In the annals of scientific history, few moments have captured the imagination quite like the coining of the term “dinosaur.” This linguistic creation, now a household word inspiring everything from serious scientific inquiry to blockbuster films, emerged from the mind of a brilliant yet controversial Victorian anatomist named Sir Richard Owen. His scientific contribution fundamentally changed how we understand prehistoric life and established a framework for paleontology that persists to this day. The story behind the birth of the word “dinosaur” reveals not only the development of a scientific concept but also provides a window into the competitive scientific atmosphere of 19th century Britain, where natural history was undergoing a revolutionary transformation.

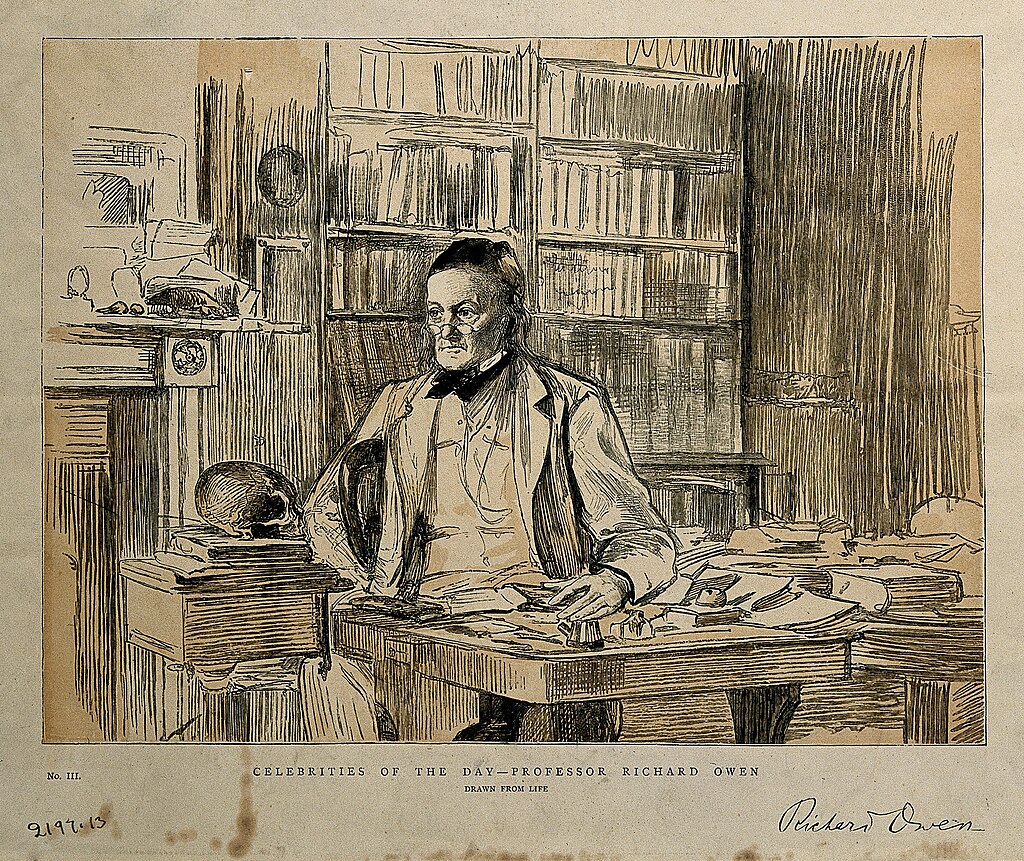

The Man Behind the Name: Richard Owen’s Early Life

Born in Lancaster, England, in 1804, Richard Owen emerged from relatively humble beginnings to become one of the most influential scientists of the Victorian era. As a young man, Owen showed an early aptitude for anatomy and medicine, eventually securing an apprenticeship with a local surgeon at the age of fourteen. This early exposure to medical practice would prove formative, developing his meticulous attention to detail and establishing his interest in comparative anatomy. After completing his medical education at the University of Edinburgh and St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, Owen became increasingly drawn to the study of comparative anatomy rather than medical practice. His exceptional skill in dissection and analysis soon attracted the attention of influential mentors, including the renowned surgeon John Abernethy, who recognized the young man’s potential and helped guide his early career. These foundational experiences laid the groundwork for Owen’s later scientific achievements, including his revolutionary work on extinct reptiles.

