Picture the most catastrophic disaster Earth has ever witnessed. It wasn’t a comet from space or even a nuclear war – it happened 252 million years ago when volcanic hellfire from Siberia literally cooked the planet. The Permian–Triassic extinction event, colloquially known as the Great Dying, was an extinction event that occurred approximately 251.9 million years ago (mya), at the boundary between the Permian and Triassic geologic periods, and with them the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras. It is Earth’s most severe known extinction event, with the extinction of 57% of biological families, 83% of genera, 81% of marine species, and 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species. From this apocalyptic wasteland emerged the ancestors of creatures that would dominate our planet for the next 160 million years. But here’s the twist – they didn’t win through superiority. They simply got incredibly, outrageously lucky.

The Great Dying: When Life Almost Hit the Reset Button

Whatever happened during the Permian-Triassic period was much worse: No class of life was spared from the devastation. Trees, plants, lizards, proto-mammals, insects, fish, mollusks, and microbes — all were nearly wiped out. Roughly 9 in 10 marine species and 7 in 10 land species vanished. The scale of this extinction makes today’s environmental concerns seem like a minor hiccup in comparison.

Long before dinosaurs, our planet was populated with plants and animals that were mostly obliterated after a series of massive volcanic eruptions in Siberia. Fossils in ancient seafloor rocks display a thriving and diverse marine ecosystem, then a swath of corpses. Some 96 percent of marine species were wiped out during the “Great Dying,” followed by millions of years when life had to multiply and diversify once more. The very air itself became poisonous as toxic gases filled the atmosphere.

Life in the Slow Lane: The Recovery That Took Forever

Life on Earth took about 10 million years to recover fully from the devastation. The Permian-Triassic extinction event reset Earth’s ecosystems. That’s longer than humans have existed as a species, stretched out across geological time that makes our entire civilization look like a blink of an eye.

The early Triassic landscape was eerily quiet compared to the bustling ecosystems of today. Lystrosaurus, the synapsid that inherited the barren world of the Triassic, stared out empty-eyed. With its competition gone, Lystrosaurus spread across the world, from Russia to Antarctica. These pig-sized creatures were essentially the ecological equivalent of that one person left standing after everyone else leaves the party – suddenly they owned the place.

The Mammal-Like Rulers Before the Storm

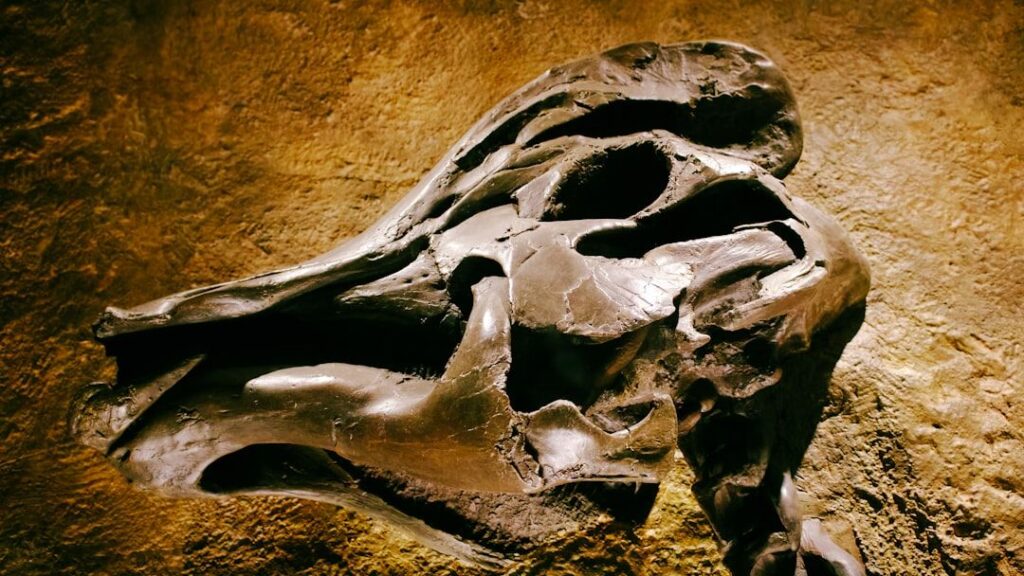

Before dinosaurs ever existed, Earth belonged to creatures called synapsids or therapsids – the mammal-like reptiles that looked like something from a fever dream. The late Permian rocks we passed as we neared Lootsberg Pass capture the synapsids at the height of their reign. For more than 60 million years they were Earth’s dominant land vertebrates, occupying the same ecological niches as their successors, the dinosaurs. These weren’t your typical lizards – some had saber teeth, others had elaborate sails on their backs.

