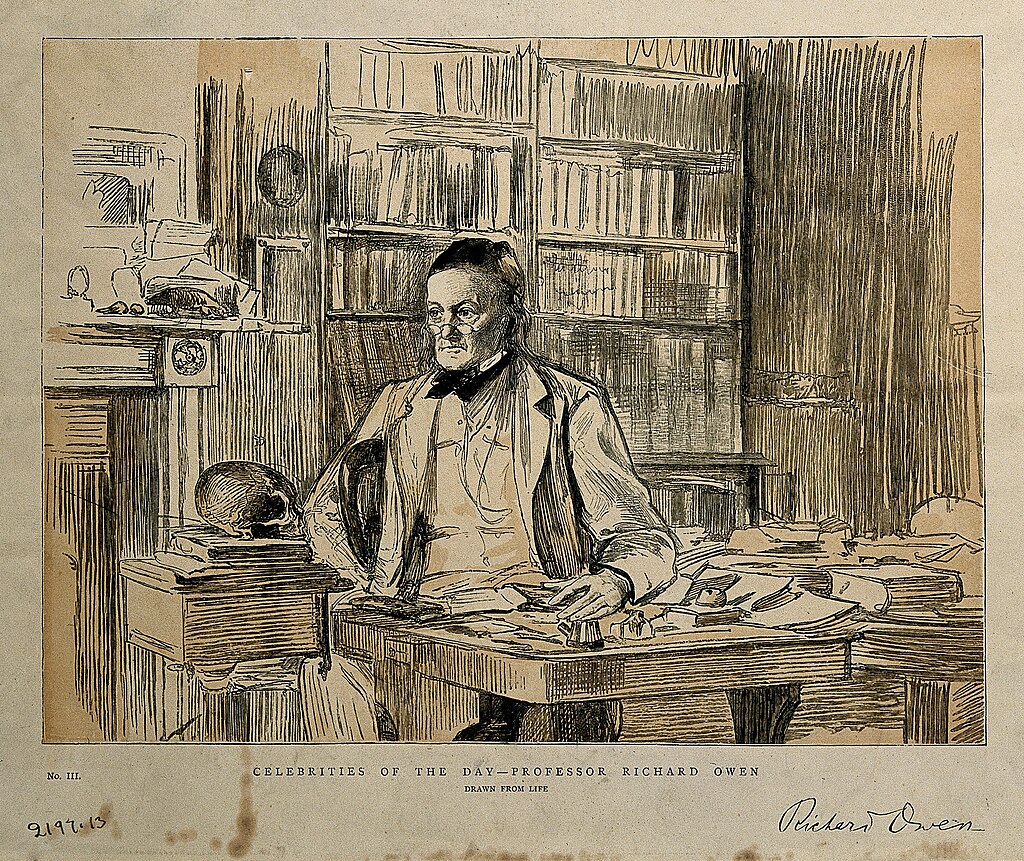

In the grand tapestry of scientific history, few individuals have left such a profound linguistic legacy as Sir Richard Owen. While his name may not command the immediate recognition of Darwin or Einstein, Owen’s contribution to our scientific vocabulary has ensured his immortality in the halls of paleontological fame. In 1842, he introduced the world to a term that would capture humanity’s imagination for centuries to come: “dinosaur.” This taxonomic classification, meaning “terrible lizard,” revolutionized our understanding of prehistoric life and created a framework for comprehending the magnificent creatures that once ruled our planet. Owen’s scientific journey, marked by brilliant insights and fierce rivalries, shaped not only paleontology but also Victorian science as a whole.

Early Life and Education

Born on July 20, 1804, in Lancaster, England, Richard Owen emerged from relatively humble beginnings to become one of the nineteenth century’s most influential scientific figures. After his father’s death when Richard was only five years old, his mother raised him with limited means but a strong emphasis on education. Young Owen displayed an early aptitude for anatomy and natural history, leading him to apprentice with a local surgeon-apothecary at age fourteen. This early medical training laid the groundwork for his later scientific endeavors. In 1825, Owen entered the University of Edinburgh to study medicine, but soon transferred to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, where his exceptional skill in comparative anatomy began to shine. His meticulous approach to dissection and classification would become hallmarks of his later scientific methodology.

