When we think about the Jurassic Period, our minds naturally drift to towering sauropods and fearsome predators roaming the land. But while dinosaurs dominated the terrestrial realm, the ancient oceans were home to equally spectacular creatures that ruled the seas with remarkable diversity and complexity. The marine ecosystems of the Jurassic were teeming with life forms that were every bit as fascinating and diverse as their land-dwelling contemporaries.

The Jurassic Ocean: A World Transformed

The Jurassic Period, spanning from about 201 to 145 million years ago, witnessed dramatic changes in Earth’s geography and climate that profoundly shaped marine life. Most of what later became Britain was under the sea, apart from Scotland, East Anglia and a series of small islands in the southwest, with new oceans flooding the spaces created by continental breakup and mountains rising on the seafloor, pushing sea levels higher onto the continents.

All this water gave the previously hot and dry climate a humid and subtropical feel, while analyses of oxygen isotopes in marine fossils suggest that Jurassic global temperatures were generally quite warm, with surface waters in the low latitudes about 20°C and deep waters about 17°C. This warm, stable climate created ideal conditions for marine life to flourish in ways that would seem alien to modern observers.

Ammonites: The Spiral Shells That Ruled the Seas

Ammonites ranged in size from just a few centimetres to as large as a bicycle wheel, and they were predators, stalking and feeding on crustaceans and other sea creatures, using long arms that would extend from their hard shells. These remarkable cephalopods weren’t just passive drifters but active hunters that played crucial roles in Jurassic marine ecosystems.

Over 10,000 species of ammonite – possibly even over 20,000 – have been discovered, and they were quite diverse and evolved rapidly, so if you sample stratigraphically through rocks, you can actually see the evolution and the changes through them. Larger sizes were more common from the Late Jurassic onwards, and though it would largely have depended on their size, ammonites would likely have eaten similar things to today’s cephalopods, such as crustaceans, bivalves and fish, with smaller species probably eating plankton.

Belemnites: The Bullet-Shaped Hunters

Belemnites were marine animals belonging to the phylum Mollusca and the class Cephalopoda, living during the periods of Earth history known as the Jurassic and Cretaceous, with the Jurassic Period beginning about 201 million years ago and the Cretaceous Period ending about 66 million years ago. Unlike their modern squid relatives, these ancient cephalopods possessed internal skeletons that have left behind distinctive bullet-shaped fossils.

Belemnites, in life, are thought to have had 10 hooked arms and a pair of fins on the guard, with chitinous hooks usually no bigger than 5 mm, though a belemnite could have had between 100 and 800 hooks in total, using them to stab and hold onto prey. They were an important food source for many Mesozoic marine creatures, both the adults and the planktonic juveniles, and they likely played an important role in restructuring marine ecosystems after the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event.

