In the days before digital photography, instant communication, and peer-reviewed journals, early paleontologists relied on remarkably personal methods to share their groundbreaking discoveries. From meticulously hand-drawn sketches sent through unreliable postal systems to passionate letters debating the nature of extinct creatures, these scientists built the foundation of modern paleontology through persistence and ingenuity. Their correspondence wasn’t just scientific—it was deeply human, filled with excitement, rivalry, misunderstandings, and occasional spectacular errors that changed our understanding of prehistoric life. This article explores how these pioneering researchers, working with limited tools and knowledge, managed to collaborate across continents to piece together Earth’s ancient past.

The Dawn of Paleontological Communication

Long before standardized scientific journals and international conferences became the norm, early paleontologists relied primarily on personal correspondence to share their findings. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, this meant handwritten letters that could take months to reach their destination, if they arrived at all. These letters weren’t merely formal announcements of discoveries but often contained intimate details about the finder’s excitement, theories, and questions. Georges Cuvier, often considered the father of paleontology, maintained extensive correspondence networks throughout Europe, exchanging hundreds of letters with fellow naturalists. These early communications formed the first informal peer review system, where discoveries were debated, questioned, and gradually accepted or rejected through ongoing dialogue rather than formal publication. The personalities of these pioneers often shaped the field as much as their scientific methods did, with their personal perspectives coloring how fossils were interpreted and classified.

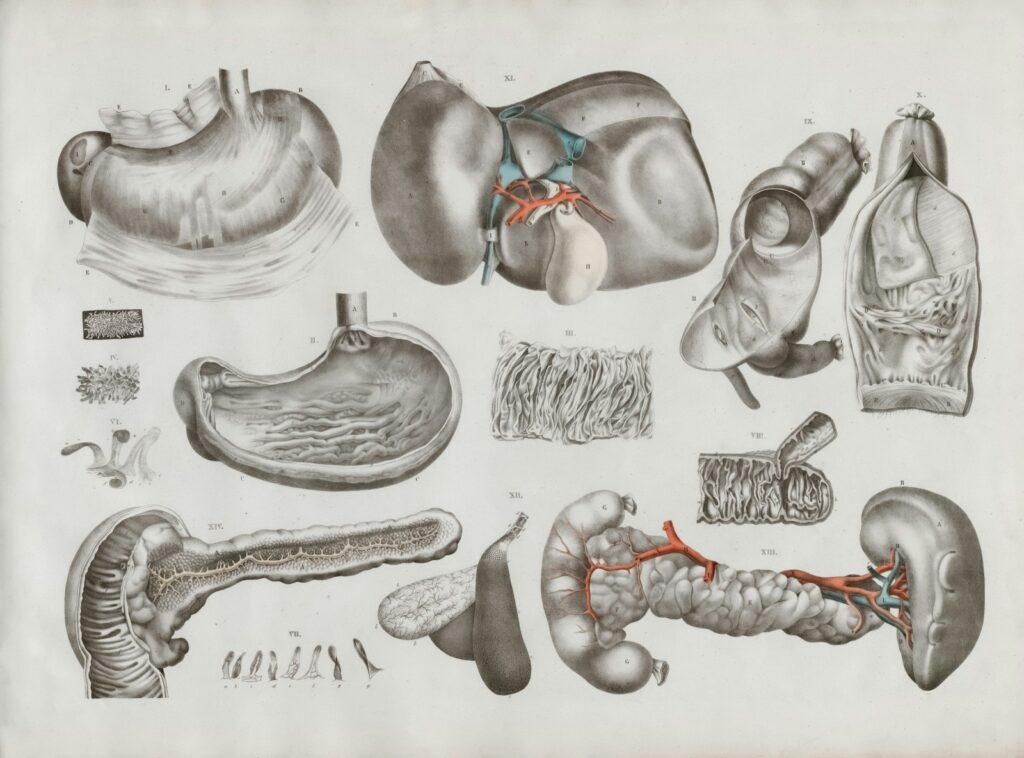

The Art of Scientific Illustration

With photography still decades away from invention, early paleontologists relied heavily on their artistic skills—or those of hired illustrators—to document their discoveries. These illustrations weren’t mere supplements to text; they were the primary means of conveying the exact appearance and details of fossils. Mary Anning, the renowned fossil collector from Lyme Regis, England, created detailed sketches of her ichthyosaur and plesiosaur findings that were essential for scientists to understand these creatures’ anatomical structures. The quality of these illustrations could make or break a scientist’s credibility, as poor renderings led to misinterpretations and scholarly disputes. Some paleontologists developed sophisticated techniques like using camera lucida devices to project fossil outlines onto paper, ensuring greater accuracy. The best illustrators combined scientific precision with artistic sensibility, creating images that were both technically accurate and aesthetically compelling enough to capture the imagination of other researchers and the public alike.

