In the annals of paleontology, few stories match the remarkable journey of Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska, a trailblazing Polish scientist who changed our understanding of prehistoric life. Leading groundbreaking expeditions across the harsh Gobi Desert in the 1960s and 1970s, she unearthed fossilized treasures that revolutionized our knowledge of dinosaurs and early mammals. Her discoveries not only enriched science but also broke gender barriers in a male-dominated field during the Cold War era. This is the story of an extraordinary woman whose determination, intellect, and spirit of adventure left an indelible mark on paleontology.

Early Life and Education in Wartime Poland

Born on April 25, 1925, in Sokołów Podlaski, Poland, Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska’s early life was shaped by the turbulent events of World War II. Despite the German occupation of Poland disrupting formal education, she participated in underground classes at the University of Warsaw, risking her life for knowledge at a time when Polish intellectual life was being systematically destroyed. Following the war, she officially enrolled at the University of Warsaw, where she pursued her passion for paleontology with unwavering dedication. Kielan-Jaworowska completed her doctoral studies in 1953, focusing on trilobites, ancient marine arthropods that lived millions of years before dinosaurs. These formative years instilled in her a resilience and determination that would become hallmarks of her scientific career, forging a scholar whose ambitions would not be limited by conventional boundaries or expectations.

The Polish-Mongolian Paleontological Expeditions

Between 1963 and 1971, Kielan-Jaworowska led a series of groundbreaking Polish-Mongolian Paleontological Expeditions that would define her legacy. These ambitious journeys into the Gobi Desert represented one of the most successful international scientific collaborations during the Cold War era. Unlike previous expeditions to the region, which had been predominantly American or Soviet, these Polish-led missions brought a fresh perspective to the field. Navigating political complexities with diplomatic finesse, Kielan-Jaworowska assembled teams of Polish and Mongolian scientists who worked together despite language barriers and cultural differences. The expeditions required meticulous planning to overcome the harsh desert conditions, with teams enduring scorching days, freezing nights, sandstorms, and limited resources. Their perseverance yielded extraordinary rewards, as the Gobi Desert proved to be one of the world’s richest fossil repositories, particularly for Late Cretaceous dinosaurs and early mammals from a critical period in Earth’s history.

Discoveries in the Gobi Desert

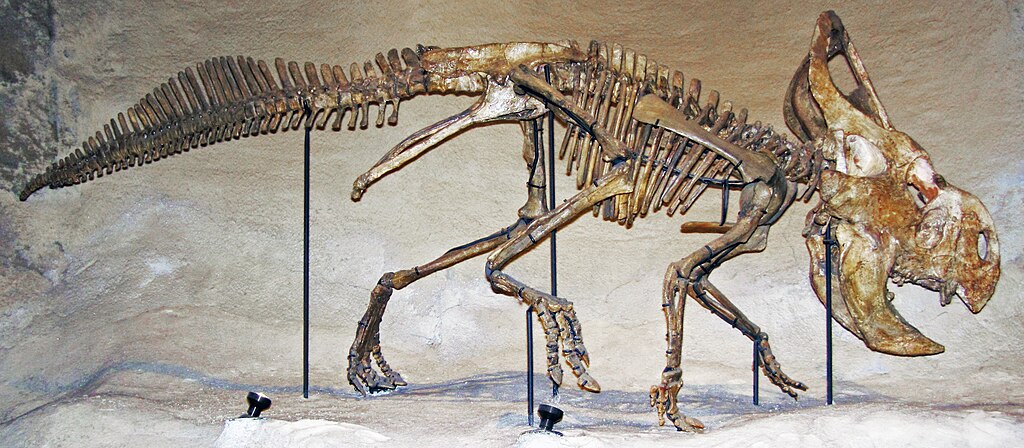

The Gobi expeditions led by Kielan-Jaworowska yielded an astonishing array of dinosaur specimens that significantly expanded our understanding of these prehistoric creatures. Among their most celebrated finds were several specimens of the enigmatic Velociraptor, years before this dinosaur would become a household name through popular culture. The team uncovered the famous “Fighting Dinosaurs” fossil—a Velociraptor and Protoceratops seemingly locked in combat at the moment of their deaths, providing rare evidence of dinosaur behavior. They also discovered numerous specimens of Tarbosaurus (a close relative of Tyrannosaurus rex), Gallimimus (an ostrich-like dinosaur), and various ornithischian dinosaurs. Many of these fossils were remarkably complete and well-preserved due to the unique conditions of the Gobi Desert environment. The expeditions uncovered not just isolated bones but entire skeletons and, in some cases, multiple individuals, offering unprecedented insights into dinosaur anatomy, diversity, and paleoecology during the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 80-70 million years ago.