Prior to 251 million years ago, the dominant, large animals on land were the therapsids, early forerunners to mammals. These shrew- to hippo-size creatures came in a variety of forms, from tubby, tusked herbivores to agile, saber-toothed predators. They ruled with an iron fist for millions of years, completely unaware that their days were numbered by volcanic catastrophe brewing in distant Siberia.

The Archosauromorph Underdogs Enter the Scene

Many therapsids disappeared, and the few, diminutive lineages that survived faced competition from a different sort of creature – the archosauromorphs. These reptiles, the precursors of dinosaurs, crocodiles, and their closest relatives, would quickly rise to dominance. But here’s the kicker – they weren’t necessarily better than what came before.

The secret weapon of these early dinosaur relatives wasn’t superior intelligence or stronger teeth. One reason may be that archosauromorphs simply grew and bred faster. The quicker growth rate of the archosauromorphs, which had been discovered in previous studies of dinosaurs and their relatives, meant that these animals reached sexual maturity relatively earlier than the therapsids. Faster growth and breeding meant that the archosauromorphs quickly spread and adapted to overtake available habitats and the ecological roles of large herbivores and big predators before the smaller, slower-growing therapsids had a chance to put up a fight. It was like being first in line at a Black Friday sale – timing was everything.

The Lucky Break That Changed Everything

Instead, he suggests that the dinosaurs’ success hinged on a combination of “good luck” and perseverance. Both they and the crurotarsans survived an extinction event 228 million years ago, which wiped out many other reptile groups like the rhynchosaurs. This wasn’t a story of the best and brightest rising to the top – it was pure chance that these particular lineages happened to survive when so many others perished.

At the end of the Triassic period, some 28 million years later, the dinosaurs weathered another (much bigger) extinction event that finally killed the majority of crurotarsans off for good. It’s not clear why the dinosaurs persevered and the crurotarsans didn’t. Perhaps the dinos had some unique adaptation that the crurotarsans lacked, which ensured their survival. But Brusette says that this explanation is “difficult to entertain” because the crurotarsans were more abundant at the time and had vastly more varied bodies. He also says that the death of certain groups during mass extinctions is more likely to be due to random factors rather than any specific aspect of their lifestyles. In other words, they won the evolutionary lottery.

