Picture yourself standing on the shore of a vast ocean some 100 million years ago. The water looks inviting, but beneath its seemingly calm surface lurks a nightmare that would make modern shark encounters seem like a day at the beach. What makes the Cretaceous sea worse than any other in history is that there isn’t just one predator to worry about. There was a whole collection of them, including sharks, lightning-fast killer fish and fearsome giant marine reptiles called mosasaurs.

The Temperature Trap: Bathwater That Burns

The first thing that would shock you about swimming in Cretaceous waters isn’t the predators – it’s the temperature. Late Cenomanian sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Atlantic Ocean were substantially warmer than today (~27-29 °C). Turonian equatorial SSTs are conservatively estimated based on δ18O and high pCO2 estimates to have been ~32 °C, but may have been as high as 36 °C. That’s roughly between 80 and 97 degrees Fahrenheit, making some Cretaceous seas as hot as a comfortable hot tub.

Mean annual temperatures at the poles during the MKH exceeded 14 °C. Even the Arctic waters were warmer than many modern tropical seas. While this might sound pleasant for a swim, these extreme temperatures created unique challenges that could quickly turn deadly for an unprepared swimmer.

Monsters of the Deep: The Apex Predator Paradise

Towards the end of the Cretaceous, the giant mosasaurs were undoubtedly the top predators. Genus like Tylosaurus grew towards 50 feet in length. Imagine encountering a creature longer than a city bus with jaws that could crush a small car. These weren’t just oversized lizards – they were perfectly evolved killing machines that dominated the oceans.

Some developed bulbous teeth that they used to hammer away at oyster-like bivalves, while others developed razor-like teeth that could pierce and shred larger prey, including other mosasaurs. The diversity of hunting strategies meant there was literally nowhere to hide. Whether you stayed near the surface or dove deep, these predators had evolved to hunt in every corner of their aquatic domain.

Lightning-Fast Death: Xiphactinus the Bulldog Fish

Carnivorous fishes like Xiphactinus were the most numerous predators in the Late Cretaceous seas. Picture a fish nearly 20 feet long with a mouth that could swallow a grown person whole, and you’re getting close to understanding the terror that was Xiphactinus. While exact speeds are unknown, its streamlined body suggests it was capable of rapid bursts of speed for ambush predation. This speed offered little chance of seeing this fish coming, and even less of a chance of getting away if you did.

The sheer speed of these predators fundamentally changed the rules of ocean survival. Unlike modern great whites that hunt with stealth and precision, Xiphactinus was built for pure speed and overwhelming force. Your only warning might be a flash of silver before those massive jaws clamped down.

The Shallow Water Nightmare: Where Safety Becomes Danger

You might think staying in shallow water would offer some protection, but the Cretaceous had evolved predators specifically for this strategy. Most lived in shallow waters, but some, like the Tylosaurus, traveled far offshore and dove to deeper depths. The massive mosasaurs weren’t confined to the deep ocean – they actively hunted in the very areas where a modern swimmer might feel safest.

Flightless and unable to walk properly, they spent most of their time at sea hunting fish and squid. They would come on to land to mate and lay eggs. Around the coasts of North America, huge colonies of this seabird congregated to mate. Even the birds weren’t safe, constantly running what one expert described as “a lethal gauntlet” just to find food.

The Chemistry of Death: Ocean Anoxic Events

Beyond the living threats, the Cretaceous oceans themselves could be deadly. However, during the Jurassic and early Cretaceous episodes local anoxia occurred and this state developed into a global scale phenomenon during the mid-Cretaceous. These Oceanic Anoxic Events (OAEs) represented severe disturbances to the global carbon, oxygen and nutrient cycles of the ocean. Imagine diving into water with virtually no oxygen – you’d be swimming in a liquid desert where nothing could survive.

The OAE2 was characterized by extreme atmospheric CO2 concentrations, widespread water anoxia and free hydrogen sulfide in the surface ocean. The presence of hydrogen sulfide would make the water toxic, creating conditions more suited to a science fiction horror movie than a pleasant swim.

The Heat Problem: When Warm Water Becomes Deadly

While the extreme temperatures might initially feel luxurious, they created a perfect storm for exhaustion and heat-related problems. In the cold oceanic waters, skin cooling occurs very rapidly. The next affected tissue will be muscle, particularly in the upper limbs. Research has shown that the contractile force of muscle is significantly decreased when its temperature falls below 27°C. But in reverse, the superheated Cretaceous waters would cause rapid overheating and dehydration.

Modern survival experts recommend around 12,000Kcal a day – the daily kcal requirement of five men combined for extreme endurance swimming. In the greenhouse conditions of the Cretaceous, these requirements would be even higher, making long-term survival virtually impossible.

