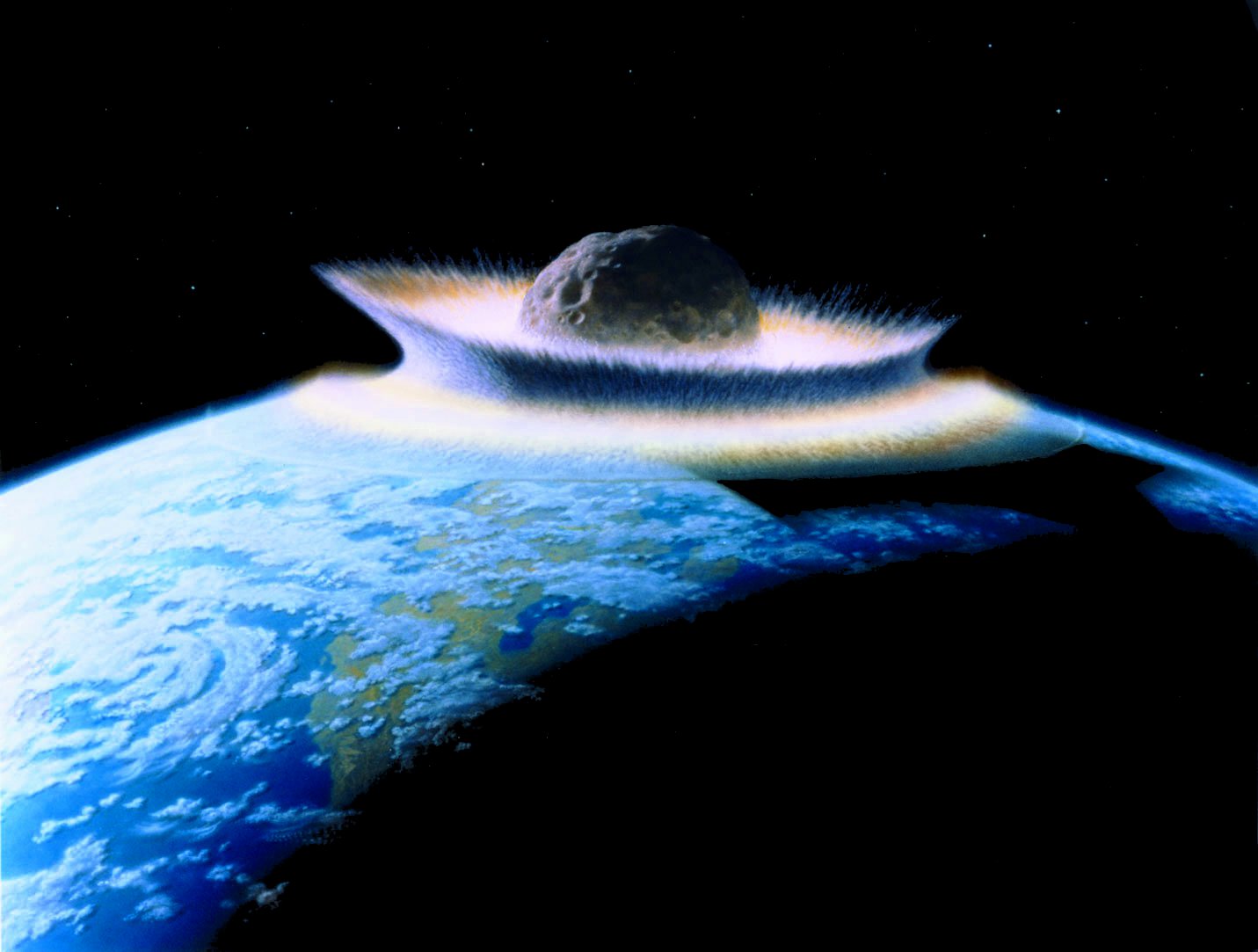

The story of our planet’s most dramatic transformation began with a catastrophic collision that forever changed the course of life on Earth. Picture this: sixty-six million years ago, an asteroid approximately ten kilometers in diameter hurtled toward our planet at incredible speed, ultimately striking what is now Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. This wasn’t just another space rock – it was the catalyst for the most significant evolutionary revolution in mammalian history.