The Humble Beginnings of Future Giants

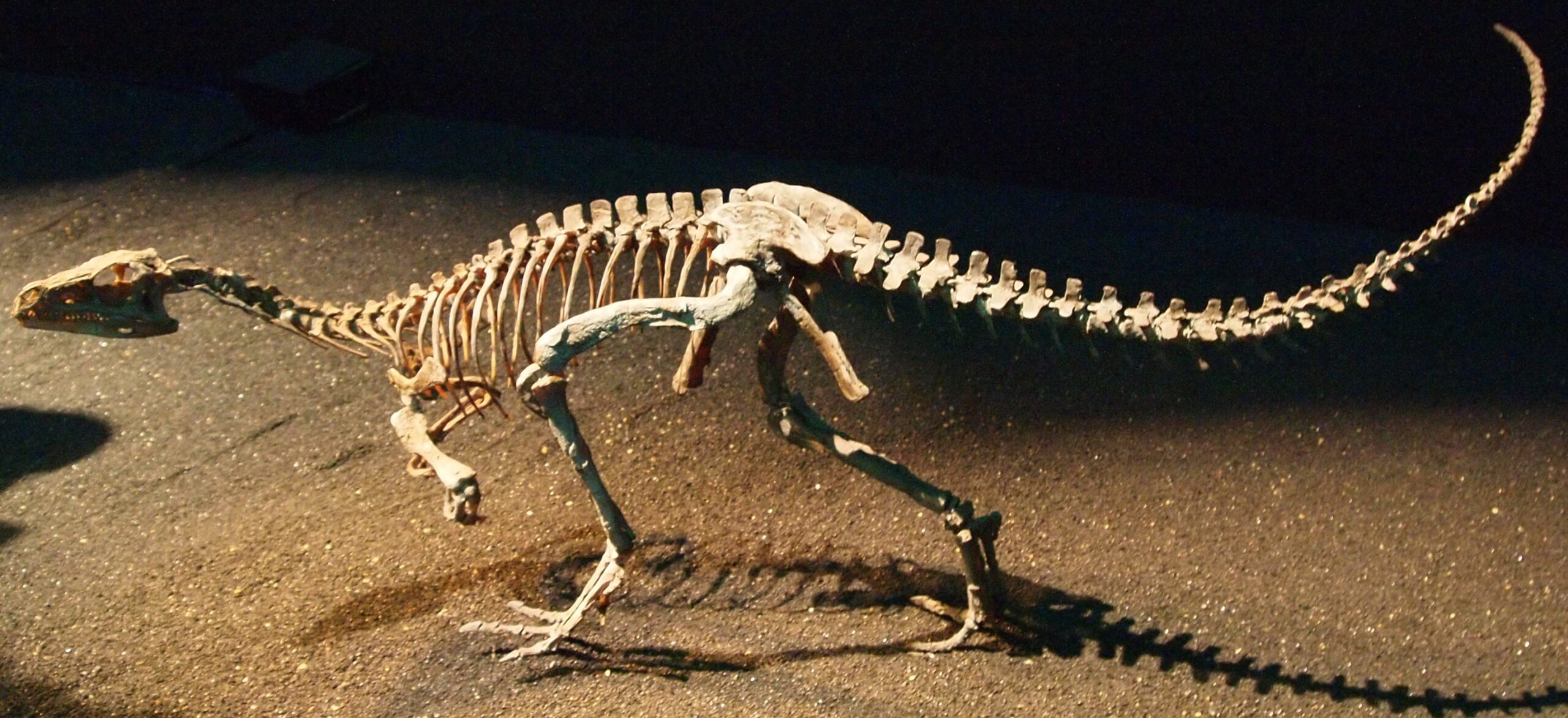

The ancestors of dinosaurs were one of several groups of reptiles that benefited from the Permian–to–Triassic extinction approximately 252 million years ago. These ancestors were lightly built two-legged animals, around the size of a crow. These weren’t the towering monsters we imagine from movies – they were more like feathered chickens running around a devastated landscape.

The first definitive dinosaurs appear in the fossil record around 230 million years ago, though some early forms may date to 240 million years ago. These dinosaurs were small, bipedal creatures that would have darted across the variable landscape. They were bit players in an ecosystem still dominated by other groups, quietly waiting in the wings for their moment to shine. It is probable that they were either carnivores or omnivores, but they definitely were not herbivores. They were relatively uncommon, as even when you get the first definitive dinosaurs around 230 million years ago they are still rare members of the fauna.

The Triassic World: A Planet in Recovery Mode

At the beginning of the Triassic, virtually all the major landmasses of the world were collected into the supercontinent of Pangea. Terrestrial climates were predominately warm and dry (though seasonal monsoons occurred over large areas), and the Earth’s crust was relatively quiescent. Imagine a world where you could theoretically walk from what would become New York to Beijing without ever seeing an ocean.

Much like today, the environments on Pangea were hugely varied. There were parts of the world would have been moist and others that would have been arid. The global effect of this supercontinent would have been a greatly enhanced seasonality in different parts of it. There would likely have been an extremely arid interior, but also some very moist and wet temperate and tropical environments too. This patchwork of environments created opportunities for different groups to carve out their own ecological niches.