No Escape Routes: The Geography of Doom

As a result of higher sea levels during the Late Cretaceous, marine waters inundated the continents, creating relatively shallow epicontinental seas in North America, South America, Europe, Russia, Africa, and Australia. In addition, all continents shrank somewhat as their margins flooded. At its maximum, land covered only about 18 percent of Earth’s surface, compared with approximately 28 percent today.

The geography itself worked against survival. With vast inland seas covering much of what we now consider dry land, finding a safe harbor would be nearly impossible. You wouldn’t just be swimming in an ocean – you’d be trapped in a water world where escape routes were hundreds of miles away.

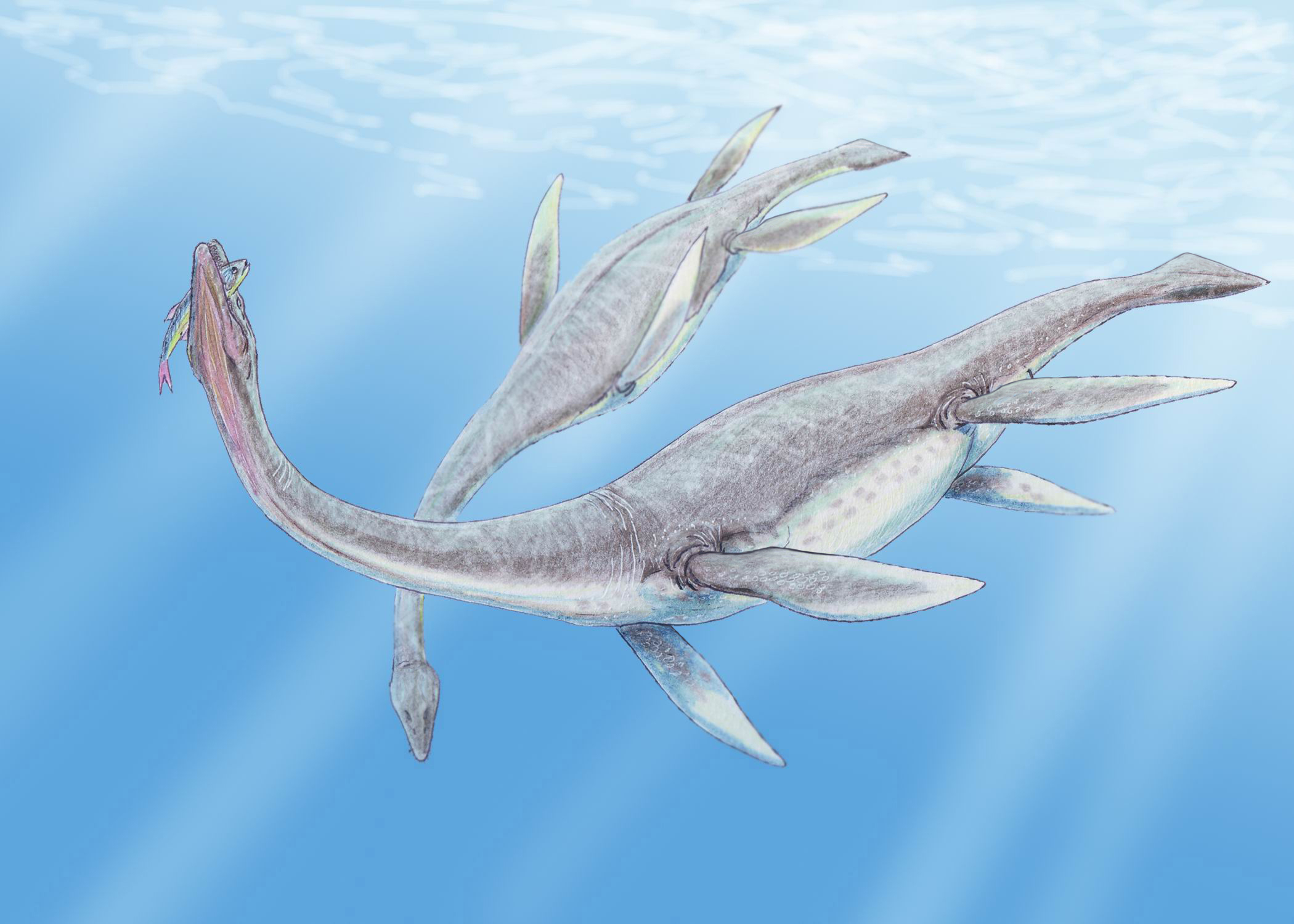

The Plesiosaur Problem: Four-Flippered Nightmares

In coordinated movements the four flippers would equally propel the plesiosaur forward, a unique swimming method in the animal kingdom. While four flippered animals like sea turtles do exist, these creatures predominantly use the front flippers for thrust and the back for steering. Most plesiosaurs were predators. Some likely grazed along the seafloor looking for soft-bodied prey while others likely aggressively ambushed their prey from below, much like the great white shark of today.

