In the annals of exploration and paleontology, few figures loom as large as Roy Chapman Andrews, whose adventurous spirit and groundbreaking discoveries have cemented his legacy as one of history’s greatest fossil hunters. Born in 1884 in Beloit, Wisconsin, Andrews would go on to lead expeditions that revolutionized our understanding of prehistoric life and evolutionary history. His daring expeditions across the Gobi Desert, complete with camel caravans, automobile convoys, and encounters with bandits, sandstorms, and poisonous snakes, have led many to consider him the real-life inspiration for the fictional character Indiana Jones. Beyond the adventure and romance, however, Andrews made profound scientific contributions that continue to shape our understanding of dinosaurs and early mammals to this day.

Early Life and Career Beginnings

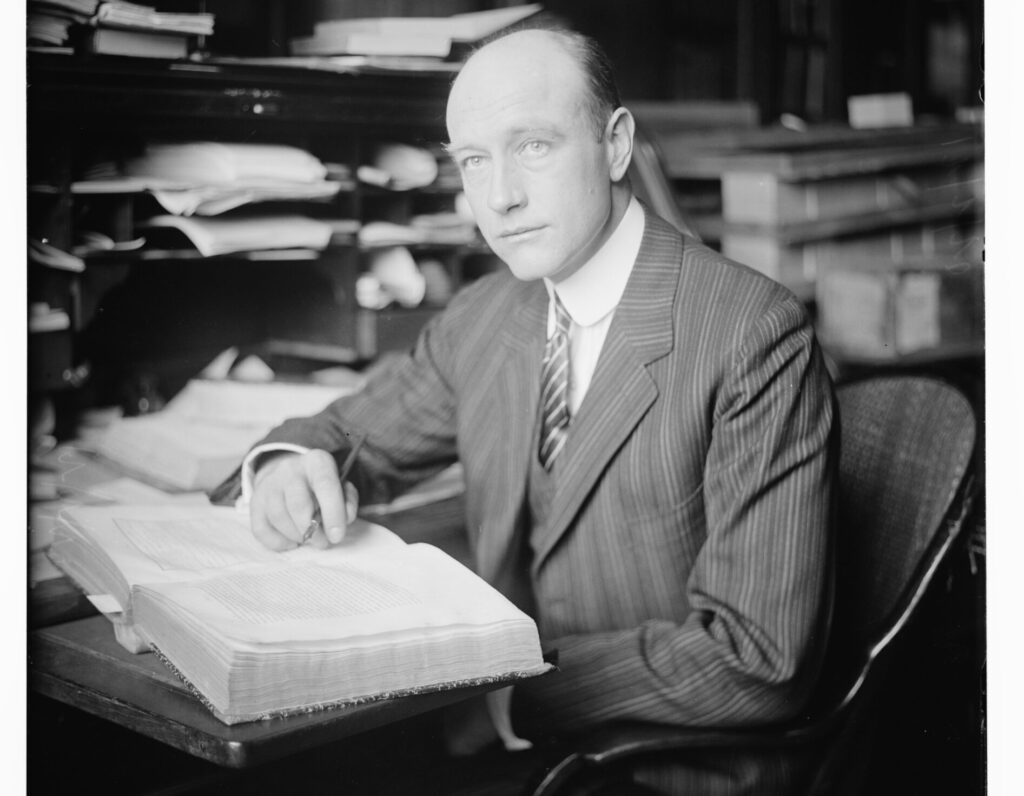

Roy Chapman Andrews was born on January 26, 1884, in Beloit, Wisconsin, where his fascination with natural history began at an early age. As a child, he spent countless hours exploring local forests and waterways, developing keen observational skills that would serve him well in his future career. After graduating from Beloit College in 1906 with a degree in English literature, Andrews set his sights on the American Museum of Natural History in New York. His determination was remarkable—when initially told there were no positions available, he famously offered to sweep the floors just to get his foot in the door. This persistence paid off, and he was hired as a taxidermist despite having no formal training. Within this prestigious institution, Andrews would gradually work his way up from a humble assistant to becoming the museum’s director, demonstrating his exceptional abilities and unwavering dedication to scientific discovery.

