Within the heart of Baden-Württemberg, Stuttgart’s Natural History Museum (Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart) houses one of Europe’s most remarkable collections of Jurassic fossils, telling a fascinating story of prehistoric life that once flourished in what is now southern Germany. This treasure trove of paleontological wonders offers visitors a unique glimpse into an ancient world where bizarre marine creatures swam in tropical seas and early dinosaurs roamed lush landscapes. The museum’s extraordinary specimens, many discovered in the region’s limestone quarries, have revolutionized our understanding of Jurassic ecosystems and evolution.

The Geological Time Capsule of Southern Germany

Southern Germany represents one of the world’s most significant windows into the Jurassic period, approximately 201-145 million years ago. The region’s unique geological history created perfect conditions for exceptional fossil preservation, particularly in the limestone deposits of the Swabian Alb. During the Jurassic, much of what is now Germany was covered by a warm, shallow sea teeming with life. As creatures died, they sank to the oxygen-poor seafloor where they were rapidly buried in fine sediment, preventing decomposition. The region’s alkaline, fine-grained limestone, particularly from quarries near Holzmaden and Solnhofen, preserved even the softest tissues of ancient organisms, including skin, internal organs, and delicate structures that would normally disappear during fossilization. This rare preservation quality has made southern Germany’s fossil beds internationally famous among paleontologists and natural history enthusiasts alike.

The Museum’s Storied History

Stuttgart’s Natural History Museum boasts a rich heritage dating back to the 1791 “Cabinet of Natural Curiosities” established by Duke Carl Eugen of Württemberg. The institution gradually evolved from a royal collection into a modern scientific research center and public museum. By the mid-19th century, as fossil discoveries in Württemberg multiplied, the museum became increasingly focused on paleontology. World Wars I and II posed significant challenges, with bombing during WWII destroying parts of the collection and the museum building. Remarkably, many of the most precious specimens survived, having been evacuated to safer locations. Today’s museum, housed in both the Löwentor Museum (focusing on paleontology) and Schloss Rosenstein (featuring modern biodiversity), continues this centuries-old tradition of preserving and interpreting natural history for both scientific research and public education.