Rise to Scientific Prominence

Owen’s career trajectory accelerated dramatically when he became the assistant to John Barclay, a prominent anatomist who recognized the young man’s talents. This connection eventually led to Owen’s appointment at the Royal College of Surgeons in 1827, where he began cataloging the extensive Hunterian Collection of anatomical specimens. His exceptional work caught the attention of influential scientific circles, and by his early thirties, Owen had established himself as a rising star in British natural science. In 1836, he was appointed Hunterian Professor at the Royal College of Surgeons, a prestigious position that provided him with the platform and resources to pursue his ambitious research agenda. During this period, Owen published numerous papers on comparative anatomy, establishing himself as Britain’s preeminent anatomist and setting the stage for his later paleontological breakthroughs.

The Birth of “Dinosaur”

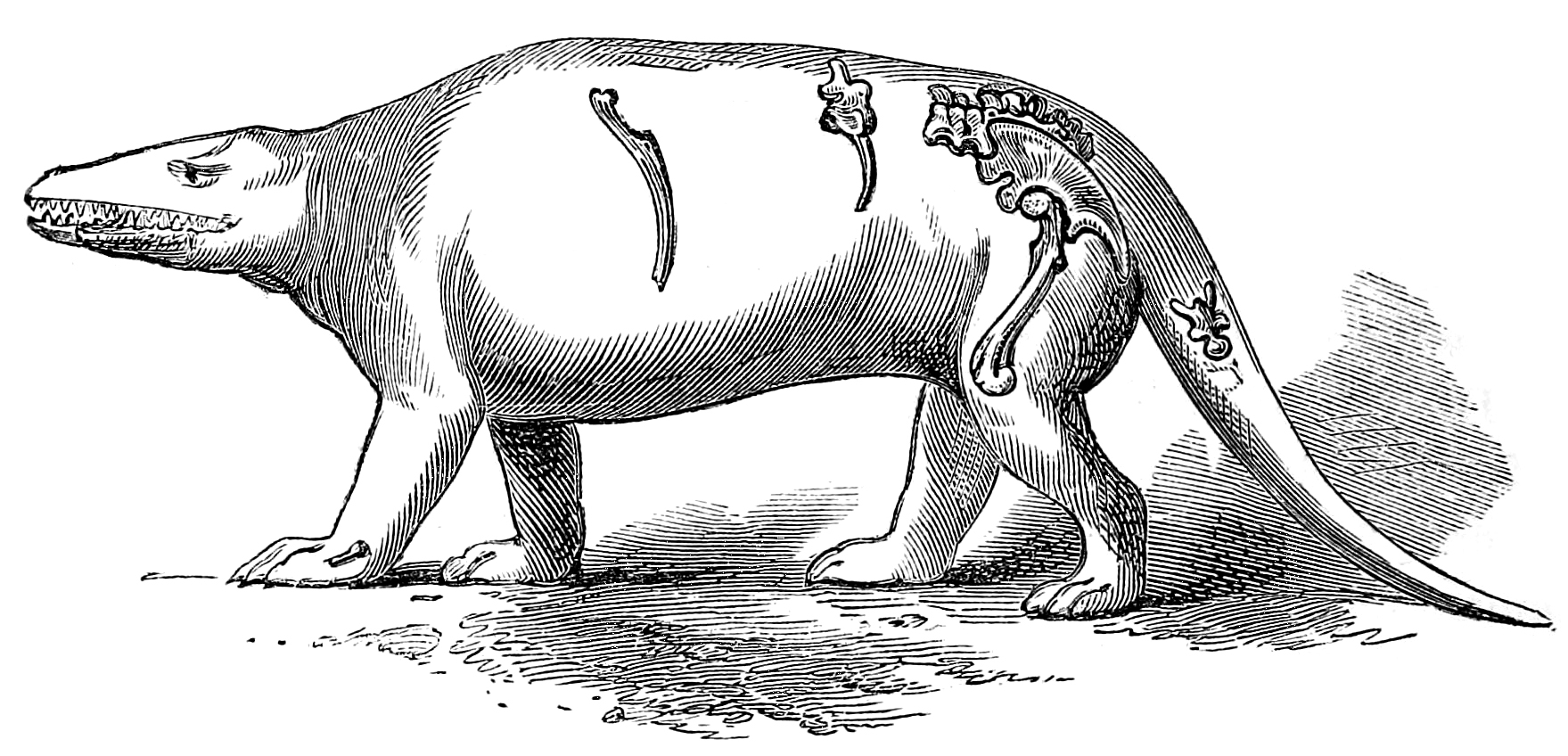

The pivotal moment in Owen’s career came in 1842 during a presentation to the British Association for the Advancement of Science. After studying the fragmentary remains of several large extinct reptiles—specifically Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and Hylaeosaurus—Owen recognized fundamental similarities in their structure that distinguished them from other reptiles. In a stroke of taxonomic brilliance, he coined the term “Dinosauria” (from Greek deinos meaning “terrible, powerful, wondrous” and sauros meaning “lizard”) to classify these creatures as a distinct group. This linguistic innovation did far more than simply name these ancient beasts; it fundamentally altered how scientists and the public conceptualized prehistoric life. Owen’s coinage provided a framework that made these seemingly fantastical creatures comprehensible within the scientific understanding of the time, while simultaneously capturing the public imagination with its evocative imagery.

Owen’s Paleontological Discoveries