What happened next reads like a science fiction novel, except it’s all terrifyingly real. The impact struck with the force of more than a billion nuclear bombs, punching a hole in Earth’s crust more than ten miles deep and creating tsunamis, wildfires, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions that raged around the planet. Dust and soot clogged the atmosphere, turning the world dark for years. Yet from this apocalyptic devastation emerged the greatest mammalian success story ever told.

The Discovery of Earth’s Most Famous Scar

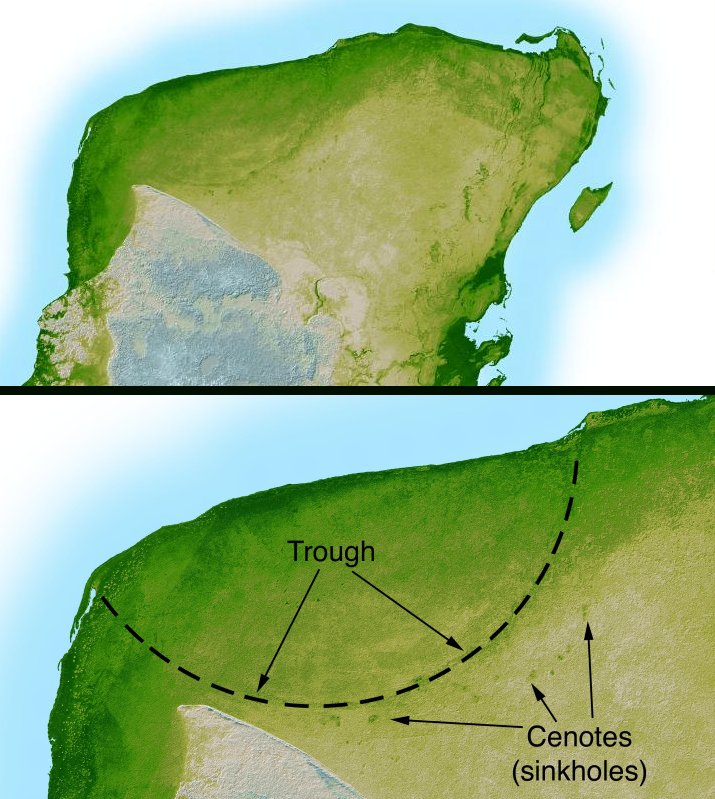

The crater was discovered by Antonio Camargo and Glen Penfield, geophysicists who had been looking for petroleum in the Yucatán Peninsula during the late 1970s. What they stumbled upon was far more valuable than oil – they had found the smoking gun of one of Earth’s most pivotal moments.

The crater is estimated to be 180 kilometers in diameter and 20 kilometers in depth, making it one of the largest impact structures on our planet. Even more remarkable, the crater has an impact ring structure of about 180 kilometers in diameter. This massive scar beneath Mexico’s surface tells a story of planetary transformation that scientists are still unraveling today.

The Moment Everything Changed

Imagine the scene on that fateful day. About 66 million years ago, a large asteroid came rushing out of space at a velocity of more than 25 kilometers per second, generating energy equivalent to 10 thousand times the world’s nuclear arsenal. The impact was so violent that it ejected massive quantities of material into the atmosphere.

A cloud of hot dust, ash and steam spread from the crater, with as much as 25 trillion metric tons of excavated material being ejected into the atmosphere. Some material escaped orbit while some fell back to Earth, and the rock heated Earth’s surface and ignited wildfires estimated to have enveloped nearly 70% of the planet’s forests. This was truly the worst day in Earth’s history, yet it set the stage for mammalian dominance.

The Great Dying – But Not for Everyone

The Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event was a mass extinction of three-quarters of plant and animal species on Earth, including all non-avian dinosaurs. The planet’s dominant rulers for over 160 million years simply vanished, leaving behind a world ripe for new evolutionary experiments.

But here’s where the story gets fascinating. Somehow mammals survived, thrived, and became dominant across the planet, with while many mammals being wiped out alongside the dinosaurs, there was also an increase in the diversity and abundance of those that did survive. The key to their success wasn’t just luck – it was their small size and adaptable nature that would soon prove invaluable in the post-impact world.