Pioneer in Mammalian Paleontology

While the dinosaur discoveries garnered significant attention, Kielan-Jaworowska’s most profound scientific contributions came from her work on early mammals. She uncovered extraordinarily rare and well-preserved specimens of Mesozoic mammals—small creatures that lived alongside dinosaurs but remained relatively unknown due to their fragile skeletons rarely fossilizing intact. Her expeditions yielded unprecedented numbers of these specimens, including complete skulls and skeletons of multituberculates, a successful group of rodent-like mammals that survived for over 100 million years. These discoveries were revolutionary because they provided the first detailed glimpse into mammalian life during the Age of Dinosaurs. Through meticulous analysis of these fossils, Kielan-Jaworowska was able to reconstruct aspects of early mammalian anatomy, development, and evolutionary relationships that had previously been the subject of speculation. Her findings fundamentally reshaped scientific understanding of mammalian origins and early diversification, establishing her as the world’s foremost authority on Mesozoic mammals and illuminating a critical chapter in the evolutionary history that eventually led to our species.

Scientific Methods and Innovations

Kielan-Jaworowska pioneered advanced techniques in paleontological research that transformed how scientists study ancient fossils. Recognizing the limitations of traditional methods when examining the minuscule and delicate structures of early mammal skulls, she developed novel approaches for fossil preparation and analysis. She was among the first paleontologists to employ serial grinding techniques, where fossils were ground down microscopically thin layer by layer and photographed to create detailed three-dimensional reconstructions of internal anatomical structures. Her laboratory at the Polish Academy of Sciences became a center for innovation in fossil preparation techniques, attracting researchers from around the world eager to learn her methods. Kielan-Jaworowska also embraced emerging technologies throughout her career, eventually utilizing CT scanning and computer modeling to visualize the brains and sensory systems of extinct mammals. These methodological innovations allowed her to extract unprecedented amounts of biological information from fossil specimens, revealing details about the neuroanatomy, hearing capabilities, and potential behaviors of creatures that had been extinct for over 65 million years.

Breaking Gender Barriers in Science

Kielan-Jaworowska’s achievements took on added significance considering the formidable gender barriers present in mid-20th-century science. As a woman leading major international scientific expeditions during the 1960s, she operated in a realm where female leadership was exceedingly rare. Her command of the Polish-Mongolian expeditions—directing teams predominantly composed of men, coordinating complex logistics, and navigating the political intricacies of international collaboration during the Cold War—challenged prevailing gender norms in both Western and Eastern Bloc scientific communities. Colleagues frequently noted her exceptional combination of scientific rigor, leadership acumen, and diplomatic skill. Rather than conforming to expectations, she created her path, becoming a role model for generations of women in paleontology and geology. Despite facing skepticism and occasional resistance, she earned respect through the undeniable quality of her research and discoveries. Her success helped normalize the presence of women in field-based sciences and expedition leadership, gradually transforming perceptions about gender roles in paleontology.

Academic Career and Global Influence

Kielan-Jaworowska’s academic career extended far beyond fieldwork, as she built a distinguished reputation as a professor, researcher, and scientific leader. After establishing herself at the Polish Academy of Sciences, where she directed the Institute of Paleobiology from 1961 to 1982, her influence expanded globally through visiting professorships at prestigious institutions including Harvard University and the Collège de France. These international appointments allowed her to share her expertise while forging collaborative relationships with scientists worldwide. Her linguistic abilities—she was fluent in several languages—facilitated her role as a scientific bridge-builder between East and West during politically complicated times. Throughout her career, she mentored numerous students who went on to become prominent paleontologists in their own right, extending her scientific legacy through multiple generations of researchers. As a member of scientific academies across Europe and North America, she helped shape research priorities and funding directions in paleontology on an international scale, advocating for greater attention to the study of mammalian evolution and Mesozoic ecosystems.

Landmark Publications and Scientific Legacy

Kielan-Jaworowska’s scientific output was prodigious, with over 220 scientific publications that transformed our understanding of early mammals and their evolution. Her magnum opus, “Mammals from the Age of Dinosaurs,” co-authored with Richard Cifelli and Zhe-Xi Luo in 2004, stands as the definitive reference work on Mesozoic mammals, synthesizing decades of research and establishing the framework for all subsequent studies in the field. This comprehensive volume integrates findings from her Gobi expeditions with global discoveries, creating an unprecedented portrait of mammalian life during the dinosaur era. Beyond her publications on mammals, she authored significant papers on fossil collecting methodologies, paleobiogeography, and extinction patterns. Her meticulous attention to detail, combined with her ability to draw broad evolutionary conclusions from fossil evidence, characterized her scientific approach. She was also known for her willingness to revise her interpretations when new evidence emerged, exemplifying scientific integrity. The taxonomic names she established—including several genera and species of multituberculate mammals—permanently inscribed her discoveries in the scientific record, creating a lasting classification system for these ancient creatures.