Beyond naming dinosaurs, Owen made numerous significant contributions to paleontology through his extensive studies of fossil remains. His detailed descriptions of Megalosaurus and Iguanodon helped establish the fundamental understanding of dinosaur morphology that would guide the field for decades. Owen’s work extended beyond dinosaurs to other extinct creatures as well. His studies of the moa, a giant flightless bird from New Zealand, demonstrated his global approach to paleontology. Perhaps most notably, Owen was the first to identify and describe the Archaeopteryx, a crucial transitional fossil showing features of both reptiles and birds, though he interpreted its significance differently than evolutionists would. His ability to reconstruct entire skeletal structures from fragmentary remains demonstrated a remarkable spatial understanding and anatomical expertise that few contemporaries could match.

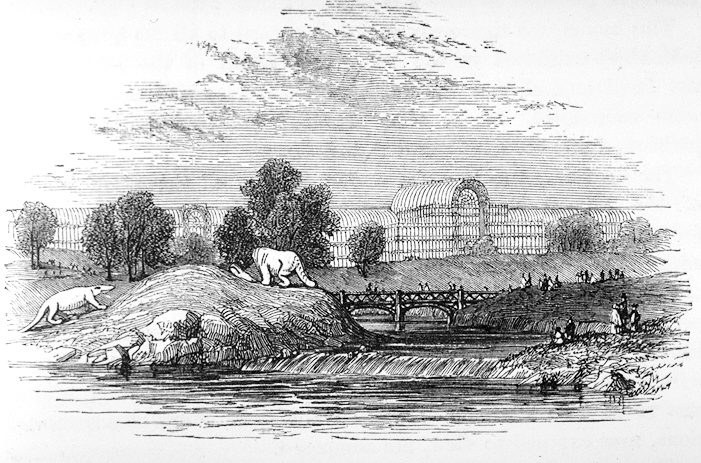

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs

One of Owen’s most enduring public legacies emerged from his collaboration with artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins on the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs in the 1850s. These life-sized concrete sculptures, displayed in London’s Crystal Palace Park, represented the first attempt to create full-scale reconstructions of dinosaurs based on scientific understanding. Owen personally supervised the anatomical details of these models, which, while inaccurate by modern standards, represented the cutting edge of paleontological knowledge at the time. The public unveiling of these sculptures in 1854 caused a sensation, bringing Owen’s dinosaurs into popular culture in an unprecedented way. The famous New Year’s Eve dinner party held inside the partially completed Iguanodon model, with Owen himself reportedly seated at the head of the table, epitomized the Victorian fascination with these prehistoric creatures and cemented Owen’s reputation as the authority on dinosaurs.