Life in the Shadows No More

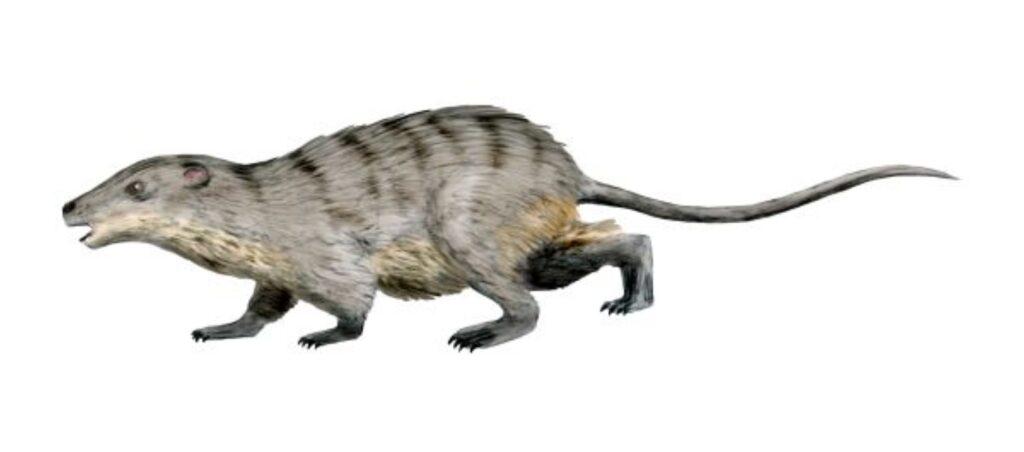

For millions of years, mammals lived like fugitives in their own world. Dinosaurs became giants and excluded mammals from large-bodied niches, while mammals did the opposite: with their small body sizes, they could exploit ecological niches that the bigger dinosaurs couldn’t access. They were the ultimate underdogs, scurrying in the shadows while giants ruled above.

The most fundamental change was the emergence of diurnal mammals active during the daytime, after they had been confined to more furtive nocturnal foraging or hunting by the dominance of the dinosaurs. Suddenly, the world’s day shift had an opening, and mammals were ready to fill it. This transition from night to day living marked the beginning of their incredible evolutionary journey.

Size Matters – The Great Mammalian Expansion

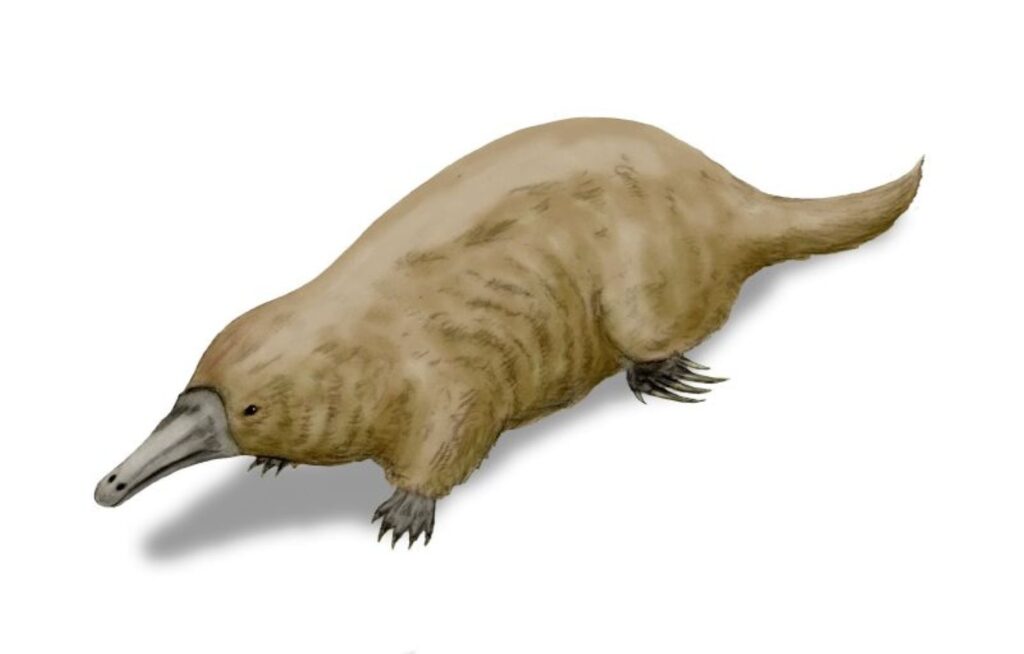

What happened next defies everything we thought we knew about mammalian evolution. The mammals that survived the mass extinction and emerged into the Paleocene world weighed only about a pound, but as thick forests full of ecological opportunity sprung up, some mammals started to grow larger. This wasn’t a gradual process – it was evolutionary overdrive.