Owen’s Rise at the Royal College of Surgeons

Owen’s career trajectory accelerated dramatically when he secured a position at the Royal College of Surgeons in London, home to the extraordinary anatomical collection assembled by the legendary surgeon John Hunter. Appointed as the first Hunterian Professor of Comparative Anatomy and Physiology in 1836, Owen gained access to one of the world’s finest collections of anatomical specimens. This position provided him with unparalleled opportunities to examine and catalog diverse biological materials, from the mundane to the exotic. Owen’s meticulous work with the Hunterian Collection established his reputation as Britain’s premier comparative anatomist. During this period, he conducted groundbreaking research on numerous animal specimens, including the recently discovered Nautilus, various marsupials, and the mysterious great apes that were beginning to arrive from Britain’s expanding colonial territories. His growing expertise in comparative anatomy positioned him perfectly for the analytical challenges presented by the increasingly frequent discoveries of fossil remains occurring throughout Britain and Europe.

The Puzzle of Prehistoric Reptiles

By the 1830s and 1840s, Britain was experiencing what historians have called “dinosaur fever,” though the term itself had yet to be coined. Large fossilized bones and teeth were being unearthed at various sites across England, particularly in quarries and coastal exposures. These discoveries included specimens we now recognize as belonging to Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and Hylaeosaurus—the three genera that would form Owen’s original conception of Dinosauria. Early interpretations of these fossils varied wildly, with some naturalists suggesting they belonged to enormous lizards, while others proposed connections to modern crocodiles or even mammals. The scientific community lacked a cohesive framework for understanding these mysterious creatures from deep time. Owen’s rigorous anatomical approach allowed him to identify key similarities and differences between these fossil specimens and modern reptiles. His analysis revealed that these were not simply “giant lizards” as many had assumed, but represented something altogether different—a distinct group of animals that shared certain anatomical features unlike anything seen in living reptiles. This realization would lead to his momentous taxonomic innovation.

The 1841 Report: A Landmark in Paleontology

In 1841, Owen presented his landmark “Report on British Fossil Reptiles” to the British Association for the Advancement of Science. This comprehensive document represented years of meticulous study and comparison of the accumulated fossil evidence. Within this report, Owen made the fateful decision to establish a completely new taxonomic group to contain these remarkable prehistoric reptiles, which he recognized as sharing several distinct anatomical features. Most notably, Owen identified unique characteristics in their vertebral column, with sacral vertebrae fused into a structure resembling that found in mammals rather than modern reptiles. He noted their limbs were positioned directly beneath their bodies rather than splayed to the sides like those of living reptiles, suggesting these creatures were not belly-draggers but rather stood with an erect posture. For this new taxonomic group, Owen needed a name that would adequately convey the significance and distinctive nature of these animals. The term he created—”Dinosauria”—would permanently alter our understanding of prehistoric life and enter the global lexicon.

The Etymology of “Dinosaur”: Terrible Lizards

Owen constructed the term “Dinosauria” from two Greek roots: “deinos” (δεινός) meaning “terrible,” “fearfully great,” or “formidable,” and “sauros” (σαῦρος) meaning “lizard” or “reptile.” Thus, the word “dinosaur” literally translates as “terrible lizard” or “fearfully great reptile.” Owen’s choice of terminology was deliberately evocative, emphasizing both the imposing size and the reptilian nature of these extinct creatures. In his own words, he selected this name “to express the pecuniary characters of, and the awe which the contemplation of their enormous magnitude is likely to inspire.” There was a certain poetry in Owen’s nomenclature that transcended mere scientific classification. While scientifically precise in recognizing these animals as reptilian in nature, the term also captured the imagination with its suggestion of something monstrous and awe-inspiring. This combination of scientific accuracy and evocative imagery helps explain why the word “dinosaur” quickly captured both scientific and public imagination, eventually becoming one of the most recognized scientific terms in the world.