These weren’t the slow, gentle giants often portrayed in movies. They were precision hunting machines with four-wheel drive swimming capabilities. Their unique locomotion gave them maneuverability that no modern marine predator possesses, making them nearly impossible to outrun or outmaneuver.

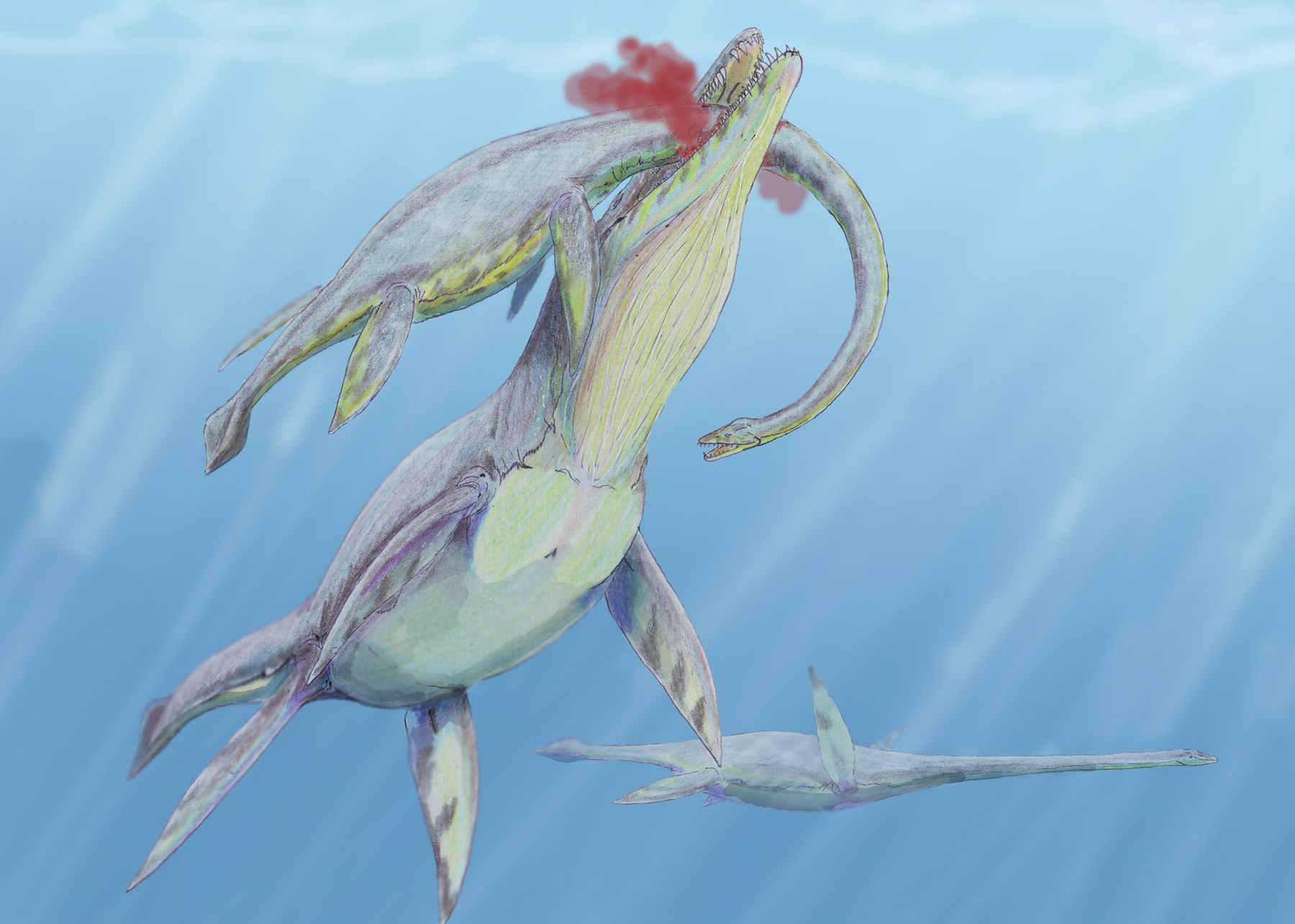

The Food Chain Collapse: When Everything Eats Everything

During the Mesozoic, the time period when dinosaurs roamed on land, many of these large creatures were the top predators in the ocean food chain and fed on fish, cephalopods, bivalves, and even one another. The Cretaceous seas operated on a completely different level of predation intensity than modern oceans. Top predators didn’t just hunt prey – they hunted each other, creating a chaotic free-for-all where size and strength meant everything.