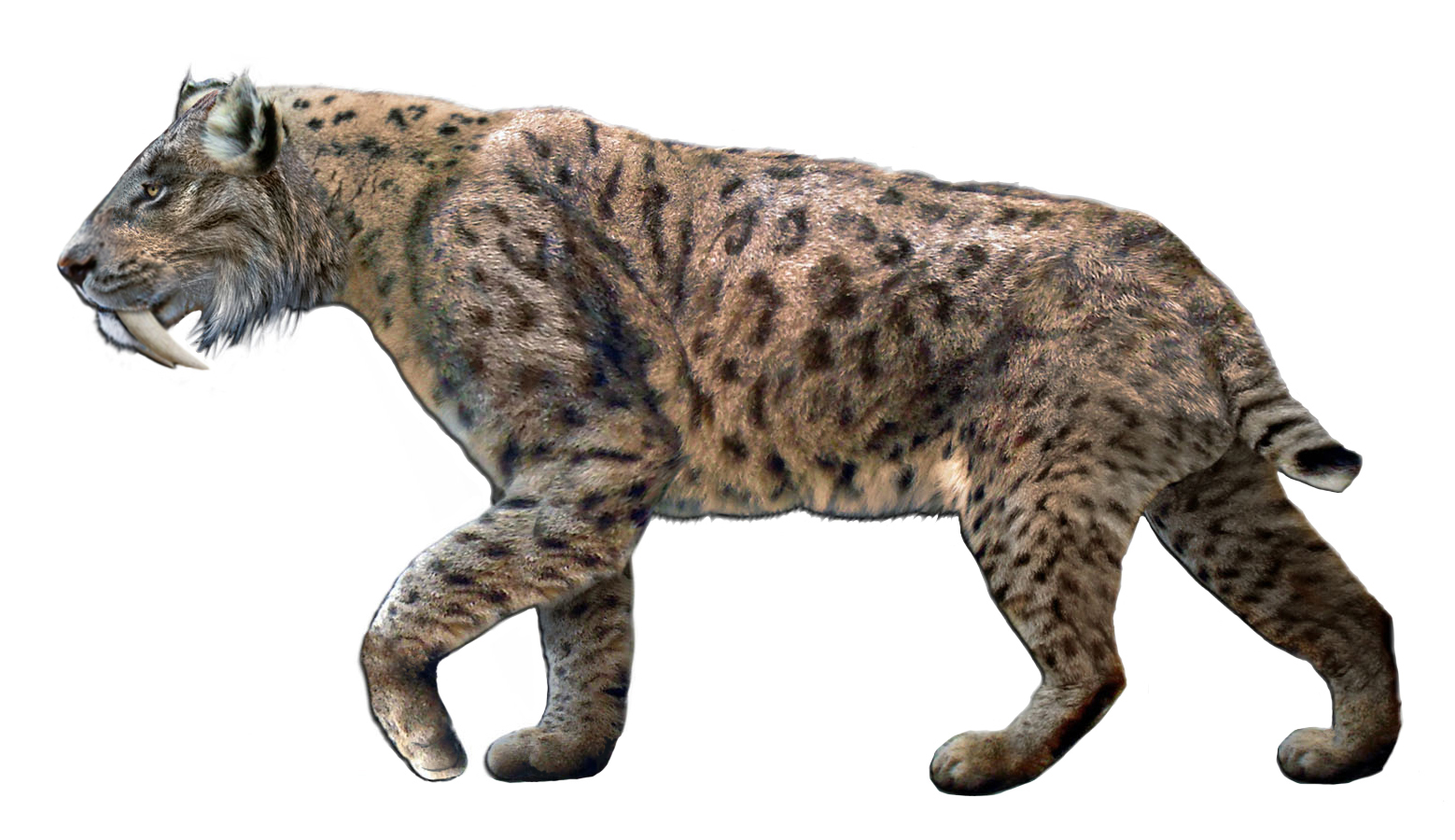

Within mammalian genera, new species were approximately 9.1% larger after the extinction boundary, and after about 700,000 years, some mammals had reached 50 kilos, a 100-fold increase over the weight of those which survived the extinction. To put this in perspective, imagine a house cat suddenly growing to the size of a horse – that’s the scale of transformation we’re talking about.