The Original Dinosaur Trio

Owen’s initial conception of Dinosauria included just three genera, each representing distinct forms that had been discovered in southern England during the early nineteenth century. Megalosaurus, first described by William Buckland in 1824, was a large carnivorous dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic period whose partial remains had been found in Oxfordshire. Iguanodon, discovered by Gideon Mantell and his wife Mary Ann in Sussex, was a large herbivore known primarily from its distinctive teeth which resembled those of modern iguanas, albeit much larger. The third member of Owen’s original dinosaurian triumvirate was Hylaeosaurus, another herbivore discovered by Mantell in 1833 in Tilgate Forest, notable for its armored plates. Despite having only fragmentary remains of these three animals, Owen recognized they shared certain anatomical features that set them apart from other reptiles, both living and extinct. His insight in grouping these seemingly disparate creatures into a single taxonomic category represents one of the most important conceptual leaps in the history of paleontology, establishing a framework that would accommodate the thousands of dinosaur species subsequently discovered over the next two centuries.

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs: Bringing Prehistory to Life

Owen’s scientific ideas about dinosaurs reached their most public expression through his collaboration with sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins on the Crystal Palace dinosaur models. Following the success of the Great Exhibition of 1851, the Crystal Palace was relocated to Sydenham in South London, where an educational park was created featuring life-sized models of prehistoric creatures. Owen served as the scientific consultant for this groundbreaking project, advising Hawkins on how these ancient animals might have appeared in life. The resulting sculptures, completed in 1854, became the world’s first full-scale dinosaur reconstructions and offered Victorian audiences their first glimpse of these “terrible lizards.” Though wildly inaccurate by modern standards—the Iguanodon was depicted as a heavy, quadrupedal beast resembling a rhinoceros with a horn on its nose (actually its thumb spike)—these models represented the best scientific understanding of the time. The Crystal Palace dinosaurs became immensely popular attractions, bringing Owen’s concept of Dinosauria to the general public and helping to spark the dinosaur mania that continues to this day. These historic models still stand in Crystal Palace Park, protected as Grade I listed monuments that document an important chapter in the history of scientific understanding.

Owen’s Rivalries and Controversies

Despite his brilliance, Owen’s career was marked by bitter scientific rivalries and ethical controversies that complicated his legacy. His most notorious feud was with Gideon Mantell, the discoverer of Iguanodon. Owen consistently undermined Mantell’s contributions, at times taking credit for Mantell’s insights or dismissing his work, behavior that continued even after Mantell’s death in 1852. Similarly contentious was Owen’s relationship with Charles Darwin and his supporters following the publication of “On the Origin of Species” in 1859. Though initially friendly with Darwin, Owen became one of the most prominent scientific critics of evolutionary theory, preferring his own more conservative concept of “archetypes” that preserved a role for divine creation. Owen was also notorious for his ruthless tactics in scientific disputes, including anonymous self-promotion in review articles and the deliberate miscrediting of rivals’ discoveries. These personal controversies have somewhat overshadowed Owen’s genuine scientific contributions, including his dinosaur work, and have contributed to his relatively diminished historical reputation compared to contemporaries like Darwin. Modern historians recognize both Owen’s undeniable brilliance and his problematic personal and professional conduct, presenting a more nuanced view of this complex scientific figure.