The “Bone Wars” Correspondence

Perhaps no paleontological rivalry illustrates the power of written communication better than the infamous “Bone Wars” between Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope in the late 19th century. These American paleontologists engaged in a decades-long feud that played out not only in competitive fossil hunting but in their voluminous correspondence with other scientists, museum curators, and newspaper editors. Their letters reveal not just scientific disagreements but deeply personal animosity as they each tried to discredit the other’s findings. Marsh would often write to Cope’s financial backers, subtly questioning his scientific methods, while Cope penned scathing critiques of Marsh’s fossil interpretations to journal editors. Despite their bitter rivalry, their combined correspondence network spread knowledge of North American dinosaur discoveries throughout the scientific world. Ironically, their attempts to outdo each other through letters and publications led to a massive acceleration in paleontological knowledge, even as their personal relationship deteriorated beyond repair.

Postal Systems as Scientific Infrastructure

The development of reliable international postal services in the 19th century revolutionized paleontological communication, transforming what had been an isolated pursuit into a truly global scientific endeavor. The British postal reforms of 1840, which introduced the penny post, made regular correspondence financially feasible for scientists who previously had to limit their letters due to prohibitive costs. Similarly, the establishment of international postal agreements in the 1870s created pathways for fossil sketches and descriptions to travel between continents with unprecedented reliability. Paleontologists began timing their field expeditions around mail schedules, knowing precisely when they could send updates or receive responses from colleagues. Some researchers developed complex coding systems in their letters to protect their discoveries from competing scientists who might intercept their mail. The postal system became so integral to paleontological work that expedition leaders would sometimes travel days from remote dig sites simply to reach a post office, ensuring their latest findings could be shared with the wider scientific community without delay.

Spectacular Mistakes in Fossil Reconstruction

The limitations of sketch-based communication led to some remarkable errors in early paleontology that persisted for decades. The most famous example may be the Iguanodon’s thumb spike, which Richard Owen initially placed on the creature’s nose like a rhinoceros horn based on incomplete specimens and misleading illustrations. When more complete fossils were discovered years later, the error became apparent, requiring a complete rethinking of the dinosaur’s appearance and behavior. Similarly, early reconstructions of the Brontosaurus (now Apatosaurus) famously featured the wrong skull—a Camarasaurus head placed on an Apatosaurus body—an error propagated through scientific illustrations for over a century. These mistakes weren’t merely amusing footnotes but represented genuine scientific puzzles that researchers worked collaboratively to solve through increasingly detailed correspondence. Letters debating these reconstruction errors often contained passionate arguments about anatomy, evolutionary relationships, and animal behavior, driving the field forward through controversy and correction.

Language Barriers and Translation Challenges

International paleontological communication faced significant challenges from language differences, as important discoveries made in one country often remained unknown to scientists who couldn’t read that language. German paleontologists produced extensive research on European fossils in the 19th century, but their findings spread slowly to English-speaking countries due to translation delays. Russian paleontological discoveries in the early 20th century similarly remained isolated until translators intervened. Some scientists developed interesting workarounds, such as drawing more detailed illustrations with minimal text to overcome language barriers. Others learned multiple languages specifically to access fossil research, with many leading paleontologists of the era being fluent in three or more scientific languages. Occasional mistranslations led to scientific confusion, such as when the German term “Raubdinosaurier” (predatory dinosaur) was occasionally mistranslated as “robbery dinosaur” in early English texts, causing confusion about the animal’s behavior.