Brains Versus Brawn – An Unexpected Discovery

Here’s where the story takes a surprising twist that challenged decades of scientific thinking. A new study shows that in the first 10 million years following the mass extinction event, mammals bulked up rather than evolving bigger brains to adapt to dramatic changes. This finding completely overturned the conventional wisdom about mammalian evolution.

Detailed CT scans revealed that the relative brain sizes of mammals at first decreased as their body size unexpectedly increased at a much faster rate, with results suggesting the animals relied heavily on their sense of smell while their vision and other senses were less well developed. It turns out that in the post-dinosaur world, being big was more important than being brilliant – at least initially.

The Paleocene Explosion

New analysis of the fossil record shows that placental mammals became more varied in anatomy during the Paleocene epoch – the 10 million years immediately following the extinction event. This period represents one of the most dramatic evolutionary radiations in Earth’s history.

Mammals evolved a greater variety of forms in the first few million years after dinosaurs went extinct than in the previous 160 million years of mammal evolution, with studies showing that within about 10 million years of the Cretaceous extinction, some 130 genera of mammals existed. The speed of this transformation is mind-boggling when you consider the geological timescales involved.

New Species Rising from the Ashes

The fossil evidence tells an incredible story of rapid diversification. These prehistoric mammals roamed North America during the earliest Paleocene Epoch, within just a few hundred thousand years of the boundary that wiped out the dinosaurs, suggesting mammals diversified more rapidly after the mass extinction than previously thought.

Recent discoveries include creatures that differ in size, ranging up to a modern house cat – much larger than the mostly mouse to rat-sized mammals that lived alongside dinosaurs, with access to different foods and environments enabling mammals to flourish and diversify rapidly in their tooth anatomy. These weren’t just bigger versions of existing mammals – they were entirely new evolutionary experiments.

Environmental Drivers of Change

The transformation wasn’t just about removing dinosaurs from the equation. After the extinction of dinosaurs, volcanoes sparked small temperature increases that coincided with spikes in evolution, with these warming intervals likely playing a role in the rapid evolution and re-diversification of ecosystems post-extinction.

A shift in vegetation took place in the last 10 million years of the Cretaceous period when flowering plants started becoming more commonplace than conifers and ferns, making the animals’ habitat more complex since deciduous trees have an elaborate canopy and understory. This created new ecological niches that mammals could exploit in ways previously impossible.

Competition and Survival Strategies

When dinosaurs went extinct, competitors and predators of mammals disappeared, meaning that pressure limiting what mammals could do ecologically was removed, and they clearly took advantage through rapid increases in body size and ecological diversity. The playing field was suddenly wide open for the first time in millions of years.

Smaller mammals seemed better equipped to survive since they could hide more easily, and those with diverse diets were able to adapt more quickly, though there isn’t one magic reason why some lived and others died – there was probably chance and randomness involved because things changed so quickly after the asteroid hit. Success required both preparation and luck in equal measure.

The Dawn of Modern Mammalian Groups

Within the rapid diversification, bats, primates, rodents, whales and other forerunners of today’s animals were already present by the end of the period. These weren’t primitive versions – many were remarkably sophisticated creatures that would form the foundation of modern mammalian diversity.

Some of today’s familiar mammals, like the groups that later evolved into horses or bats, got their start soon after the extinction and probably as a direct result of it. The asteroid impact didn’t just create an opportunity – it actively drove the evolution of the mammalian groups we see dominating ecosystems today.

Conclusion

The story of ancient craters and the rise of mammals reads like the ultimate underdog tale, except it’s written in stone and preserved in fossils spanning millions of years. The asteroid impact was apocalyptic and changed the course of Earth’s history, with three out of every four species succumbing to extinction. Yet from this devastation emerged one of evolution’s greatest success stories.

What makes this tale so remarkable isn’t just the scale of destruction, but the incredible speed of recovery and innovation that followed. Mammals went from small, nocturnal creatures living in the shadows to the dominant life forms on Earth in a geological blink of an eye. They didn’t just survive the apocalypse – they used it as a launching pad to evolutionary greatness.

The Chicxulub crater remains buried beneath Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, a silent testament to the day everything changed. But its legacy lives on in every mammal walking, swimming, or flying on our planet today. From the tiniest shrew to the largest whale, from our closest primate relatives to our beloved pets, they all owe their existence to that catastrophic moment sixty-six million years ago.

Who would have thought that the worst day in Earth’s history would become the first day of the Age of Mammals?