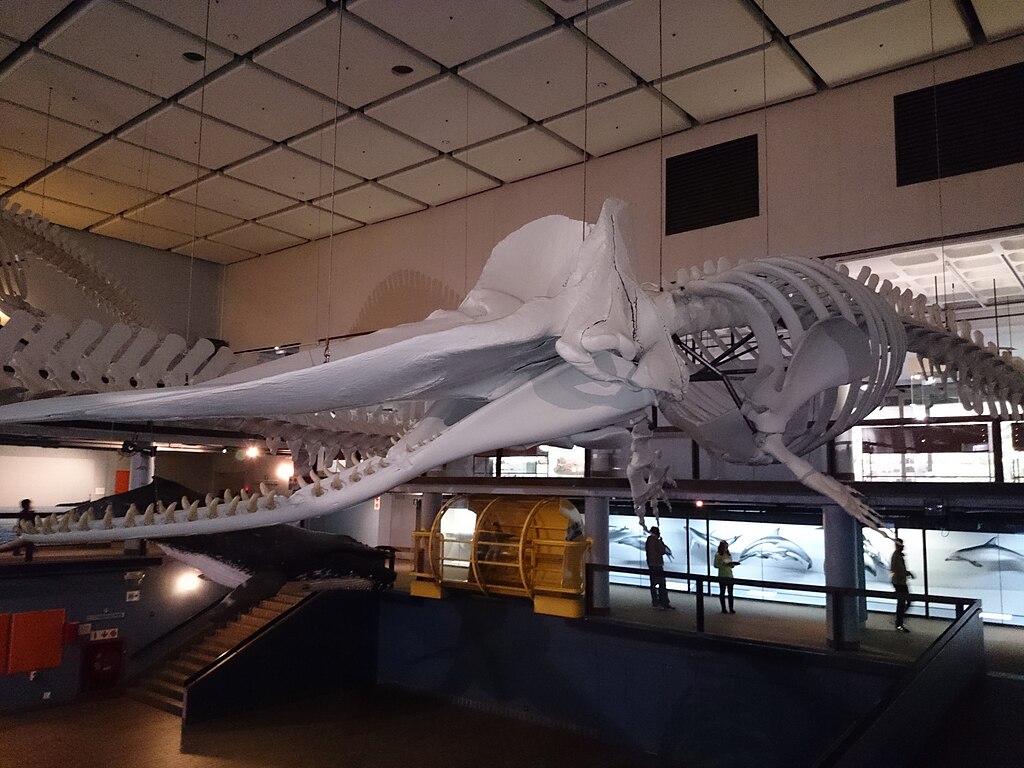

Star Attraction: The Hauff Collection

The Hauff Collection forms the cornerstone of the museum’s Jurassic exhibits and represents one of the most significant assemblages of marine reptile fossils in the world. Bernhard Hauff Sr. (1866-1950) and his son revolutionized fossil preparation techniques in the early 20th century, developing methods to reveal extraordinarily detailed specimens from the black shales of Holzmaden. Their preparation work exposed not just skeletons but also soft-tissue outlines, stomach contents, and even preserved skin impressions. The family’s quarrying operations and preparation studio produced hundreds of museum-quality specimens, with the finest examples finding their home in Stuttgart. Visitors to the museum can marvel at complete ichthyosaurs showing preserved body outlines, perfectly articulated plesiosaurs, and massive marine crocodilians, all presented with the artistic flair and scientific precision that made the Hauff workshop legendary among paleontologists worldwide.

