The National Museum of Natural History’s Fossil Halls stand as one of the Smithsonian Institution’s crown jewels, drawing millions of visitors annually to Washington, D.C. These magnificent halls house one of the world’s most comprehensive collections of prehistoric life, spanning billions of years of Earth’s history. Recently renovated after a five-year, $110 million project, the David H. Koch Hall of Fossils – Deep Time reopened in 2019, presenting not just ancient bones but a cohesive narrative about climate change, evolution, and humanity’s impact on our planet. Within these walls, visitors embark on an awe-inspiring journey through time, witnessing the spectacular diversity of life that has inhabited our planet and the dramatic environmental changes that have shaped Earth’s history.

The Historical Evolution of the Smithsonian’s Fossil Collection

The Smithsonian’s fossil collection began modestly in the mid-19th century with specimens collected during early government expeditions to the American West. These initial collections, which included dinosaur bones recovered by scientists like O.C. Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope during the infamous “Bone Wars,” formed the foundation of what would become one of the world’s premier paleontological assemblages. Throughout the 20th century, the collection expanded dramatically through field expeditions, donations, and strategic acquisitions. Today, the National Museum of Natural History houses over 40 million fossil specimens, though only a fraction—the most scientifically significant or visually impressive—are on public display. This vast collection not only showcases spectacular prehistoric creatures but also serves as an invaluable scientific resource, providing researchers with material to study evolutionary patterns, ancient ecosystems, and extinction events across geological time.

The 2019 Renovation: Reimagining Deep Time

The ambitious renovation of the fossil halls represented the largest and most complex exhibit overhaul in the museum’s history. Closing in 2014, the project aimed to completely reimagine how the Smithsonian presents paleontological science to the public. More than simply updating displays, the renovation fundamentally shifted the narrative approach, weaving together the stories of evolution, extinction, and climate change into a cohesive journey through “Deep Time”—the vast expanse of Earth’s 4.6-billion-year history. The new design intentionally connects past environmental changes with present climate challenges, helping visitors understand the relevance of ancient history to contemporary issues. The renovated hall incorporates cutting-edge museum technology, including animated projections, interactive touchscreens, and augmented reality experiences that bring fossilized creatures to life. Perhaps most significantly, the new design presents humans as just one species in Earth’s complex history while emphasizing our uniquely powerful impact on the planet’s systems.

Centerpiece Attractions: The Nation’s T. Rex and Other Iconic Specimens

Dominating the central hall stands the museum’s spectacular Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton, nicknamed the “Nation’s T. Rex.” This remarkable specimen, on loan from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, was discovered in Montana in 1988 by amateur fossil hunter Kathy Wankel. Standing over 13 feet tall and stretching 40 feet from nose to tail, this 66-million-year-old predator is one of the most complete T. rex skeletons ever found, with approximately 80-85% of its original bones intact. The dramatic pose, showing the dinosaur in the act of attacking a fallen Triceratops, creates a dynamic “prehistoric snapshot” that captivates visitors. Other iconic specimens include the museum’s towering Diplodocus, the massive skull of Triceratops, and the remarkably preserved fossil of Archaeopteryx—a creature representing the evolutionary transition between dinosaurs and birds. Each of these specimens serves as both a scientific treasure and an ambassador from Earth’s distant past, connecting visitors to creatures that vanished millions of years ago.

