The road to dinosaur dominance wasn’t the quick takeover we might imagine. Picture this: roughly 240 million years ago, when the first dinosaurs appeared, they were just small, nimble creatures scurrying around in a world already ruled by giants. But how did these chicken-sized underdogs eventually become the most successful land animals Earth had ever seen? The answer lies in a dramatic story of survival, extinction, and opportunity that unfolded over millions of years.

The Triassic Period was like nature’s ultimate battlefield. The Triassic was a time of change, a transition from a world dominated by mammal-like reptiles to one ruled by dinosaurs. Yet this transition wasn’t immediate or peaceful. Their main competitors were the pseudosuchians, such as aetosaurs, ornithosuchids and rauisuchians, which were more successful than the dinosaurs. These early dinosaurs had to outmaneuver, outlast, and ultimately outlive an impressive roster of competitors who seemed far better equipped for success.

The Mighty Pseudosuchians: Crocodilian Relatives That Ruled Before Dinosaurs

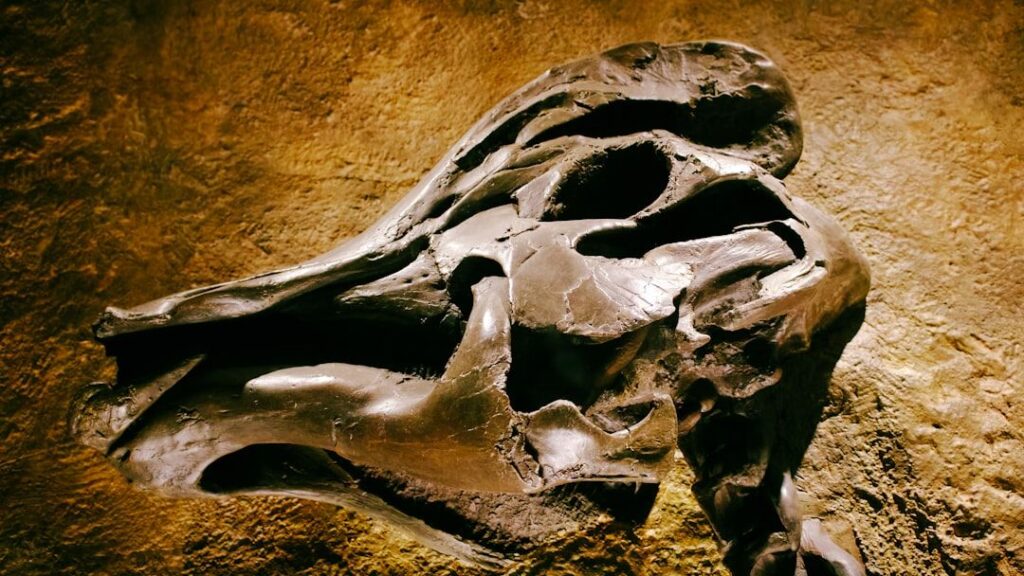

When we think about ancient predators, we often jump straight to T. rex. But long before tyrannosaurs stalked the Earth, there were the pseudosuchians – and they were absolutely terrifying. Early pseudosuchians were successful in the Triassic period. They included giant, quadrupedal apex predators such as Saurosuchus, Prestosuchus, and Fasolasuchus. Ornithosuchids were large scavengers, while erpetosuchids and gracilisuchids were small, light-footed predators.

These weren’t your average reptiles. Pseudosuchians appeared during the late Olenekian (early Triassic); by the Ladinian (late Middle Triassic) they dominated the terrestrial carnivore niches. Their heyday was the Late Triassic, during which time their ranks included erect-limbed rauisuchians, herbivorous armored aetosaurs, the large predatory poposaurs, the small agile sphenosuchian crocodilians, and a few other assorted groups.

The pseudosuchians were essentially the archosaur success story of their time. They had figured out the perfect recipe for domination: diverse body plans, specialized feeding strategies, and the ability to fill multiple ecological niches. While early dinosaurs were still finding their footing, these creatures had already claimed the throne.

Rauisuchians: The Nightmare Predators of the Triassic

If pseudosuchians were impressive, rauisuchians were downright legendary. The rauisuchians were a group of Triassic archosaurs that usually grew between three and thirty-two feet in length and stood between two and a half and nine feet tall. Nowadays the group “Rauisuchia” is considered an evolutionary grade or ‘wastebin taxon’ in that it includes most of the large, predatory carnivorous pseudosuchians that lived during the Triassic Period and which didn’t fall into the crocodylomorpha.

These weren’t just big – they were strategically big. As they grew larger as the millions of years eked by, they became better suited for taking down large prey, such as the tusked dicynodont therapsids that flourished during the Triassic. Towards the Middle and Late Triassic they became the top predators, the terror of Triassic nightmares. Picture creatures like Postosuchus stalking through ancient landscapes, capable of rearing up on their hind legs to scout for prey or delivering devastating crushing blows.

The rauisuchians had cracked the code of being apex predators. They possessed the size, strength, and hunting adaptations that should have guaranteed their success for millions of years to come. Yet they disappeared, leaving behind a vacancy that dinosaurs would eagerly fill.