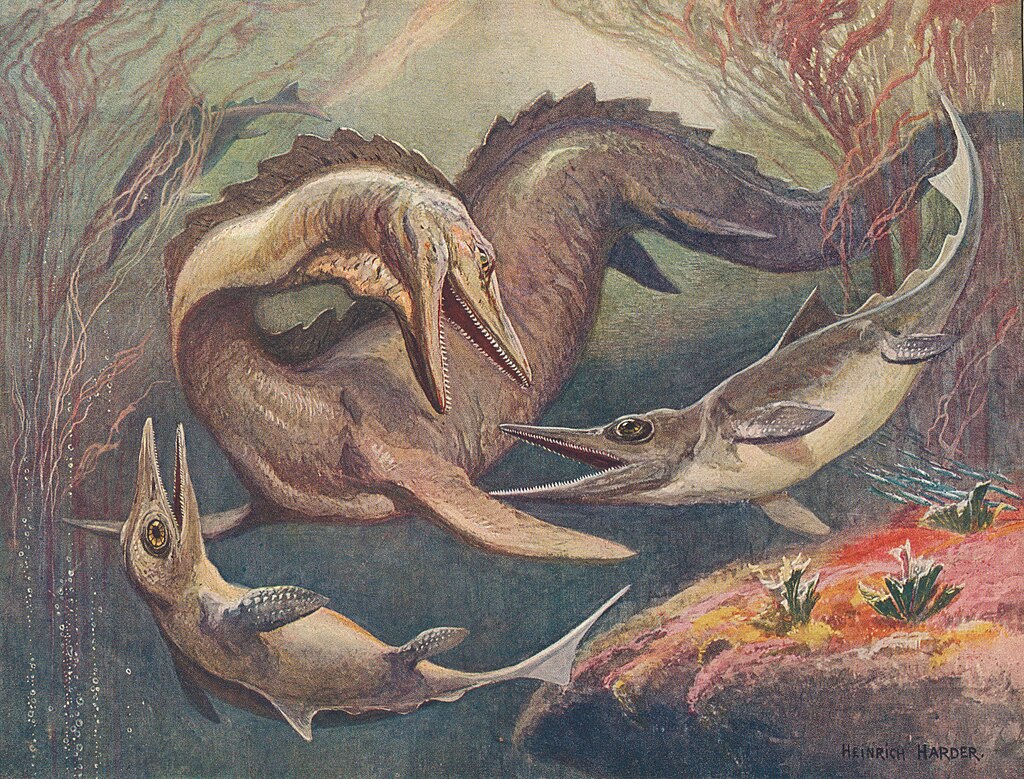

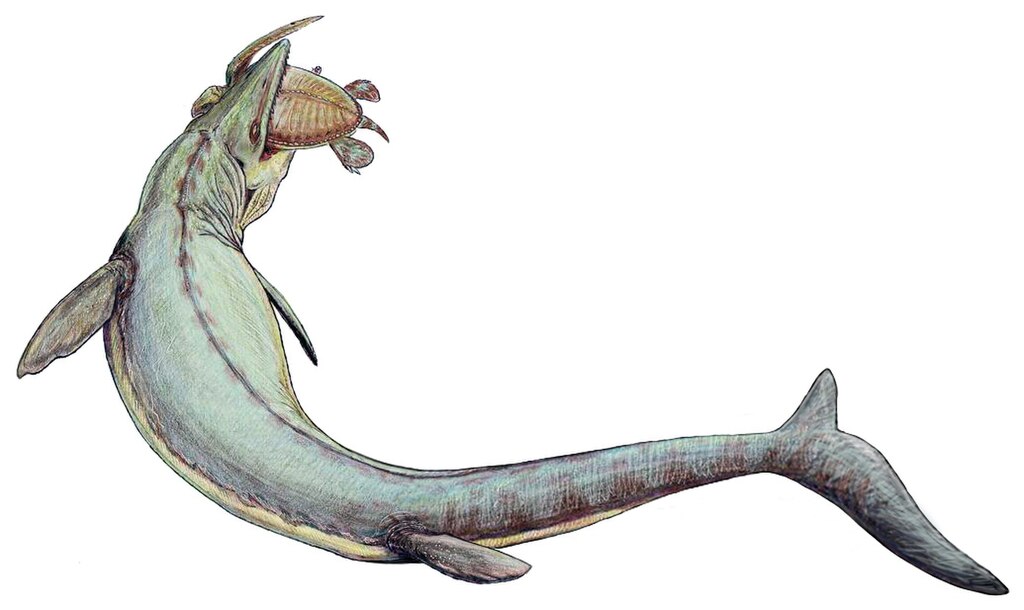

Ichthyosaurs: The Sea Dragons of Holzmaden

Ichthyosaurs represent some of the museum’s most spectacular fossils, with specimens from Holzmaden showcasing these marine reptiles in unprecedented detail. These dolphin-like creatures, whose name means “fish lizards,” evolved from land reptiles that returned to the sea, developing streamlined bodies remarkably similar to modern dolphins and tuna through convergent evolution. The museum’s collection includes examples of Stenopterygius, some preserved with outlines of their body shape, skin impressions, and even embryos visible within the body cavity of pregnant females. Perhaps most famous is a specimen showing an ichthyosaur that died during childbirth, with a baby partially emerged from the mother’s body—a poignant moment frozen in time for 182 million years. These fossils have been crucial for understanding ichthyosaur biology, revealing details about their reproductive strategies, diet, and swimming capabilities that would be impossible to determine from skeletal material alone.

Plateosaurus: Germany’s Dinosaur Icon

Towering at the entrance to the Löwentor Museum stands Plateosaurus, the most common dinosaur found in German soil and a signature specimen of the Stuttgart collection. This early sauropodomorph dinosaur lived during the Late Triassic period, approximately 214-204 million years ago, representing one of the earliest large herbivorous dinosaurs in the evolutionary timeline. The museum houses material from the famous “dinosaur graveyard” at Trossingen, where dozens of Plateosaurus individuals were discovered in what appears to have been a mass death event, possibly when the animals became trapped in mud. A full skeletal mount demonstrates how this 6-10 meter long dinosaur would have moved both quadrupedally and bipedally, while detailed exhibits explain how these animals represented an important evolutionary step toward the gigantic sauropods that would later dominate Earth’s landscapes. Interactive displays allow visitors to explore Plateosaurus anatomy, showing how its unique hand structure and teeth were adapted for its plant-eating lifestyle.

The Marine Ecosystem of the Posidonia Shale

The Posidonia Shale, dating to the Early Jurassic (approximately 182 million years ago), represents one of the most perfectly preserved ancient ecosystems on Earth, magnificently displayed in the museum’s galleries. This fossil lagerstätte (an exceptional fossil deposit) provides a comprehensive snapshot of a complete marine food web, from microscopic plankton to apex predators. Visitors can observe delicate ammonites with preserved shell chambers, squid-like belemnites with intact ink sacs, and countless fish species showing scales, fins, and even stomach contents. Large wall displays recreate the ancient seascape, showing how creatures interacted in this tropical Jurassic sea. The extraordinary preservation quality of these fossils results from a perfect combination of factors: rapid burial, oxygen-poor bottom waters that prevented decomposition, and fine-grained sediment that captured even the most delicate structures. Together, these specimens tell a story of a rich ecosystem that flourished briefly before being affected by an oceanic anoxic event that changed environmental conditions across the ancient world.