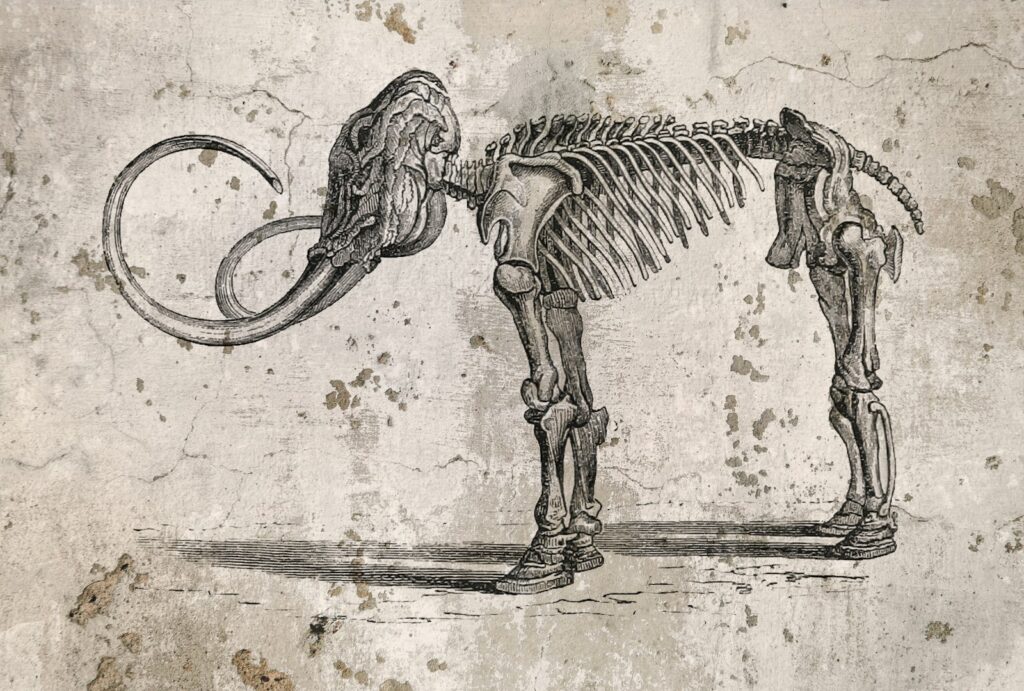

Beyond Dinosaurs: The Ancient Mammal Hall

While dinosaurs may capture the most attention, the Fossil Halls extend far beyond the “terrible lizards” to showcase the remarkable diversity of prehistoric mammals that flourished after the dinosaurs’ extinction. The Ancient Mammal Hall presents an extraordinary parade of creatures that would seem fantastical if not documented in the fossil record. Visitors can marvel at the museum’s iconic display of Megatherium, the giant ground sloth that stood 20 feet tall and weighed several tons, yet was a peaceful plant-eater related to modern sloths. Nearby stands the imposing skeleton of Mammuthus columbi, the Columbian mammoth that roamed North America during the Pleistocene epoch, standing 13 feet tall at the shoulder. The hall also features bizarre creatures like Uintatherium, a rhinoceros-sized herbivore with multiple horns and saber teeth, and the massive Brontotherium, which resembled a cross between a rhinoceros and a horse. These specimens illustrate the explosive diversification of mammals following the dinosaurs’ extinction and demonstrate evolution’s remarkable capacity to produce specialized forms adapted to every ecological niche.

Life’s First Chapters: The Hall of Ancient Life

The journey through deep time begins in the Hall of Ancient Life, where visitors encounter Earth’s earliest inhabitants. This often-overlooked section of the fossil halls presents the fascinating story of life’s origins and early evolution, covering a span of time that dwarfs the age of dinosaurs. Displays feature rare specimens of stromatolites—layered rock structures created by ancient cyanobacteria over 3.5 billion years ago—representing some of the earliest evidence of life on Earth. The Ediacaran biota display showcases impressions of soft-bodied organisms that lived over 550 million years ago, predating the evolution of hard shells and skeletons. Perhaps most impressive is the museum’s collection of Burgess Shale fossils, exquisitely preserved specimens from the Cambrian Explosion (about 508 million years ago) when complex animal life diversified rapidly. These ancient arthropods, worms, and other creatures, many with body plans unlike anything alive today, offer a window into the experimental phase of animal evolution when nature seemed to be testing different evolutionary possibilities before settling on the major body plans we recognize today.

The Oceans Through Time: Marine Paleontology Exhibits

The Smithsonian’s fossil halls provide a comprehensive view of marine life’s evolution through Earth’s history, presenting spectacular specimens from ancient oceans. Visitors can examine the diverse forms of trilobites—extinct arthropods that dominated Paleozoic seas for nearly 300 million years—with their segmented bodies and compound eyes that functioned similarly to those of modern insects. The marine reptile displays feature impressive specimens of mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and ichthyosaurs, demonstrating how several lineages of land-dwelling reptiles independently returned to marine environments during the Mesozoic era, evolving fish-like or paddle-equipped bodies for aquatic life. One of the most dramatic displays features a 50-foot-long Basilosaurus, an early whale from the Eocene epoch (about 40 million years ago) that still retained small hind limbs—compelling evidence of whales’ evolution from land-dwelling ancestors. The marine fossil collection also includes massive ammonites (extinct relatives of octopuses and squids) with intricate spiral shells, some reaching over six feet in diameter, and the razor-sharp teeth of megalodon, an enormous shark that could grow to lengths of 50 feet or more.