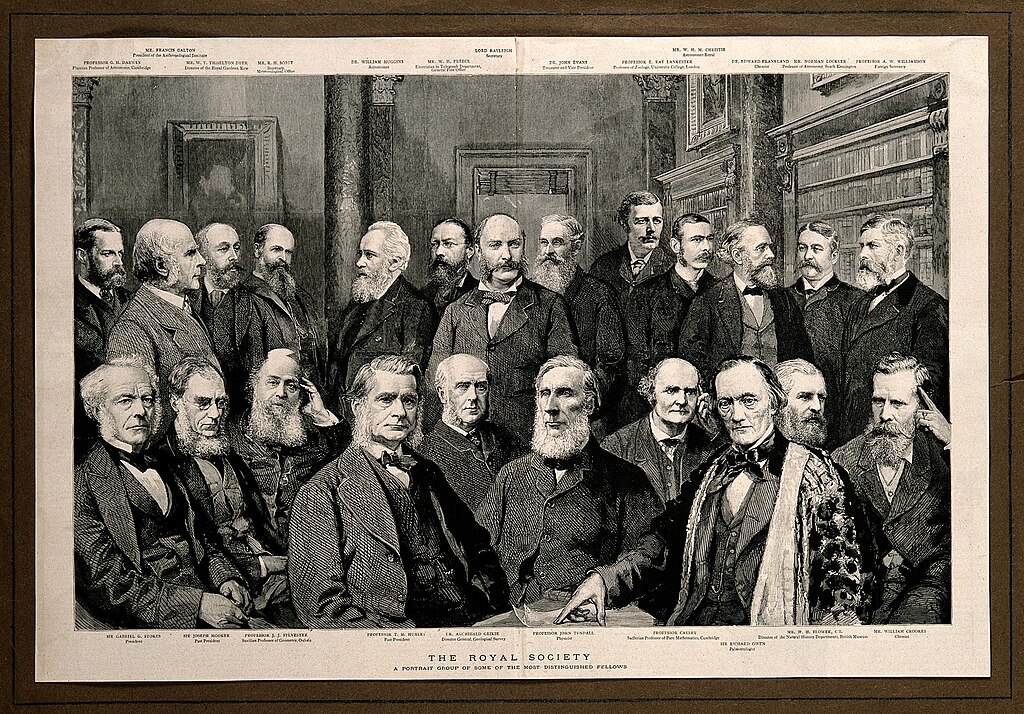

The Natural History Museum and Owen’s Later Career

Perhaps Owen’s most enduring institutional legacy was his pivotal role in founding London’s Natural History Museum. For decades, Owen advocated tirelessly for a dedicated natural history museum separate from the British Museum, arguing that the nation’s growing natural history collections deserved their own showcase. His persistence finally paid off when the magnificent Romanesque building in South Kensington opened in 1881, with Owen serving as its first director. This achievement represented the culmination of Owen’s career and his vision for public education in natural science. In his later years, Owen continued his research while overseeing the development of the new museum, though his scientific influence gradually diminished as evolutionary theory—which he had resisted—became the dominant paradigm in biology. After a long and remarkably productive career spanning nearly sixty years, Owen retired in 1883 and was awarded a knighthood for his contributions to science. Despite the controversies that surrounded him, Owen’s institutional vision transformed how natural history was presented to the public, creating a model that influenced museums worldwide. When he died in 1892, aged 88, the museum he had fought to create stood as a physical embodiment of his impact on Victorian science.

How Owen’s Dinosaur Concept Has Evolved

The scientific understanding of what constitutes a dinosaur has changed dramatically since Owen’s initial classification, reflecting over 180 years of subsequent fossil discoveries and interpretational advances. Owen conceived of dinosaurs as advanced reptiles, distinguished from their contemporaries by their upright posture and mammal-like anatomical features. However, he had no conception of their diversity, their evolutionary relationships to birds, or their varied physiological adaptations. Modern paleontologists recognize Dinosauria as a much more precisely defined clade (a complete evolutionary grouping) including all descendants of the most recent common ancestor of Triceratops and modern birds. This modern definition, formalized through phylogenetic systematics in the late 20th century, represents a significant departure from Owen’s more limited taxonomic concept. Perhaps most significantly, we now understand that dinosaurs never entirely went extinct—birds are literally living dinosaurs, specifically evolved from small, feathered theropod dinosaurs of the Jurassic period. This evolutionary connection between dinosaurs and birds, first proposed by Thomas Henry Huxley in the 1860s but only widely accepted a century later, would have been utterly foreign to Owen, who rejected evolutionary theory altogether. Despite these conceptual transformations, Owen deserves credit for recognizing these animals as a distinct and unique group requiring their own taxonomic category.