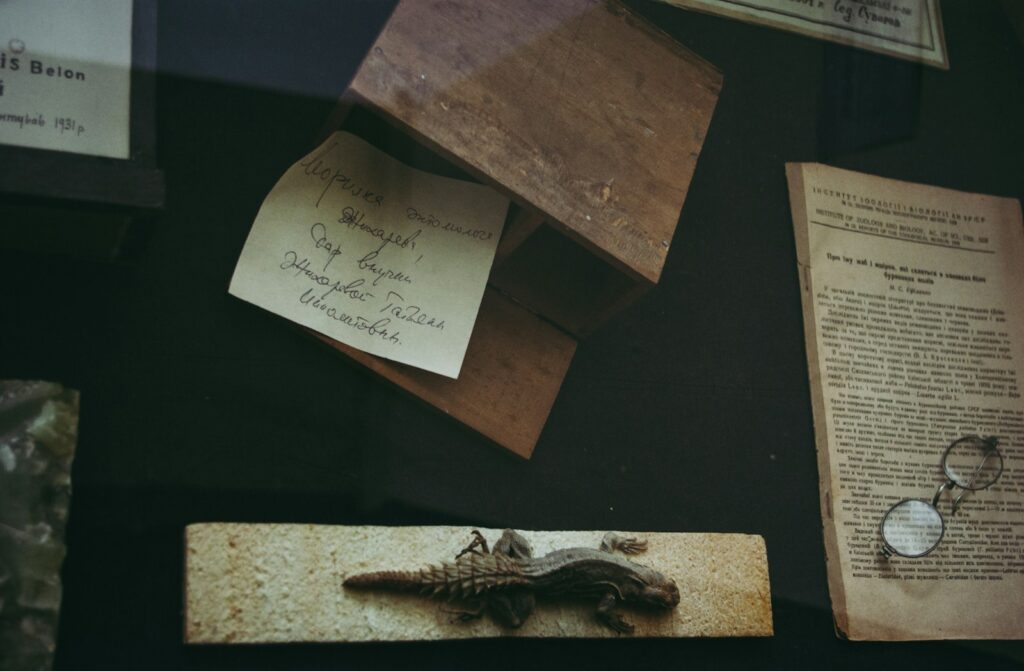

Private Collectors and Their Correspondence Networks

Not all early paleontological communication happened between professional scientists; private fossil collectors played a crucial role in information exchange. Wealthy amateur collectors like Thomas Hawkins in England maintained extensive letter networks with both professional scientists and other collectors, creating informal knowledge-sharing communities. Theseoften had the financial resources to publish lavishly illustrated private folios of their collections, which they distributed to scientific contacts. Their correspondence reveals fascinating social dynamics, as professional scientists sometimes had to carefully flatter wealthy collectors to maintain access to important specimens. Women collectors, though often excluded from formal scientific institutions, developed particularly strong correspondence networks, with figures like the Philpot sisters of Lyme Regis exchanging hundreds of letters about fossil-hunting techniques and specimen identification. These private networks sometimes preserved information about discoveries that would otherwise have been lost, as collectors documented finds that academic scientists overlooked or dismissed.

The Role of Scientific Societies and Their Publications

As paleontology matured in the 19th century, scientific societies emerged as crucial hubs for coordinating communication beyond individual correspondence. Organizations like the Geological Society of London (founded 1807) created formal channels for fossil discoveries to be presented, discussed, and published. These societies established the first peer-reviewed paleontological journals, which standardized how fossil information was shared and documented. The proceedings of these society meetings reveal how verbal presentations complemented written communications, with members asking questions and debating interpretations in real-time. Society correspondence secretaries became influential gatekeepers, determining which fossil discoveries deserved wider attention and which remained in obscurity. Membership in these societies conferred legitimacy on paleontologists and their findings, though the exclusion of women and researchers from lower social classes from many of these organizations created significant knowledge gaps. The archival records of these societies preserve not just the formal publications but the messy, creative process of scientific debate through which paleontological consensus was gradually established.

Fossil Diagrams as Universal Language

As paleontologists struggled with language barriers and terminology differences, standardized fossil diagrams emerged as a kind of universal scientific language. By the mid-19th century, conventions developed for illustrating fossils with consistent orientation, scale markers, and annotation styles that could be understood regardless of the accompanying text language. These diagrams used cross-hatching techniques to indicate depth and texture in an era before photography could capture such details. Particularly important was the development of standardized anatomical orientation terms and directional indicators in diagrams, allowing scientists to precisely describe which part of a fossil they were discussing. Museum curators created detailed cataloging illustrations that were shared between institutions, helping researchers understand collections they couldn’t visit in person. Some paleontologists became known for their distinctive illustration styles, with certain shading techniques or perspective approaches serving almost as a scientific signature that identified their work to colleagues around the world.