Rivalry with Darwin

Perhaps no aspect of Owen’s career has generated more scholarly interest than his complex and often antagonistic relationship with Charles Darwin. Initially, the two scientists maintained cordial professional relations, with Owen even cataloging some of Darwin’s specimens from the Beagle voyage. However, after the publication of “On the Origin of Species” in 1859, Owen emerged as one of Darwin’s most formidable scientific opponents. While Owen accepted the concept of species change over time, he vehemently rejected Darwin’s mechanism of natural selection and the implication that humans descended from ape-like ancestors. Owen’s anonymous, scathing review of Darwin’s work in the Edinburgh Review revealed the depths of his opposition. This rivalry was not merely academic but reflected fundamentally different worldviews about nature’s organization and humanity’s place within it, with Owen advocating for a more divinely ordered system that maintained human exceptionalism.

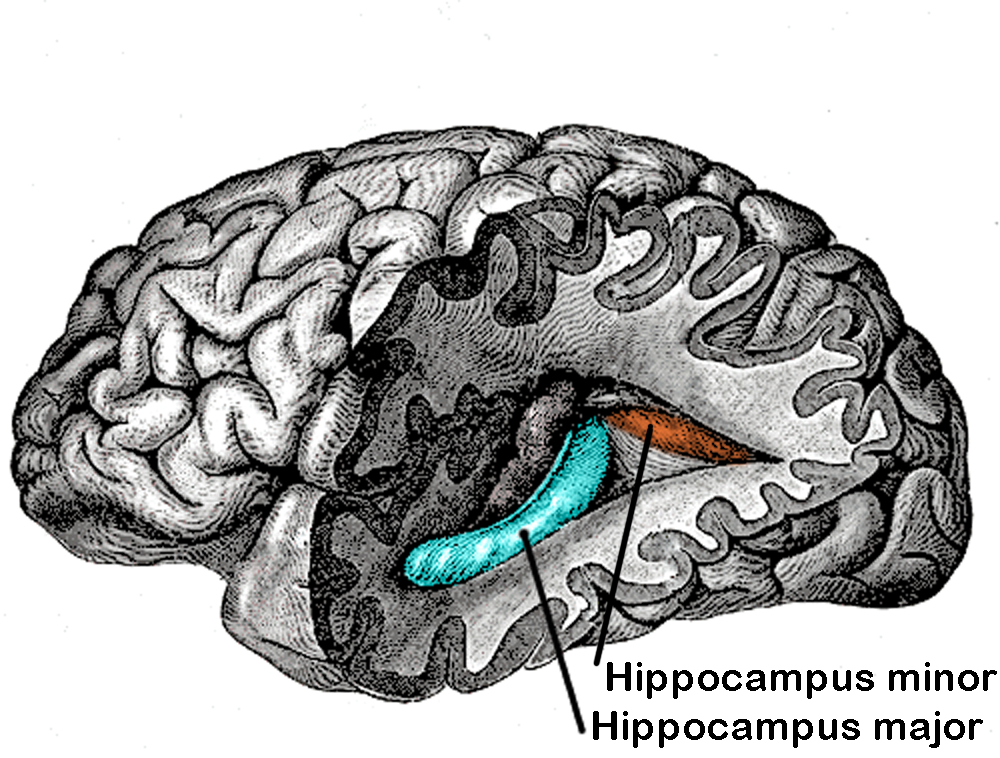

Owen’s Anatomical Contributions

Beyond his paleontological work, Owen made substantial contributions to comparative anatomy that influenced scientific understanding across multiple disciplines. He conducted pioneering research on the anatomy of numerous animal groups, from marsupials to primates, establishing important classifications that in many cases remain valid today. His concept of “homology”—the idea that structural similarities between different species indicate common ancestry—provided a fundamental principle for comparative anatomy, ironically later used by evolutionists to support their theories. Owen’s detailed studies of primate anatomy, particularly his work on gorilla specimens, represented some of the first scientific descriptions of these animals. His controversial claim regarding the “hippocampus minor” (a brain structure he incorrectly claimed was uniquely human) sparked the notorious “hippocampus question” debate with Thomas Henry Huxley, further exemplifying how anatomical questions became battlegrounds for larger theoretical disputes in Victorian science.