Phytosaurs: The Crocodile Look-alikes That Mastered Aquatic Hunting

One of evolution’s most fascinating examples of convergent evolution emerged in the form of phytosaurs. Phytosaurs (Φυτόσαυροι in Greek, meaning ‘plant lizard’) are an extinct group of large, mostly semiaquatic Late Triassic archosauriform or basal archosaurian reptiles. Despite their misleading name – they were definitely not plant eaters – these creatures had mastered a lifestyle that would later be perfected by crocodilians.

In fact, phytosaurs looked almost exactly like living crocs. They had short legs, wide, heavy bodies with rows of armored scales, long tails, and long toothy snouts. The only obvious difference between crocodiles and phytosaurs is that crocodiles have their nostrils at the ends of their snouts, and phytosaurs had them on raised hump in front of their eyes.

What made phytosaurs particularly formidable was their specialization. Presumably the narrow-snouted species ate mostly fish and broad-snouted species ate a wider variety of prey. Phytosaur skeletons have been found with the remains of other reptiles in their stomachs, including terrestrial animals like rhynchosaurs (stocky, pig-like herbivores). Phytosaurs may have ambushed land animals when they came down to rivers or water holes to drink, just as living crocodilians attack antelopes and deer. They had essentially cornered the market on semi-aquatic predation. At 12 meters long, the largest phytosaurs were as large or larger than the biggest living crocs, and they were the largest predators of the Triassic Period outside of the ocean-going ichthyosaurs.

Aetosaurs: The Armored Herbivores That Pioneered Plant-Eating Innovation

While carnivorous competitors grabbed headlines, the herbivorous aetosaurs represented a different kind of challenge for early dinosaurs. These weren’t competitors in the traditional predator-prey sense, but rather rivals for the same ecological niche that plant-eating dinosaurs would eventually dominate.

Pseudosuchians comprise mostly extinct Triassic groups such as phytosaurs, aetosaurs, prestosuchids, rauisuchids, and poposaurs. All were carnivorous except the armoured, herbivorous aetosaurs. The aetosaurs had taken a completely different evolutionary path, developing heavy armor plating and specialized feeding adaptations for processing plant material.

What made aetosaurs particularly impressive was their commitment to defense. Unlike many other herbivores of their time, they had evolved comprehensive body armor that could protect them from even the largest predators. They represented a successful alternative strategy to the speed and agility that would later characterize many dinosaurian herbivores. In a world full of massive predators, being a walking tank wasn’t a bad strategy at all.

Dicynodonts: The Tusked Mammal Relatives That Survived the Great Dying

Among all the competitors dinosaurs faced, perhaps none were as resilient or initially successful as the dicynodonts. Dicynodontia is an extinct clade of anomodonts, an extinct type of non-mammalian therapsid. Dicynodonts were herbivores that typically bore a pair of tusks, hence their name, which means ‘two dog tooth’. Members of the group possessed a horny, typically toothless beak, unique amongst all synapsids.

These weren’t small creatures skulking in the shadows. They became globally distributed and the dominant herbivorous animals in the Late Permian, ca. 260–252 Mya. Even more impressively, They were devastated by the end-Permian Extinction that wiped out most other therapsids ca. 252 Mya. They rebounded during the Triassic but died out towards the end of that period.

The dicynodonts had proven their evolutionary staying power by surviving Earth’s worst mass extinction event. They were the most successful and diverse of the non-mammalian therapsids, with over 80-90 genera known, varying from rat-sized burrowers to elephant-sized browsers. Some, like the recently discovered Lisowicia, was about the size of a modern-day elephant, about 4.5 metres long, 2.6 metres high and weighed approximately 9 tons, which is 40 percent larger than any previously identified dicynodont. These giants were direct competitors with early sauropodomorph dinosaurs for the same ecological niches.

Cynodonts: The Dog-Toothed Ancestors of Modern Mammals

If any group seemed destined for long-term success, it was the cynodonts. Cynodontia (from Ancient Greek κύων (kúōn) ‘dog’ and ὀδούς (odoús) ‘tooth’) is a clade of eutheriodont therapsids that first appeared in the Late Permian (approximately 260 mya), and extensively diversified after the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Mammals are cynodonts, as are their extinct ancestors and close relatives (Mammaliaformes), having evolved from advanced probainognathian cynodonts during the Late Triassic.

What made cynodonts particularly formidable competitors was their advanced physiology. The cynodonts had begun to develop the characteristics that today are exclusive to mammals: they were warm-blooded and had hairy bodies and various types of teeth. They had essentially achieved what we might consider a “modern” metabolic advantage millions of years before dinosaurs developed similar capabilities.

The group of cynodonts that became most extensively diversified in the Middle Triassic was the transversodontids. Unlike other cynodonts, which were generally carnivorous or omnivorous, transversodontids were herbivores. Their teeth were specialized for eating roots, leaves or any other plant matter that was available in the hot, semiarid climate that predominated in the interior of Pangaea. They had diversified into multiple ecological niches and seemed perfectly positioned for long-term success.