The Competition That Dinosaurs Couldn’t Beat

While dinosaurs were still finding their feet, other groups were absolutely thriving. During the Triassic period, the crurotarsans (which eventually gave rise to today’s crocodiles and alligators) were at their most diverse. They ranged from top predators like Postosuchus to the armoured aetosaurs like Desmatosuchus to swift, two-legged runners like Effigia and Shuvosaurus. Many of them were incredibly similar to the dinosaurs we know and love (see bottom image) and some were even mistaken for dinosaurs when they were first discovered. These strikingly similar bodies suggest that members of the two groups shared similar lifestyles and probably competed for the same resources.

If dinosaurs really outcompeted the crurotarsans, you would expect to see the former group evolving at increasing rates during the Triassic, while the latter group’s rate of evolution slowed. But that’s not what happened. Instead, Brusette found that during the Triassic as a whole, the crurotarsans were keeping pace with the expansion of the dinosaur lineage. And surprisingly, the crurotarsans had about twice as much disparity as the dinosaurs did at the time. The crurotarsans were winning by every measurable standard – until they suddenly weren’t.

The Big Break: When Opportunity Finally Knocked

The end of the period was marked by yet another major mass extinction, the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event, that wiped out many groups, including most pseudosuchians, and allowed dinosaurs to assume dominance in the Jurassic. This was the moment everything changed – not through conquest, but through survival.

It would not be until the end-Triassic extinction event that occurred 201 million years ago that dinosaurs would finally get their chance. The mass extinction wiped out almost all the other competing archosaurs, meaning that the environment was left wide open for the dinosaurs to fill. During the Jurassic and the Cretaceous the dinosaurs took full advantage of this, evolving into an incredible array of creatures. It was like inheriting a mansion when everyone else in the neighborhood mysteriously vanished overnight.

The Secret Advantages Hidden in Plain Sight

Dinosaurs stand with their hind limbs erect in a manner similar to most modern mammals, but distinct from most other reptiles, whose limbs sprawl out to either side. This posture is due to the development of a laterally facing recess in the pelvis (usually an open socket) and a corresponding inwardly facing distinct head on the femur. Their erect posture enabled early dinosaurs to breathe easily while moving, which likely permitted stamina and activity levels that surpassed those of “sprawling” reptiles. Erect limbs probably also helped support the evolution of large size by reducing bending stresses on limbs. This wasn’t obvious at the time, but it would prove crucial for their future success.

Not all of the archosauromorphs were large – over time, they diversified into a variety of body sizes throughout the Triassic and Jurassic, from the relatively tiny feathered dinosaur Anchiornis to Apatosaurus and Diplodocus, some of the biggest creatures to ever walk the planet. A key to evolving into such a wide range of sizes, Sookias says, may be in specialized features such as air pockets inside dinosaur bones that reduced the weight. These weren’t advantages that helped them dominate the Triassic – they were evolutionary investments that would pay off later.

The Lottery Ticket That Paid Off Big

Whatever the answer, the sudden volte face of the crurotarsans, from ruling reptiles to evolutionary footnotes, gave the dinosaurs their chance. They were the reptilian equivalent of videotapes, rising to dominance in the wake of a superior Betamax technology. In the brave, new world of the Jurassic, they could exploit the niches vacated by their fallen competitors. Sometimes being second best is exactly what you need – as long as you’re the one left standing when the dust settles.

The rise of the dinosaurs is often spoken of as a single event but it was more likely to have been a two-stage process. The predecessors of the gigantic, long-necked sauropods expanded into new species after the late Triassic extinction, while the big meat-eaters and the armoured plant-eaters only came to the fore as a second extinction heralded the start of the Jurassic. Brusette refers to the dinosaurs as the “beneficiaries of two mass extinction events”, which is ironic given what happened next.

What makes this story truly remarkable is how completely it overturns our assumptions about success and dominance in nature. About a 130 million years later, the dinosaurs’ luck proved to be finite. They ruled the Earth not because they were inherently superior, but because they happened to be in the right place at the right time – twice. Their reign ended the same way it began: with a stroke of cosmic bad luck that cleared the stage for the next act. Sometimes evolution isn’t about survival of the fittest – it’s about survival of the luckiest. Did you ever think that the mighty T-Rex owed its existence to pure chance?