Flying Reptiles: The Pterosaurs of Germany

The museum’s pterosaur collection showcases these fascinating flying reptiles that ruled the skies during the Mesozoic era, with specimens from southern Germany being among the best preserved in the world. Unlike the marine reptiles from Holzmaden, most of the museum’s pterosaurs come from the slightly younger Solnhofen limestone, famous for its exquisite preservation of delicate structures. Visitors can examine specimens of Rhamphorhynchus with its distinctive long tail and teeth, and Pterodactylus with its shorter skull and more specialized features. Most impressively, several specimens preserve the delicate wing membranes that allowed these animals to fly, providing crucial information about their aerodynamic capabilities. CT scanning and UV photography techniques used by museum researchers have revealed previously unknown details about pterosaur anatomy, including wing structure, brain morphology, and growth patterns. Interactive exhibits demonstrate how these animals—neither dinosaurs nor birds, but a distinct reptile lineage—conquered the air millions of years before birds evolved flight.

Cutting-Edge Research Behind the Exhibits

Behind the public galleries, Stuttgart’s Natural History Museum functions as an active research institution where paleontologists continue to make groundbreaking discoveries using the latest technology. The museum’s laboratories employ techniques that would have seemed like science fiction just decades ago, including CT scanning to examine the internal anatomy of fossils without damaging them, synchrotron imaging to detect chemical traces of original soft tissues, and digital reconstruction to understand how extinct animals moved. Museum scientists regularly publish findings in top scientific journals, describing new species and revolutionizing our understanding of ancient life. This research extends beyond just describing fossils to addressing larger questions about evolution, extinction events, and ancient climate change. Current projects include investigations into marine reptile locomotion, the diet and feeding behavior of Jurassic predators, and reconstructing ancient marine temperatures using chemical signatures preserved in fossil shells.

The Archeopteryx Connection

While the most famous specimen of Archaeopteryx resides in Berlin, Stuttgart’s museum offers compelling context for understanding this crucial evolutionary link between dinosaurs and birds. Archaeopteryx, discovered in the Solnhofen limestone of Bavaria, lived in the same region and time period as many of the museum’s other specimens, allowing visitors to understand the complete ecosystem in which this transitional creature evolved. The museum’s exhibits place Archaeopteryx within its evolutionary context, showing its relationship to small theropod dinosaurs on one side and early birds on the other. Detailed casts and multimedia presentations highlight the mosaic of features that make Archaeopteryx so significant: feathers and wishbone like a bird, but teeth and a long bony tail like its dinosaur ancestors. These displays reflect the current scientific consensus that birds are, in fact, a surviving lineage of dinosaurs, an evolutionary fact dramatically illustrated by the transitional features preserved in these 150-million-year-old fossils from southern Germany.

Beyond Bones: The Amber Collection

Complementing the Jurassic marine fossils, the museum houses an extraordinary collection of amber specimens that provide glimpses of ancient terrestrial ecosystems. These golden time capsules, formed from the fossilized resin of prehistoric trees, contain perfectly preserved insects, spiders, plant fragments, and occasionally even small vertebrates, trapped and preserved in exceptional three-dimensional detail. While most of the collection features Baltic amber from the more recent Eocene epoch (about 44 million years ago), some specimens date back to the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, offering rare glimpses of terrestrial invertebrates that were contemporaries of the marine creatures found in the Posidonia Shale. Advanced imaging techniques employed by museum researchers have revealed incredible details within these amber pieces, including microscopic structures of insect eyes, pollen grains attached to fossilized bees, and even air bubbles containing samples of ancient atmosphere. The amber collection provides a perfect complement to the marine fossils, helping visitors understand what was happening on land while ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs swam in the nearby seas.