Rhynchosaurs: The Barrel-Bodied Plant Processors

Completing the roster of major dinosaur competitors were the rhynchosaurs – stocky, pig-like herbivores that had mastered the art of plant processing in ways that early dinosaurs simply couldn’t match. Phytosaur skeletons have been found with the remains of other reptiles in their stomachs, including terrestrial animals like rhynchosaurs (stocky, pig-like herbivores).

These weren’t the most glamorous creatures, but they were incredibly successful at what they did. By the Carnian they had been supplanted by traversodont cynodonts and rhynchosaur reptiles. During the Norian (middle of the Late Triassic), perhaps due to increasing aridity, they drastically declined, and the role of large herbivores was taken over by sauropodomorph dinosaurs.

The rhynchosaurs represented a completely different approach to herbivory than what dinosaurs would later develop. Where dinosaurs would eventually rely on sophisticated dental batteries or gastroliths for processing plant material, rhynchosaurs had evolved their own unique solutions. The transversodontids had to compete for food with the other large herbivores of the period – the dicynodonts, which were related to the cynodonts but did not have mammalian features, and the rhynchosaurs, which were reptiles. They were direct competitors for the same plant resources that herbivorous dinosaurs would need to survive and thrive.

The Great Extinction: Nature’s Reset Button

So how did dinosaurs overcome such impressive competition? The answer isn’t that they outcompeted these groups in direct confrontation. Instead, they got incredibly lucky. The end-Triassic extinction caused the extinction of all the pseudosuchians with the exception of Sphenosuchia and Crocodyliformes (both Crocodylomorpha), the latter being the ancestors of modern-day crocodiles.

Most of these other animals became extinct in the Triassic, in one of two events. First, at about 215 million years ago, a variety of basal archosauromorphs, including the protorosaurs, became extinct. This was followed by the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event (about 201 million years ago), that saw the end of most of the other groups of early archosaurs, like aetosaurs, ornithosuchids, phytosaurs, and rauisuchians.

The end-Triassic extinction was particularly devastating to dinosaur competitors. The end of the period was marked by yet another major mass extinction, the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event, that wiped out many groups, including most pseudosuchians, and allowed dinosaurs to assume dominance in the Jurassic. This wasn’t survival of the fittest in the traditional sense – it was more like being the last one standing after a natural disaster.

Opportunistic Rise: How Dinosaurs Inherited the Earth

What happened next was less about dinosaur superiority and more about dinosaur opportunity. These groups then became extinct and dinosaurs replaced them and radiated rapidly (opportunism, latest Triassic). The late Triassic extinctions may be linked with floral and climatic changes.

These losses left behind a land fauna of crocodylomorphs, dinosaurs, mammals, pterosaurians, and turtles. The first few lines of early dinosaurs diversified through the Carnian and Norian stages of the Triassic, possibly by occupying the niches of the groups that became extinct.

Rather than winning through direct competition, dinosaurs succeeded through what paleontologists call “opportunistic ecological replacement.” The concepts of differential survival (“competitive”) and opportunistic ecological replacement of higher taxonomic categories are contrasted (the latter involves chance radiation to fill adaptive zones that are already empty), and they are applied to the fossil record.

The Long Game: Why Dinosaurs Ultimately Succeeded

Once dinosaurs got their break, they made the most of it. These extinctions within the Triassic and at its end allowed the dinosaurs to expand into many niches that had become unoccupied. Dinosaurs became increasingly dominant, abundant and diverse, and remained that way for the next 150 million years. The true “Age of Dinosaurs” is during the following Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, rather than the Triassic.

What’s fascinating is how quickly they adapted to their new opportunities. The earth went through a series of violent changes, ultimately wiping out all those rival lineages. Those chicken- and dog-sized dinosaurs survived, thrived, and evolved into the giants we think of today. Dinosaurs ruled the earth for many millions of years, but only after a mass extinction took out most of their rivals.

The dinosaurs didn’t win through being the strongest or most advanced initially. They won by being adaptable survivors who could rapidly diversify once given the chance. Their success story is less about conquest and more about resilience and opportunity.

Conclusion

The rise of dinosaurs wasn’t the inevitable triumph of superior beings, but rather a masterclass in evolutionary opportunism. These seven rival groups – pseudosuchians, rauisuchians, phytosaurs, aetosaurs, dicynodonts, cynodonts, and rhynchosaurs – each seemed better equipped for long-term success than the small, seemingly unremarkable early dinosaurs. They had size, specialized adaptations, proven track records, and in some cases, advanced physiologies that wouldn’t seem out of place in modern animals.

Yet nature had other plans. The end-Triassic extinction event reshuffle the evolutionary deck, eliminating most of dinosaurs’ established competitors and leaving vast ecological niches wide open. What followed wasn’t a story of the strong defeating the weak, but of the adaptable outlasting the specialized. The dinosaurs’ ultimate 150-million-year reign began not with a roar, but with the whisper of opportunity in a world suddenly emptied of its former rulers.

Did you expect that the mighty dinosaurs actually started as underdogs who got lucky?