First Expeditions and the Call of Asia

Andrews’ career as an explorer began modestly with trips to Alaska and Vancouver Island to collect marine mammal specimens. These early expeditions showcased his natural aptitude for fieldwork and his meticulous attention to detail in specimen collection. By 1908, Andrews had set his sights on more distant horizons, embarking on his first journey to Asia with a focus on studying whales and other marine mammals along the Japanese coast. This initial foray into Asia ignited a lifelong passion for the continent and its scientific mysteries. Between 1909 and 1910, he conducted pioneering research on the Korean peninsula and in Japan, collecting valuable zoological specimens and establishing relationships with local scientists and officials that would prove crucial for his future expeditions. During this period, Andrews demonstrated not only scientific acumen but also remarkable cultural adaptability, learning languages and customs that helped him navigate foreign territories with relative ease and respect—qualities that distinguished him from many Western explorers of his era.

The Central Asiatic Expeditions: Planning a Scientific Revolution

The Central Asiatic Expeditions, which would become Andrews’ most celebrated achievement, began to take shape in the aftermath of World War I. Recognizing Mongolia’s potential as a paleontological treasure trove, Andrews meticulously planned a series of ambitious expeditions to the Gobi Desert—a region largely unexplored by Western scientists. The planning phase showcased Andrews’s exceptional organizational abilities and fundraising prowess, as he secured substantial financial backing from wealthy patrons and the American Museum of Natural History. Between 1921 and 1930, Andrews would lead five major expeditions into this harsh environment, assembling a multidisciplinary team that included geologists, paleontologists, zoologists, and photographers. His vision extended beyond fossil hunting to include comprehensive scientific documentation of the region’s geology, flora, fauna, and even anthropological studies. This holistic approach to scientific exploration was revolutionary for its time and established a template for future expeditions worldwide.