Founding the Natural History Museum

One of Owen’s most tangible and enduring achievements was his central role in establishing London’s Natural History Museum. For decades, Owen campaigned tirelessly for a dedicated natural history museum, separate from the British Museum, that could properly house and display the nation’s growing scientific collections. His persistence finally paid off when construction began in 1873 on the magnificent Romanesque building in South Kensington that still houses the museum today. Owen served as the institution’s first director, meticulously overseeing its development as a temple to natural science. His vision for the museum emphasized public education alongside scientific research, establishing a model for natural history museums worldwide. The museum’s iconic central hall, with its imposing Diplodocus skeleton (added after Owen’s time), stands as a fitting monument to the man who gave dinosaurs their name.

Scientific Legacy and Controversies

Owen’s scientific legacy remains a study in contrasts, with his undeniable contributions to anatomy and paleontology set against a backdrop of controversial practices and theoretical missteps. His resistance to Darwinian evolution, while scientifically misguided, reflected complex philosophical positions rather than simple religious dogmatism. Owen’s theoretical framework of “archetypes”—ideal forms underlying anatomical structures—represented a sophisticated if ultimately incorrect approach to explaining biological diversity. More problematically, Owen developed a reputation for failing to properly credit the work of colleagues and sometimes claiming others’ discoveries as his own. The most notorious example involved his treatment of Gideon Mantell, the discoverer of Iguanodon, whose contributions Owen repeatedly minimized. These ethical controversies have complicated assessments of Owen’s scientific legacy, creating a historical portrait of a brilliant but deeply flawed scientific figure whose ambition sometimes overcame his professional ethics.

Owen’s Writing and Communication Style

Richard Owen possessed a distinctive communication style that both advanced and occasionally hindered the spread of his scientific ideas. His writing was characterized by precise technical language that demonstrated his mastery of anatomy but could make his work challenging for non-specialists to comprehend. Unlike some of his contemporaries who embraced more accessible prose styles, Owen often employed dense terminology and complex sentence structures that reinforced his authority but limited his readership. In public lectures, however, Owen could display remarkable clarity and even theatrical flair, particularly when discussing his dinosaur discoveries. His skill in communicating with influential patrons, including Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, proved crucial to securing support for his scientific initiatives. Owen’s ability to navigate both specialized scientific discourse and aristocratic patronage networks reflected his social adeptness in Victorian society and helped establish the professional infrastructure for natural science in Britain.

Personal Life and Character

Behind the public figure of scientific authority, Owen’s personal life reveals a more complex individual. In 1835, he married Caroline Clift, the daughter of his mentor William Clift, establishing both personal and professional connections that advanced his career. Their marriage produced one son, William Owen, but was marked by Caroline’s recurring health problems. Contemporary accounts describe Owen as brilliant but difficult—capable of charm when necessary but also prone to holding grudges and engaging in petty disputes. His home in Richmond Park served as both a domestic refuge and a working laboratory, where he conducted dissections and hosted scientific colleagues. Despite his sometimes combative professional relationships, Owen maintained a steady domestic life that provided stability throughout his tumultuous career. His personal correspondence reveals a man deeply committed to his scientific work, sometimes at the expense of broader social relationships, embodying the emerging archetype of the dedicated professional scientist in Victorian Britain.

