement and corruption in the New York Herald in 1890. This explosive series of articles, which Marsh attempted to counter with his defenses, brought their private feud fully into the public eye and damaged the reputation of American science. The scandal eventually led to congressional hearings and contributed to Powell losing much of his survey funding, but by then, both paleontologists had suffered irreparable damage to their public standing.

The Scientific Legacy of the Bone Wars

Despite the ethical shortcomings and personal animosity that characterized the Bone Wars, the scientific impact of Marsh and Cope’s work was transformative for paleontology. Together, they discovered and described more than 136 new dinosaur species, effectively creating the foundation of North American vertebrate paleontology. Their discoveries dramatically expanded scientific understanding of prehistoric life during a crucial period when evolutionary theory was still being refined and accepted. The massive collections they accumulated—Cope’s eventually going primarily to the American Museum of Natural History and Marsh’s to the Peabody Museum at Yale and the Smithsonian—created research resources that continue to yield new insights today. Their work established the American West as a paleontological treasure trove, shifting the center of dinosaur research from Europe to North America. The techniques they pioneered for extracting, preserving, and mounting large dinosaur fossils influenced museum practices worldwide. Perhaps most significantly, their discoveries captured the public imagination and helped establish dinosaurs as cultural icons, laying the groundwork for the enduring popular fascination with prehistoric life. Modern paleontologists continue to study, reassess, and sometimes correct their work, making the scientific legacy of the Bone Wars an ongoing process of refinement rather than a concluded chapter.

The Final Years and Death

As the nineteenth century drew to a close, both men found their circumstances diminished by their decades of intense competition. Cope, having exhausted his family fortune on fossil collecting and publishing, spent his final years living in reduced circumstances in Philadelphia, surrounded by fossil specimens in his home. Forced to sell much of his prized collection to the American Museum of Natural History for financial survival, he continued working and publishing until his final days. He died in 1897 at age 56, his health likely compromised by years of fieldwork in harsh conditions and the stress of his ongoing battles. Marsh outlived his rival by only two years, dying in 1899 at age 67, having suffered his reversals after the government survey controversy damaged his standing. His position at Yale had been reduced, though he maintained his connections to the Peabody Museum, where his specimens remained. Neither man achieved the complete vindication over his rival that he had sought for decades. In their passing, the scientific community, while acknowledging their enormous contributions, also expressed relief that the destructive feud that had divided American paleontology had finally ended, allowing the field to heal and advance beyond their animosity.

Modern Reassessment and Continuing Impact

Modern paleontologists have undertaken the complex task of reassessing the scientific output of Marsh and Cope, working to untangle the taxonomic confusion created during their hasty naming of species. Digital scanning and modern analytical techniques have allowed researchers to reexamine specimens collected during the Bone Wars, sometimes yielding new insights that neither original collector could have imagined. The ethical lapses of the Bone Wars era have contributed to the development of more rigorous standards in paleontological fieldwork and publication, serving as a cautionary tale in scientific ethics courses. Museums around the world still prominently display dinosaurs discovered during this period, with many of Marsh and Cope’s finds remaining among the most recognizable and beloved prehistoric specimens in public collections. Their story continues to fascinate both scientists and the public, having been chronicled in books, documentaries, and museum exhibitions that explore both their scientific contributions and personal failings. Perhaps most importantly, the foundation they built—despite their flawed methods—accelerated the development of paleontology at a crucial time in its history, creating institutional structures and research traditions that continue to this day. Their legacy remains deeply ambiguous: scientific pioneers whose personal rivalry both advanced and damaged their field, leaving behind both magnificent discoveries and cautionary examples of how not to conduct scientific research.

Conclusion

The Bone Wars between Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope represent a fascinating paradox in scientific history—a bitter personal feud that significantly advanced our understanding of prehistoric life while simultaneously demonstrating the pitfalls of allowing competition to override scientific integrity. Their combined discoveries dramatically expanded the known fossil record, introducing the world to many iconic dinosaur species that continue to captivate public imagination. Yet their legacy is permanently tarnished by their unethical tactics, rushed conclusions, and willingness to sacrifice scientific accuracy for personal victory. Modern paleontology has built upon their discoveries while developing ethical standards specifically designed to prevent the recurrence of such destructive competition. The story of Marsh and Cope serves as both inspiration and warning—a testament to the remarkable achievements possible through dedicated scientific pursuit, and a reminder of how easily such pursuit can be corrupted when prestige and personal animosity take precedence over the collaborative spirit essential to scientific progress.