Educational Programs: Bringing Fossils to Life

The museum excels in translating complex paleontological concepts into engaging educational experiences for visitors of all ages. Special programs for school groups incorporate hands-on activities like mock fossil excavations, where students can experience the thrill of discovery while learning scientific methodology. Weekend workshops allow families to explore topics ranging from dinosaur diversity to marine reptile adaptations, often including opportunities to handle real fossils under expert guidance. The museum’s digital offerings have expanded significantly in recent years, with virtual tours, 3D fossil models that can be manipulated online, and educational videos created by the museum’s paleontologists. For more serious enthusiasts, the museum offers citizen science opportunities where volunteers can participate in real research projects, helping to prepare specimens or digitize collection information. These educational initiatives reflect the museum’s commitment to making paleontology accessible and relevant to contemporary audiences while inspiring the next generation of natural scientists.

Conservation Challenges: Preserving the Past for the Future

Maintaining these irreplaceable fossils presents unique conservation challenges that the museum’s staff tackle with specialized expertise. Many specimens from the Posidonia Shale contain unstable minerals like pyrite (fool’s gold) that can deteriorate when exposed to oxygen and humidity, literally causing fossils to crumble over time. The museum employs conservators who monitor specimens for signs of deterioration and apply cutting-edge preservation techniques, including climate-controlled display cases, special coating treatments, and even oxygen-free storage for the most vulnerable items. Digital preservation represents another aspect of the museum’s conservation efforts, with high-resolution photography, 3D scanning, and CT imaging creating digital records of specimens that could potentially serve as research resources even if the physical specimens were damaged. The ethics of fossil collection also present challenges, with the museum working to ensure all new acquisitions are ethically sourced while collaborating with local authorities to prevent illegal fossil trading that threatens scientific heritage around the world.

Visitor Experience: Engaging the Public with Ancient Life

The museum creates a multisensory experience that makes paleontology accessible to visitors regardless of their scientific background. Life-sized reconstructions bring extinct creatures to scale, helping visitors comprehend the actual dimensions of these ancient animals. Interactive touchscreens allow exploration of fossil details too small to see with the naked eye, while augmented reality stations transform skeletal mounts into fully-fleshed creatures that appear to move through the gallery space. Audio guides narrated by museum paleontologists provide expert commentary, sharing the stories behind major discoveries and explaining how scientists interpret fossil evidence. Specially designed lighting highlights the delicate details of the Holzmaden specimens, revealing soft-tissue impressions and other subtle features that might otherwise go unnoticed. The museum regularly refreshes its temporary exhibition spaces, ensuring that even frequent visitors discover something new with each trip, whether it’s recently prepared specimens from the collection or visiting exhibits from partner institutions around the world.

Global Context: How Southern Germany’s Fossils Changed Paleontology

The fossils showcased in Stuttgart’s museum have played a pivotal role in the development of paleontology as a scientific discipline, with many specimens serving as type specimens (the reference examples) for species known worldwide. The exceptional preservation quality of southern German fossils has repeatedly advanced our understanding of extinct animals, revealing details about soft tissues, coloration, and internal anatomy that are rarely preserved elsewhere. The Holzmaden ichthyosaurs were among the first fossils to definitively demonstrate that these marine reptiles gave birth to live young rather than laying eggs, a major biological insight. Similarly, the pterosaur specimens with preserved wing membranes were crucial for understanding how these animals flew, settling long-standing debates about their aerodynamic capabilities. Beyond individual discoveries, the comprehensive ecosystem preservation in the Posidonia Shale has allowed scientists to reconstruct ancient food webs and study predator-prey relationships in detail impossible with more fragmentary fossil assemblages. This scientific legacy continues today, with specimens from the Stuttgart collection regularly featured in research that pushes the boundaries of what we can learn from the fossil record.

Conclusion

Stuttgart’s Natural History Museum stands as a world-class institution where visitors can journey back to the Jurassic period through some of the most spectacularly preserved fossils ever discovered. The museum’s collection tells a comprehensive story of life in southern Germany’s ancient seas and landscapes, from microscopic plankton to massive marine reptiles and early dinosaurs. Beyond merely displaying these paleontological treasures, the museum actively contributes to our evolving understanding of Earth’s history through ongoing research, conservation efforts, and innovative educational programming. For anyone fascinated by prehistoric life, the museum offers an unparalleled opportunity to witness evolutionary history captured in stone, making the distant past tangible and immediate in a way few other institutions can match.