Navigating Cold War Politics in Science

The success of the Polish-Mongolian expeditions represented a remarkable achievement in scientific diplomacy during the Cold War era, with Kielan-Jaworowska skillfully navigating complex geopolitical waters. Operating from Poland—a Soviet-aligned country but one with a tradition of intellectual independence—she created a unique scientific enterprise that crossed ideological boundaries. Her expeditions required delicate negotiations with both Mongolian authorities and Soviet officials who traditionally controlled scientific access to Mongolia, which she handled with remarkable diplomatic tact. She maintained professional relationships with Western scientists despite political tensions, ensuring her team’s discoveries became part of the global scientific conversation rather than remaining isolated behind the Iron Curtain. When political circumstances threatened to restrict her work, she displayed remarkable adaptability, finding alternative pathways to continue her research. Despite the constraints of the Communist system, she secured unprecedented resources and permissions for her expeditions through a combination of scientific credibility, personal charisma, and strategic persistence. Her success demonstrated how scientific cooperation could transcend political divides, creating channels of intellectual exchange even during periods of heightened international tension.

Life Beyond the Fossil Record

Beyond her scientific achievements, Kielan-Jaworowska led a rich personal life that informed and complemented her professional pursuits. Her marriage to Zbigniew Jaworowski, a prominent physician and radiation scientist, created a partnership of two distinguished scientific minds who supported each other’s ambitious careers. Colleagues and students often remarked on her well-rounded personality—she was known for her dry wit, her appreciation of literature and art, and her enthusiasm for sharing Polish cultural traditions with international colleagues. Despite the demanding nature of her work, she made time for mentorship, particularly encouraging young women entering paleontology. Her correspondence, preserved in various archives, reveals a scientist who maintained deep friendships across continents and decades, often combining scientific discussions with personal warmth. Those who worked closely with her described a leader who demanded excellence but also showed genuine concern for her team members’ well-being during grueling field expeditions. This human dimension of her character—combining intellectual rigor with personal warmth—helped explain her effectiveness in building the international collaborations that defined her career.

Awards and Recognition

Throughout her long career, Kielan-Jaworowska received numerous prestigious accolades recognizing her exceptional contributions to science. In 1986, she was awarded the Alfred Sherwood Romer Prize from the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, one of the field’s highest honors. The Mongolian government recognized her contributions to their national scientific heritage with the Order of the Polar Star, the country’s highest civilian honor for foreign nationals. She was elected to membership in the Polish Academy of Sciences, the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, and received honorary doctorates from universities across Europe and North America. The paleontological community paid her the distinct honor of naming several fossil species after her, including the multituberculate Kielantherium and the dinosaur Barsboldia kielanae, ensuring her name would be permanently associated with the prehistoric creatures she studied. Despite these accolades, colleagues noted her humility and focus on research rather than recognition. In 2013, near the end of her life, a special volume of international paleontological studies was dedicated to her, with contributions from scientists whose careers she had influenced across multiple generations, demonstrating the extraordinary reach of her scientific legacy.

The Lasting Impact on Modern Paleontology

The scientific ripples from Kielan-Jaworowska’s work continue to influence paleontology well into the 21st century. Her detailed studies of multituberculate mammals provided crucial evidence for understanding how mammals survived the mass extinction that eliminated the non-avian dinosaurs 66 million years ago. Modern paleontologists regularly cite her work when investigating mammalian evolutionary adaptations, brain development, and ecological relationships. The specimens she collected continue to yield new insights as they are reexamined with advanced technologies that weren’t available during her lifetime. The methodological approaches she pioneered for studying tiny fossils have been adapted and expanded by new generations of researchers examining everything from dinosaur embryos to microfossils. Perhaps most significantly, the collaborative international model she established for paleontological expeditions has become standard practice in the field, with multinational teams now regularly working at fossil sites worldwide. Contemporary Mongolian paleontology, now flourishing with native-led research programs, traces much of its institutional foundation to the training and resources provided through her expeditions. This continuing scientific influence ensures that while Kielan-Jaworowska passed away in 2015 at the age of 89, her contributions remain vibrantly alive in current paleontological research.

Conclusion

Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska’s remarkable life journey from war-torn Poland to the dinosaur graveyards of Mongolia exemplifies the power of scientific passion and perseverance. Her groundbreaking discoveries reshaped our understanding of prehistoric life, particularly the small, resourceful mammals that survived in a world dominated by dinosaurs. As both a pioneering woman in science and a masterful diplomat navigating Cold War tensions, she transcended the boundaries of her era. Through her meticulous research, innovative methods, and generous mentorship, she built a legacy that continues to inspire paleontologists worldwide. Kielan-Jaworowska’s story reminds us that the search for knowledge about Earth’s ancient past requires not just scientific brilliance but also courage, adaptability, and a profound commitment to international collaboration—qualities that defined this extraordinary Polish pioneer.