Discovering Dinosaur Eggs at Flaming Cliffs

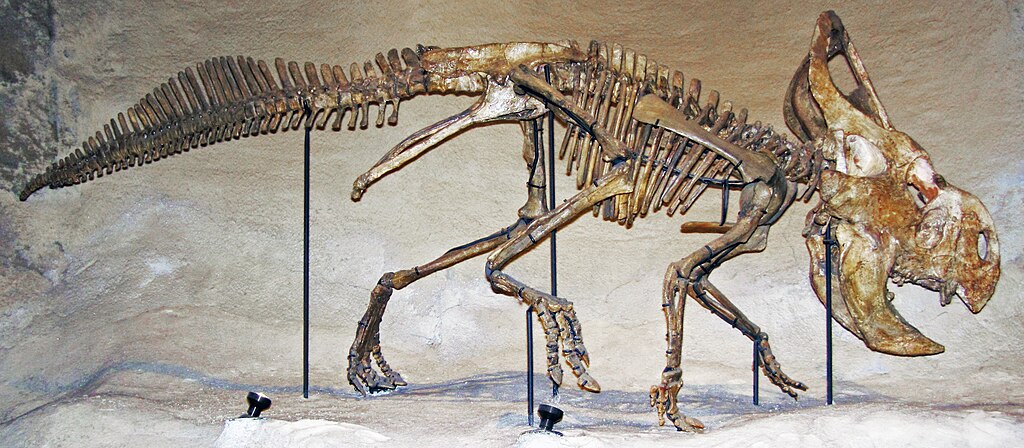

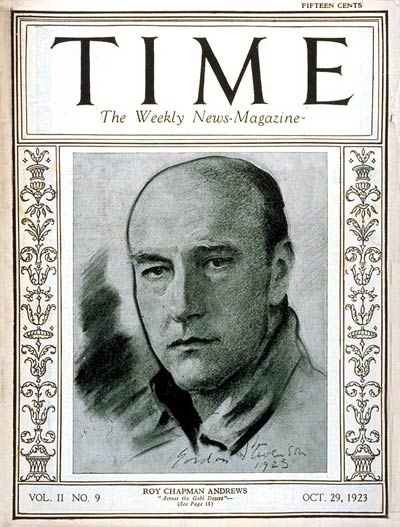

The 1923 expedition to the Gobi Desert yielded what is perhaps Andrews’ most famous discovery—the first scientifically confirmed dinosaur eggs at the site now known as the Flaming Cliffs (Bayn Dzak). This remarkable find occurred when team member George Olsen noticed what appeared to be fossil eggs eroding from the vibrant red sandstone formations. Initially skeptical, Andrews and his team soon realized they had uncovered something extraordinary—a clutch of eggs laid by a previously unknown dinosaur species they named Protoceratops. The discovery made headlines worldwide and provided the first tangible evidence of dinosaur reproductive biology, confirming that dinosaurs laid eggs rather than giving birth to live young. Additionally, the nesting sites offered unprecedented insights into dinosaur parental behavior and community structure. The finding was doubly significant as it contradicted prevailing scientific narratives about dinosaur evolution and reproductive strategies, fundamentally altering our understanding of these prehistoric creatures and establishing the Gobi Desert as a premier site for paleontological research.

Velociraptor: Unearthing the World’s Most Famous Predator

In 1924, during his second major Gobi expedition, Andrews’ team made another groundbreaking discovery—the first complete specimens of Velociraptor mongoliensis, a small but formidable carnivorous dinosaur that would later gain worldwide fame through the Jurassic Park franchise. This discovery was particularly significant because the team found a Velociraptor specimen seemingly locked in combat with a Protoceratops, providing rare evidence of predator-prey interaction in the fossil record. The “fighting dinosaurs” fossil, as it came to be known, captured a dramatic moment frozen in time approximately 80 million years ago, likely when both creatures were buried alive during a sandstorm or landslide. Andrews’ field notes describe his immediate recognition of the specimen’s scientific importance, noting its well-preserved sickle-shaped claws and agile build. This discovery fundamentally reshaped scientific understanding of dinosaur behavior and predatory adaptations, suggesting that these creatures were far more complex and dynamic than previously thought.

Innovations in Field Expedition Technology

Roy Chapman Andrews revolutionized paleontological fieldwork through his pioneering use of automotive technology in scientific expeditions. Breaking with the traditional reliance on pack animals, Andrews introduced a fleet of specially modified Dodge cars and trucks to navigate the challenging terrain of the Gobi Desert—the first motorized caravan used for such purposes. This technological innovation dramatically increased the expedition’s mobility, allowing his team to cover vast stretches of territory and transport heavier equipment and larger specimens than previously possible. Andrews carefully documented the vehicles’ performance, creating detailed maintenance protocols that would influence future expeditions worldwide. Additionally, he incorporated aerial photography for site mapping and invested in portable radio equipment to maintain communication with base camps and the outside world. These technological adaptations weren’t merely conveniences—they fundamentally transformed the practice of paleontological fieldwork, establishing new standards for expedition efficiency and scientific documentation that would influence generations of researchers to follow.

Dangerous Encounters: Bandits, Snakes, and Political Unrest

Andrews’ expeditions were fraught with dangers that rivaled any fictional adventure, cementing his reputation as a real-life action hero. Throughout his Gobi Desert explorations, his caravans faced repeated threats from armed bandits and warlord forces, situations Andrews navigated with a combination of diplomacy, firearms proficiency, and sheer nerve. In his autobiography “Under a Lucky Star,” he recounts narrowly escaping an ambush by utilizing his exceptional marksmanship—a skill he had developed since childhood and regularly practiced during expeditions. Natural hazards proved equally threatening, with the team enduring violent sandstorms that could strip paint from vehicles and cause debilitating conditions like “Gobi eye,” a painful inflammation caused by windblown sand particles. Perhaps most famously, Andrews had multiple close calls with deadly pit vipers, leading to his often-quoted remark: “I’ve always wanted to be an explorer, but I never thought I’d have to be such a good shot.” Beyond these physical dangers, Andrews’ later expeditions navigated complex geopolitical tensions as China and Mongolia experienced revolutionary upheaval, requiring delicate negotiations with changing authorities and sometimes hasty evacuations when conditions deteriorated.