The Human Story: Our Species in Deep Time

The renovated fossil halls place special emphasis on humanity’s place within the continuum of life’s history, presenting human evolution as just one fascinating chapter in Earth’s ongoing story. The human evolution displays include casts of significant hominin fossils, from early species like Australopithecus afarensis (represented by the famous “Lucy” skeleton) to more recent relatives like Homo neanderthalensis. These specimens illustrate the gradual emergence of features we consider uniquely human, including bipedal locomotion, increased brain size, and tool use. Interactive displays allow visitors to compare skeletal features across hominin species and explore the genetic evidence for human evolutionary relationships. The exhibit takes care to present human evolution not as a linear progression toward an ultimate goal, but as a branching tree with multiple hominin species existing simultaneously during much of our evolutionary history. Perhaps most impactfully, the hall contextualizes human history against the backdrop of deep time—revealing how our species has existed for merely the last 300,000 years of Earth’s 4.6-billion-year history, yet has rapidly become the dominant force shaping the planet’s future.

Behind the Scenes: The Museum’s Paleontology Research

While the public displays showcase spectacular specimens, they represent only a fraction of the Smithsonian’s paleontological activities. Behind the scenes, the museum houses one of the world’s largest fossil collections, with tens of millions of specimens stored in climate-controlled conditions. These collections serve as an invaluable scientific resource, with researchers from around the world visiting to study everything from microscopic foraminifera to massive dinosaur bones. The museum’s paleontology department employs numerous scientists who conduct fieldwork worldwide, discovering new species and investigating ancient ecosystems. Recent expeditions have explored fossil-rich regions in Panama, Mongolia, and Antarctica, among others. The department maintains specialized laboratories for fossil preparation, where skilled technicians meticulously remove surrounding rock from delicate specimens using tools ranging from traditional dental picks to cutting-edge air scribes and acid baths. Advanced imaging technologies, including CT scanning and 3D modeling, allow researchers to examine internal structures of fossils without damaging specimens and to create digital models that can be shared globally, democratizing access to these scientific treasures.

Conservation in Focus: The Extinction Narrative

The renovated fossil halls deliberately frame their narrative around the concept of extinction, using ancient examples to contextualize the current biodiversity crisis. Throughout the exhibits, visitors encounter compelling stories of past extinction events, from the end-Permian “Great Dying” that eliminated approximately 90% of marine species 252 million years ago to the asteroid impact that ended the dinosaurs’ reign 66 million years ago. These exhibits explain how scientists study mass extinctions in the fossil record, identifying patterns that help distinguish gradual environmental changes from catastrophic events. Interactive displays allow visitors to explore the varying causes of past extinctions—including volcanic activity, climate change, and extraterrestrial impacts—and their differing impacts on terrestrial and marine ecosystems. Most significantly, the hall draws explicit connections between these prehistoric events and the current human-driven extinction crisis, noting that current extinction rates may be 100 to 1,000 times higher than background rates. This framing helps visitors understand that extinction is a natural process that has shaped life throughout Earth’s history, but the current accelerated pace presents an unprecedented challenge to biodiversity and ultimately to human welfare.

Interactive Learning: Engaging the Public with Paleontology

The fossil halls employ numerous innovative approaches to engage visitors of all ages in active learning about Earth’s prehistoric past. Throughout the exhibits, interactive touchscreens invite visitors to explore topics in greater depth, from the mechanics of dinosaur movement to the techniques scientists use to determine ancient climates. The popular FossiLab, visible through large windows, allows visitors to observe museum scientists and volunteers preparing fossils, providing a real-time glimpse into paleontological work. Digital installations create immersive experiences, including time-lapse animations showing continental drift over millions of years and reconstructions of ancient ecosystems coming to life on large screens. For younger visitors, the Fossil Basecamp area provides hands-on learning stations where children can touch real fossils, compare modern and ancient animals, and try their hand at fossil identification puzzles. The museum also offers specialized guided tours, fossil identification workshops, and regular “Scientist Is In” programs where visitors can meet paleontologists and ask questions about their research. These diverse engagement strategies help transform what could be a passive viewing experience into an active exploration of Earth’s history.