Public Lectures and the Popularization of Discoveries

Beyond the scientific community, early paleontologists communicated their discoveries to the public through dramatic lectures that combined scientific information with theatrical presentation. Richard Owen’s public presentations on dinosaurs in Victorian England drew massive crowds and generated extensive newspaper coverage, spreading dinosaur fever throughout society. These lectures typically featured large-scale illustrations or models that brought extinct creatures to life for audiences. The correspondence between scientists often discussed strategies for effective public communication, recognizing that public interest drove funding and institutional support for their work. Newspaper reports of these lectures, though often sensationalized, helped spread paleontological discoveries to remote areas where scientific journals never reached. Paleontologists carefully cultivated relationships with journalists through letters and interviews, understanding that public fascination with “antediluvian monsters” created the cultural support necessary for their continued research.

The Exchange of Plaster Casts and Models

When sketches and descriptions proved insufficient, early paleontologists developed sophisticated systems for sharing three-dimensional representations of fossils. By the 1830s, the practice of creating plaster casts of important specimens became widespread, allowing exact copies to be shipped to colleagues worldwide. These casts were often accompanied by detailed letters explaining specific features to examine and questions to consider. Museum administrators established formal cast exchange programs, where institutions would trade copies of their most significant fossils to build comparative collections. The correspondence surrounding these exchanges reveals complex negotiations about which specimens warranted copying and who deserved to receive them. The creation of these casts required significant artistic and technical skill, with specialists like Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins becoming famous for their ability to create scientifically accurate reproductions. For particularly important discoveries, miniature models might be included in letters themselves, tiny sculptural representations that could be held and examined by the recipient to better understand three-dimensional structures that defied simple illustration.

The Transition to Photography and Modern Communication

The introduction of photography in the mid-19th century gradually transformed paleontological communication, though the transition happened more slowly than might be expected. Early fossil photographs suffered from technical limitations, often lacking the clarity and detail of skilled illustrations, which remained preferred for scientific publication well into the 20th century. Letters from this transitional period show scientists debating the merits of different documentation methods, with many expressing skepticism about the scientific value of photographs. By the 1880s, improvements in photographic technology made it possible to capture fine fossil details, and researchers began including photographic prints with their correspondence. The development of international telegraphy allowed urgent paleontological news to travel instantly, dramatically accelerating the pace of collaborative research. Perhaps most significantly, the standardization of scientific conferences and international journals created more formal channels for discovery sharing, gradually replacing the personalized letter networks that had characterized earlier eras.

Legacy and Modern Paleontological Communication

Today’s digital paleontology, with its instant global sharing of 3D scans and CT data, evolved directly from these early communication methods. Modern paleontologists still study the correspondence of their predecessors, finding valuable scientific information in letters that were never formally published. Archives of these historical communications have become research resources in themselves, offering insights into discoveries that were forgotten or misinterpreted. The personal nature of early paleontological correspondence created a scientific culture that valued narrative and contextual understanding, aspects that remain important in contemporary paleontology despite technological changes. Digital reconstructions of fossils now travel instantly across continents, yet they serve the same fundamental purpose as those carefully inked sketches sent by stagecoach two centuries ago. The history of paleontological communication reminds us that science has always been a human conversation—sometimes flawed, often passionate, and constantly evolving as we collectively work to understand the ancient world beneath our feet.

The story of early paleontological communication is ultimately about human ingenuity overcoming immense practical challenges. These scientists, separated by oceans and limited by the technologies of their time, created networks of knowledge that transcended boundaries. Through their letters, sketches, and occasional magnificent mistakes, they didn’t just discover extinct creatures—they discovered how to collaborate across distance and time. Their communication methods may seem quaint by today’s standards, but they established the collaborative foundation upon which modern paleontology stands. As we continue to unearth new fossils and revise our understanding of prehistoric life, we build upon a tradition of shared discovery that began with those first careful sketches and enthusiastic letters, carried by horseback to colleagues who shared the same burning curiosity about Earth’s ancient past.