Scientific Significance of the Gobi Discoveries

The scientific impact of Andrews’ Gobi Desert expeditions extended far beyond headline-grabbing dinosaur discoveries, fundamentally reshaping multiple scientific disciplines. His team’s findings challenged the prevailing “Asia Hypothesis,” which posited that Asia served as the evolutionary cradle for many major animal groups. The discovery of primitive mammals alongside dinosaur fossils provided crucial evidence for understanding mammalian evolution during the Mesozoic era, demonstrating greater diversity than previously recognized. Andrews’ expeditions also yielded groundbreaking geological insights through the work of team member Walter Granger, who developed the first comprehensive stratigraphic mapping of the Gobi region, establishing a chronological framework still used by scientists today. The multidisciplinary nature of the expeditions produced valuable botanical and zoological collections that documented previously unknown species and ecological relationships. Perhaps most significantly, the vast fossil collection—totaling over 25,000 specimens—included not just sensational dinosaur finds but also microvertebrates, insects, and plant fossils that collectively provided an unprecedented window into entire Cretaceous ecosystems.

Leadership Style and Team Management

Andrews displayed exceptional leadership abilities that maximized his expeditions’ effectiveness under extremely challenging conditions. Unlike many expedition leaders of his era who maintained rigid hierarchies, Andrews fostered a collaborative atmosphere where team members, regardless of their formal position, could contribute ideas and expertise. His journals reveal careful attention to team morale, including organizing regular recreational activities and celebration dinners after significant discoveries to maintain spirits during lengthy field seasons. Andrews demonstrated remarkable cultural sensitivity in managing relations with local Mongolian guides and workers, learning basic Mongolian phrases, and respecting indigenous knowledge about terrain and weather patterns. His meticulous planning extended to provisions and medical supplies, with detailed inventories ensuring team members’ basic needs were met despite their remote location. Perhaps most notably, Andrews maintained detailed expedition records that highlighted individual team members’ contributions rather than claiming singular credit for discoveries—a practice that earned him lasting loyalty from scientific collaborators like Walter Granger and Peter Kaisen, many of whom accompanied him on multiple expeditions throughout his career.

Andrews as Public Figure and Science Communicator

Roy Chapman Andrews excelled not only as a scientist but also as a masterful science communicator who captivated the public imagination. Following each expedition, he undertook extensive lecture tours across America and Europe, delivering engaging presentations that combined scientific findings with thrilling adventure narratives. His natural charisma and storytelling abilities made complex paleontological concepts accessible to general audiences, significantly raising public awareness and appreciation for natural history. Andrews authored numerous books that reached wide audiences, including bestsellers like “On the Trail of Ancient Man” (1926) and his autobiography “Under a Lucky Star” (1943), works that balanced scientific rigor with compelling personal anecdotes. His relationship with the media was unusually sophisticated for his time—Andrews regularly invited journalists to participate in expeditions and understood the value of dramatic photography in communicating scientific discoveries. The National Geographic Society prominently featured his adventures in their magazine, complete with striking photographs that brought distant landscapes and extinct creatures to life for millions of readers. Through these various channels, Andrews transformed paleontology from an obscure academic pursuit into an exciting frontier of discovery that captured popular imagination.

Later Career and Leadership of the American Museum

Following his groundbreaking Gobi expeditions, Andrews transitioned from field explorer to institutional leader, becoming director of the American Museum of Natural History in 1935—a position he would hold until 1942. As director, he applied his expedition management skills to institutional governance, implementing significant administrative reforms that stabilized the museum’s finances during the challenging Depression era. Andrews modernized the museum’s exhibition philosophy, championing dynamic displays that emphasized ecological relationships rather than simple taxonomic groupings—an approach that revolutionized natural history museum practices worldwide. During his directorship, he vastly expanded the museum’s educational programs, establishing lecture series and collaborations with New York public schools that dramatically increased public engagement. Despite administrative demands, Andrews continued contributing to scientific literature, publishing research based on earlier expedition findings and mentoring younger scientists who would carry forward exploration in Asia after political circumstances prevented his return. His leadership coincided with a transformative period in the museum’s history, as the institution’s focus shifted from pure collection-building toward broader educational missions and public science communication—a transition Andrews both embodied and accelerated.