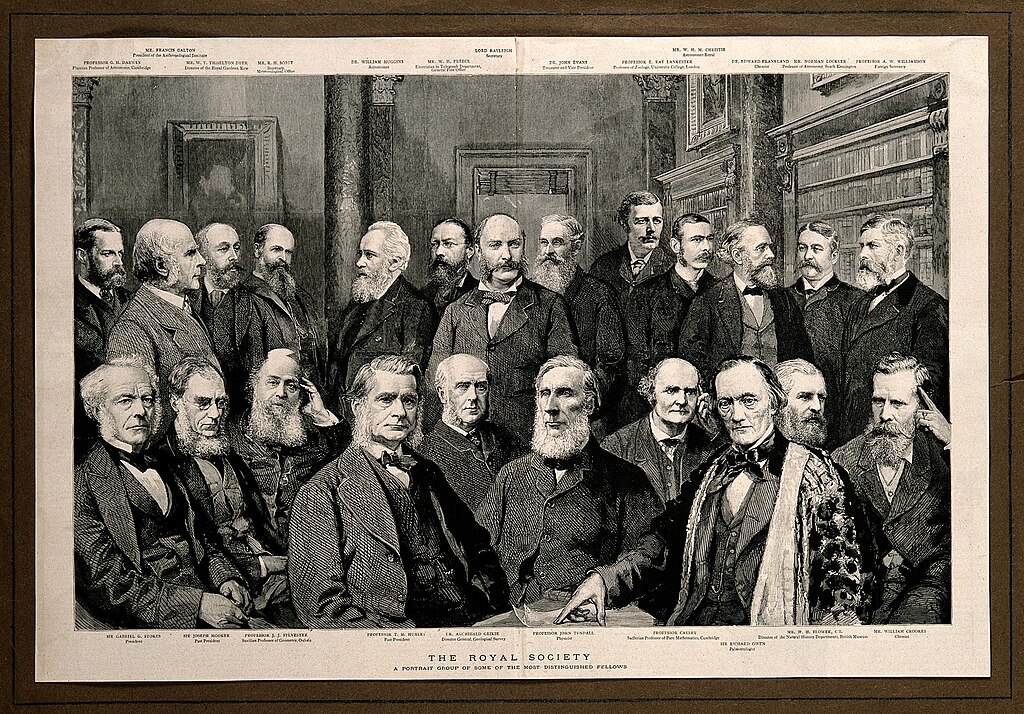

Honors and Recognition

Throughout his long career, Owen received numerous accolades recognizing his scientific contributions. In 1884, he was knighted by Queen Victoria, becoming Sir Richard Owen in recognition of his services to science. The Royal Society awarded him their prestigious Royal Medal twice (in 1842 and 1846) and the Copley Medal in 1851, acknowledging his anatomical and paleontological research. International recognition came in the form of honorary memberships in scientific societies across Europe and America, establishing him as a truly global scientific figure. The Geological Society of London awarded him the Wollaston Medal, their highest honor, in 1838 for his pioneering work on fossil reptiles. These formal honors were complemented by his appointment to prestigious positions, including Hunterian Professor at the Royal College of Surgeons and later Superintendent of the Natural History Departments of the British Museum, positions that provided both status and resources for his continued scientific work.

Owen’s Enduring Influence

More than a century after his death in 1892, Richard Owen’s scientific influence continues to reverberate through multiple disciplines. His taxonomic work, particularly the creation of Dinosauria, established fundamental categories that still guide paleontological classification today. Modern museum practices worldwide reflect Owen’s vision of public institutions that seamlessly combine research and education. The field of comparative anatomy, though transformed by evolutionary theory and modern genetics, still employs analytical approaches pioneered by Owen in the nineteenth century. Perhaps most significantly, dinosaurs—the prehistoric creatures he named and first interpreted for the public—have become cultural icons that continue to inspire scientific curiosity and wonder across generations. Every child who marvels at a dinosaur skeleton or learns the names of prehistoric creatures is, in some small way, experiencing the legacy of Richard Owen’s scientific vision. Though his theories have been largely superseded, the vocabulary and categorical frameworks he established continue to shape how we understand and communicate about the natural world.

Richard Owen stands as one of scientific history’s most consequential figures, a brilliant anatomist whose linguistic invention—”dinosaur”—transformed not only paleontology but popular culture. His complex legacy encompasses groundbreaking research, institutional development, fierce scientific rivalries, and occasional ethical lapses. While some of Owen’s theories have been discarded and his opposition to Darwinian evolution places him on the wrong side of scientific history, his contributions to comparative anatomy and paleontology remain foundational. The magnificent Natural History Museum in London and the enduring fascination with dinosaurs serve as physical and cultural monuments to the man who gave these “terrible lizards” their name. Owen’s story reminds us that scientific progress often emerges through complicated human figures whose brilliance and flaws are inextricably intertwined, and whose words can echo through centuries beyond their original context.