In the ocean, there are giant mosasaurs, smaller mosasaurs, Xiphactinus, sharks, giant squid and pliosaurs. Here is a look at some of the fearsome predators in the Cretaceous sea. With this density of apex predators, the mathematical probability of avoiding all threats during even a short swim approaches zero.

Modern Survival Skills vs Cretaceous Reality

Every piece of modern ocean survival advice becomes useless in Cretaceous waters. The best way to do this is to float, not swim. But floating motionlessly would make you perfect bait for the ambush predators that dominated these seas. If you’re stuck in deep water, remember to use survival strokes to save energy. Energy conservation becomes meaningless when 40-mph fish are hunting you.

Hooper will do exactly the same – the only difference is that he will be spending at least ten hours in the ocean every day for five months. Without adequate recovery time there will be an earlier onset of fatigue with detrimental effects on performance and possibly injuries. Even world-class endurance swimmers struggle with extended ocean exposure in modern, relatively safe seas.

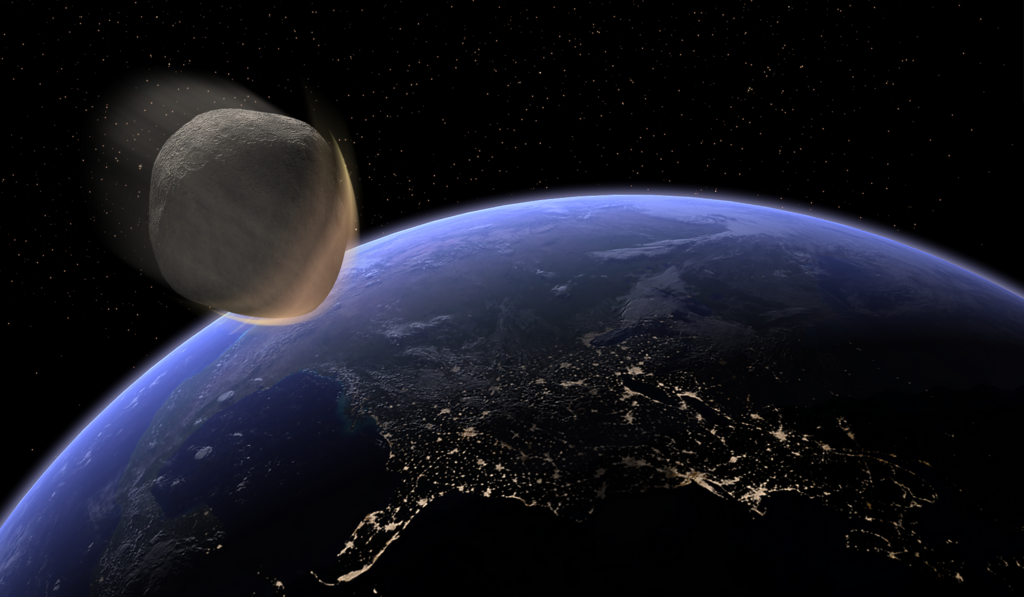

The Extinction Event Aftermath: Swimming Through Apocalypse

Overall, approximately 80 percent of animal species disappeared, making this one of the largest mass extinctions in Earth’s history. But before that final catastrophe, the Cretaceous seas were already a gauntlet of evolutionary extremes. Dinosaurs, pterosaurs, mosasaurs, and ammonoids, to name a few, were among the groups lost at this time. The Cretaceous extinction event is marked by the famous K-T boundary and asteroid impact on what is now the Yucatan peninsula.

Swimming in these waters wouldn’t just be dangerous – it would be like swimming through the peak predator period of Earth’s history, right before nature itself hit the reset button. The creatures that called these waters home were the result of millions of years of arms-race evolution, each more efficient at killing than the last.

Conclusion: The Ultimate Nightmare Pool

Could you survive swimming in the Cretaceous sea? The honest answer is that your chances would be astronomically small. Between water temperatures that could cook you like a lobster, an oxygen-depleted environment that might poison you, and the most concentrated collection of apex predators in Earth’s history, the Cretaceous oceans were essentially a death trap with perfect blue-green camouflage.

I’ve always been fascinated by the possibility of travelling back in time and simply immersing myself in the prehistoric world. But I would never ever go anywhere near the water in the Cretaceous, not unless I wanted to become some creature’s lunch. Even paleontology experts who study these creatures professionally acknowledge the terrifying reality of these ancient seas.

The next time you’re nervous about a shark sighting at your local beach, remember that we live in one of the safest oceanic periods in Earth’s history. The Cretaceous seas make our modern “dangerous” waters look like a children’s wading pool. Would you dare to take that prehistoric plunge, knowing what lurks beneath?