Retirement and Literary Legacy

After retiring from the American Museum of Natural History in 1942, Andrews relocated to Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, where he entered a prolific phase as an author and science historian. During these later years, he produced some of his most enduring literary works, including his definitive autobiography “Under a Lucky Star” (1943), which chronicled his remarkable journey from small-town Wisconsin to international scientific fame. Andrews completed nearly a dozen books during retirement, ranging from children’s literature that introduced young readers to natural history concepts to more reflective works examining the philosophical dimensions of scientific exploration. His retirement writings reveal his evolution as a conservationist, with increasingly urgent calls for environmental protection based on his firsthand observations of habitat destruction across Asia. Despite physical limitations that prevented further fieldwork, Andrews maintained active correspondence with active explorers and paleontologists worldwide, serving as a mentor to a new generation of field scientists. His home became an informal salon for visiting naturalists, filmmakers, and writers seeking to understand the golden age of exploration that Andrews had helped define.

The Indiana Jones Connection: Separating Fact from Fiction

The parallels between Roy Chapman Andrews and the fictional character Indiana Jones have generated enduring fascination, though the precise connection remains a subject of scholarly debate. While filmmaker George Lucas and director Steven Spielberg have never explicitly confirmed Andrews as the primary inspiration for Indiana Jones, numerous compelling similarities exist. Both figures combined academic credentials with rugged field experience, operated during the same historical period, and specialized in recovering precious artifacts from remote locations. Andrews’ signature outfit—featuring a wide-brimmed hat and revolver—visually echoes the iconic Indiana Jones appearance, and both encountered political intrigue in their Asian expeditions. Additionally, both men divided their time between field exploration and prestigious academic institutions—Andrews at the American Museum of Natural History and the fictional Jones at Marshall College. However, meaningful differences exist: unlike the treasure-seeking Jones, Andrews conducted expeditions primarily for scientific purposes and worked openly with host governments rather than engaging in artifact removal. Contemporary archivists at Beloit College, which houses Andrews’ papers, suggest that while he likely influenced the character’s development, Indiana Jones represents a composite figure drawing from multiple explorers of the early 20th century.

Lasting Scientific and Cultural Impact

Roy Chapman Andrews’ contributions continue to resonate in both scientific research and popular culture nearly a century after his most famous expeditions. His Gobi Desert discoveries fundamentally altered our understanding of dinosaur evolution, with sites he identified remaining active research locations for international paleontological teams today. The extensive collections he assembled still yield new scientific insights as researchers apply advanced technologies like CT scanning and DNA analysis to specimens he recovered. In the realm of exploration methodology, his innovations in expedition planning, technology integration, and multidisciplinary teamwork established standards that influence scientific field research across disciplines. Andrews’s narrative approach to science communication pioneered techniques now considered essential for public engagement, with his books remaining in print and influencing generations of science writers. His life story continues inspiring exhibits at institutions worldwide, including permanent installations at the American Museum of Natural History and the Rockford Museum Center. Perhaps most significantly, Andrews embodied a transitional moment in scientific history—bridging the era of gentleman-explorers with modern professional science—while demonstrating that scientific rigor and public accessibility could coexist without compromising either value.

The Adventurous Life and Lasting Legacy of Roy Chapman Andrews

Roy Chapman Andrews stands as one of the most remarkable figures in the history of scientific exploration—a man whose adventures seemed lifted from fiction but whose discoveries reshaped our understanding of prehistoric life. From his humble beginnings in Wisconsin to the directorship of one of the world’s premier scientific institutions, Andrews combined scientific rigor with an adventurer’s spirit in ways that continue to inspire. His expeditions to the Gobi Desert yielded discoveries that fundamentally altered our understanding of dinosaur evolution and behavior, while his innovative approaches to expedition management and public communication transformed how science engages with both landscapes and audiences. Whether or not he directly inspired Indiana Jones, Andrews’ real-life achievements—uncovering dinosaur eggs, documenting new species, and navigating political unrest and natural dangers—surpass even the most dramatic Hollywood narratives. His legacy endures not just in museum collections and scientific papers but in how we conceptualize the very nature of exploration and the endless possibilities that await those bold enough to venture into unknown territory.