Artistic Reconstructions: Bringing Prehistoric Life to Visual Reality

Throughout the fossil halls, scientific accuracy meets artistic imagination in spectacular reconstructions that bring ancient creatures and environments to life. Large-scale murals, created by some of the world’s leading paleoartists, depict prehistoric landscapes populated with scientifically accurate renderings of extinct animals and plants. These scenes are carefully created in collaboration with paleontologists to reflect the latest scientific understanding of how these creatures looked, moved, and behaved. Three-dimensional models showcase extinct creatures with realistic skin, feathers, and coloration based on fossil evidence, helping visitors visualize the living animals behind the fossilized bones. Particularly impressive are the life-sized models of Triceratops and Tyrannosaurus rex that include details like muscle structure, skin texture, and even subtle coloration patterns based on evidence from exceptionally preserved fossils and studies of modern relatives. Digital animations take reconstruction a step further, showing extinct animals in motion based on biomechanical studies of their skeletons. These artistic elements serve a crucial scientific communication purpose, helping bridge the gap between technical paleontological knowledge and public understanding of ancient life.

Special Exhibits and Rotating Displays

Beyond the permanent fossil halls, the Smithsonian regularly features special paleontological exhibits that explore specific aspects of prehistoric life in greater depth. These temporary installations allow the museum to highlight new discoveries, commemorate significant anniversaries in paleontological history, or explore specialized topics that complement the main halls. Recent special exhibits have included “The Last American Dinosaurs,” which focused on the ecosystem just before the end-Cretaceous extinction, and “Titanoboa: Monster Snake,” featuring the remains of a 48-foot snake that lived 60 million years ago. The museum also maintains several rotating display cases within the fossil halls themselves, where newly acquired specimens or fossils of special scientific interest can be showcased for limited periods. These rotating displays often feature recent discoveries from Smithsonian expeditions, allowing visitors to see fossils that may have been in the ground just months earlier. Special exhibits frequently incorporate experimental display techniques or interactive elements that might later be incorporated into permanent exhibitions, serving as testing grounds for new approaches to public engagement with paleontological science.

Planning Your Visit: Practical Information and Tips

Visitors planning to explore the Smithsonian’s fossil halls should allocate at least two hours to fully appreciate the extensive exhibits, though enthusiasts could easily spend a full day examining displays in detail. Like all Smithsonian museums in Washington, D.C., admission to the National Museum of Natural History is free, making it an exceptional educational value. The museum is typically open daily from 10:00 AM to 5:30 PM, though hours may vary seasonally and on holidays. Weekday mornings, especially Tuesday through Thursday, typically offer the least crowded experience, while weekends and summer months bring substantially larger crowds. For those seeking a more personalized experience, the museum offers several guided tour options, including general overview tours and specialized paleontology-focused tours led by knowledgeable docents. The free Smithsonian mobile app provides helpful navigation assistance, background information on key specimens, and suggested thematic routes through the exhibits. Visitors with special interests might consider contacting the museum in advance, as behind-the-scenes tours of research collections are occasionally available for serious enthusiasts or educational groups with specific research interests.

The Future of the Fossil Halls: Ongoing Research and Updates

The Smithsonian’s commitment to paleontological science ensures that the fossil halls remain dynamic spaces that evolve as scientific understanding advances. Museum staff regularly update displays to reflect new discoveries and changing interpretations, from minor label revisions to more substantial exhibit modifications. Current research projects that may influence future displays include studies of dinosaur coloration using fossilized melanosomes, investigations of ancient DNA from recently extinct species, and analyses of fossil plants to reconstruct prehistoric climate patterns. The museum has embraced digital technology to enhance the visitor experience, with plans to expand augmented reality offerings that would allow visitors to use smartphones or tablets to see fossils transformed into living creatures. Looking further ahead, museum leadership has expressed interest in creating more connections between the fossil halls and other museum sections, particularly the human origins and ocean halls, to present a more integrated view of Earth’s biological and geological systems. As climate change continues to reshape our planet, the fossil halls will likely evolve to place even greater emphasis on using Earth’s past to inform our understanding of possible futures, solidifying their role not just as showcases of prehistoric wonders but as vital educational resources for a planet in transition.

The Fossil Halls of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History offer far more than an impressive collection of ancient bones. They provide a comprehensive narrative of life’s evolution, extinction’s role in shaping biodiversity, and humanity’s place within Earth’s long history. By connecting past environmental changes with current challenges, these halls help visitors contextualize contemporary issues like