The Cultural Impact of the Word “Dinosaur”

Few scientific terms have permeated global culture as thoroughly as “dinosaur,” transcending its taxonomic origins to become a versatile metaphor and an enduring source of fascination. Within decades of Owen’s coining of the term, dinosaurs began appearing in popular literature, most notably in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1912 novel “The Lost World,” which established the persistent trope of dinosaurs surviving in remote regions. The cultural presence of dinosaurs exploded in the twentieth century with films like the 1933 “King Kong,” featuring stop-motion dinosaurs created by Willis O’Brien, and later reached unprecedented heights with Steven Spielberg’s “Jurassic Park” in 1993, which revolutionized how dinosaurs were portrayed in popular media. Beyond entertainment, “dinosaur” has entered common parlance as a metaphor for obsolescence or resistance to change, as when outdated institutions or technologies are labeled “corporate dinosaurs.” Conversely, dinosaurs have become powerful educational tools, serving as “gateway organisms” that introduce children to concepts in biology, evolution, and geological time. This remarkable cultural penetration speaks to the evocative power of Owen’s original terminology, which continues to spark imagination nearly two centuries after its creation.

Richard Owen’s Contested Legacy

Owen’s scientific legacy remains decidedly mixed, reflecting both his undeniable contributions and his controversial personal conduct. As the originator of the concept and term “dinosaur,” Owen deserves recognition for establishing a taxonomic framework that has proven remarkably durable despite nearly two centuries of subsequent discoveries and theoretical revisions. His comparative anatomical work was genuinely groundbreaking, and his institutional vision transformed natural history education through the founding of London’s Natural History Museum. Yet these achievements must be balanced against Owen’s less admirable qualities, including his habit of undermining colleagues, appropriating others’ discoveries, and engaging in vicious priority disputes. His steadfast opposition to Darwinian evolution placed him on the wrong side of biology’s most important theoretical advance, diminishing his scientific reputation in the decades following his death. In recent years, historians of science have worked to provide a more nuanced assessment of Owen’s life and work, acknowledging both his brilliance and his flaws. Some scholarly reassessment has attempted to rehabilitate aspects of Owen’s theoretical positions, suggesting they were more sophisticated than previously recognized. Nevertheless, Owen remains a paradoxical figure: the man who gave us “dinosaur” but whose personal conduct often fell short of scientific ideals.

The Enduring Significance of Owen’s Terminology

Almost two centuries after Owen introduced the term “Dinosauria” to the British Association for the Advancement of Science, his linguistic creation continues to serve as a fundamental concept in paleontology and a cultural touchstone worldwide. The word itself has proven remarkably versatile, spawning derivatives like “dinosaurian,” “dinosauromorph,” and even the playful “dinophilia” to describe enthusiastic interest in these ancient reptiles. Owen could hardly have imagined that his taxonomic designation would eventually encompass thousands of species spanning approximately 165 million years of Earth’s history, from the modest Nyasasaurus of the Middle Triassic to the diverse avian dinosaurs still flourishing today. The longevity of Owen’s terminology speaks to his insight in recognizing these animals constituted a distinct and significant group that demanded its own classification. While virtually every aspect of our understanding of dinosaurs has evolved dramatically since 1841, the fundamental concept Owen identified—that these animals represented something unique in the history of life—has been repeatedly validated by subsequent research. In this sense, the term “dinosaur” represents Owen’s most enduring scientific legacy, continuing to facilitate both scientific communication and public engagement with paleontology long after most of his other theories have been superseded or abandoned.

Conclusion: The Lasting Impact of a Single Word

The story of Richard Owen and his creation of the word “dinosaur” reveals how scientific terminology can transcend its original technical context to become a powerful cultural force. Owen’s term emerged from the competitive intellectual environment of Victorian science, combining rigorous anatomical observation with a poet’s sense for evocative language. Though Owen himself was a complex and often controversial figure whose theoretical framework has largely been superseded, his linguistic innovation continues to structure both scientific understanding and public imagination. The concept he recognized—that the fossils of Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and Hylaeosaurus belonged to a distinct and remarkable group of animals—has proven extraordinarily fertile ground for subsequent scientific investigation. Perhaps most significantly, the word “dinosaur” has helped humanity conceptualize deep time and our planet’s remarkable evolutionary history, making tangible the otherwise almost incomprehensible reality that Earth was dominated by reptilian megafauna for far longer than mammals