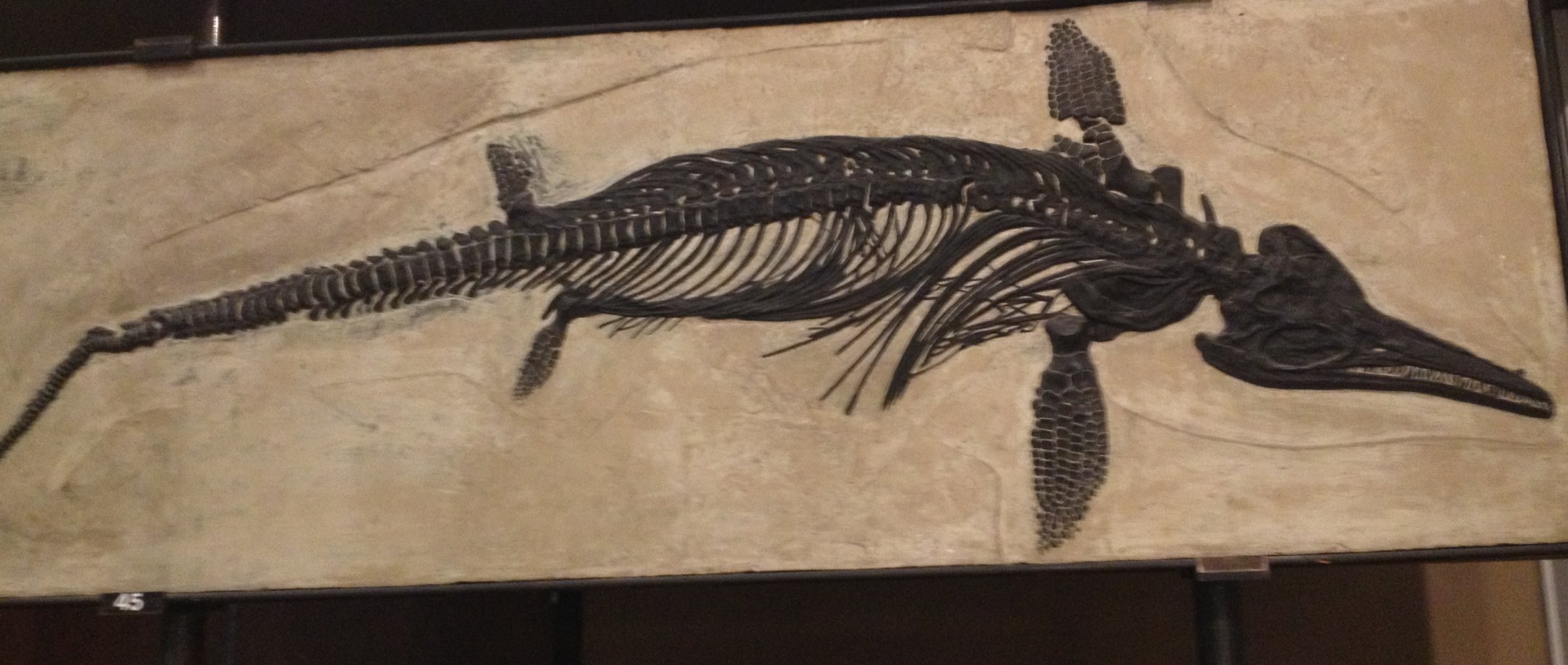

Ichthyosaurs: The Dolphin-Like Reptiles

Large marine reptiles lived in the ocean alongside ammonites, including ichthyosaurs and long-necked plesiosaurs, with ichthyosaurs being at their most successful during the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic, but had been overtaken by the plesiosaurs as dominant marine animals by the Late Jurassic. These remarkable reptiles had evolved from land-dwelling ancestors into perfectly adapted ocean predators.

Their limbs had been fully transformed into flippers, which sometimes contained a very large number of digits and phalanges, at least some species possessed a dorsal fin, their heads were pointed, and the jaws often were equipped with conical teeth to catch smaller prey, with eyes that were very large, for deep diving. In 1994, Judy Massare concluded that ichthyosaurs had been the fastest marine reptiles, with their length/depth ratio between three and five being the optimal number to minimize water resistance, their smooth skin and streamlined bodies preventing excessive turbulence, and their hydrodynamic efficiency approaching that of dolphins at about 0.8.

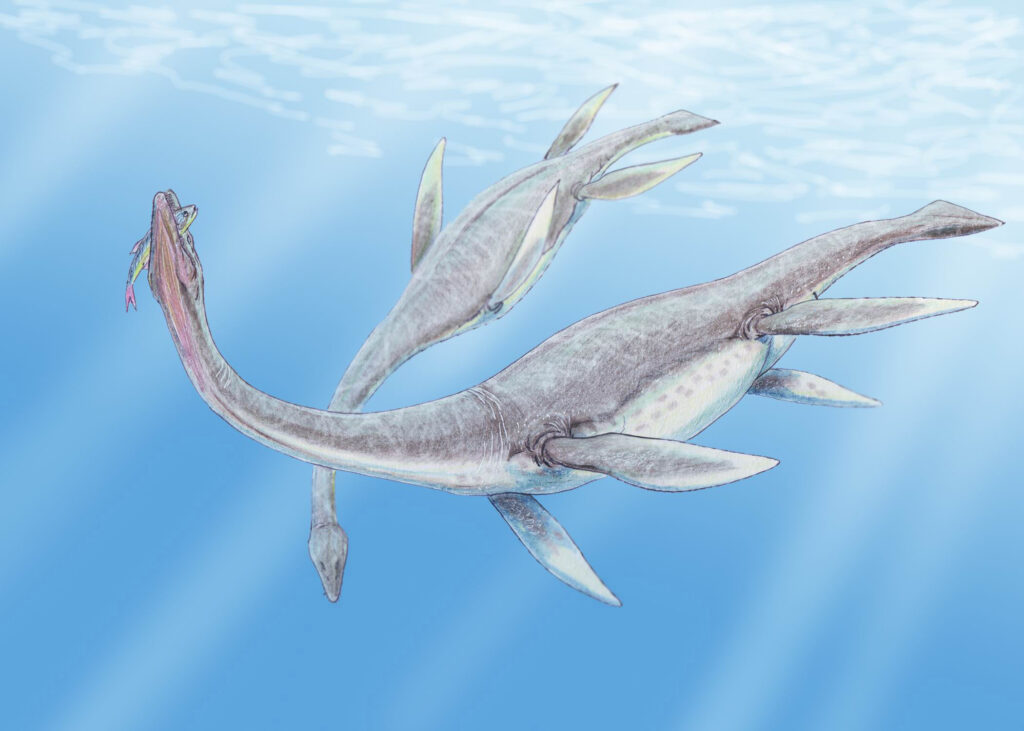

Plesiosaurs: The Long-Necked Sea Serpents

Whereas ichthyosaurs propelled themselves through the water with a large tail fin, the plesiosaurs swam using strokes of their four powerful flippers, and over the course of the Jurassic Period, the plesiosaurs split into two main branches: those with long necks and small heads, and those with short necks and large heads. The diversity of plesiosaur body plans reflected their adaptation to different ecological niches in Jurassic seas.

Plesiosaurs retained their ancestral two pairs of limbs, which had evolved into large flippers, and the flipper arrangement is unusual for aquatic animals in that probably all four limbs were used to propel the animal through the water by up-and-down movements, with the tail most likely only used for helping in directional control, contrasting to the ichthyosaurs and the later mosasaurs, in which the tail provided the main propulsion.

Pliosaurs: The Apex Predators

Liopleurodon was a member of a group of short-necked plesiosaurs known as pliosaurs, and this fearsome Jurassic animal was likely to have been an apex predator, feeding on fish, cephalopods, and a variety of marine reptiles, and it may have even been able to catch unwary dinosaurs who had strayed too close to the water’s edge. These massive predators represented the ultimate evolution of marine reptile hunting prowess.

Liopleurodon was once thought to have grown to lengths of up to 25 meters but recent estimations have brought its maximum length down to around 6.4 meters making it slightly smaller than today’s killer whales, though in general, plesiosaurians varied in adult length from between 1.5 meters to about 15 meters, with the group containing some of the largest marine apex predators in the fossil record, roughly equalling the longest ichthyosaurs, mosasaurids, sharks and toothed whales in size.

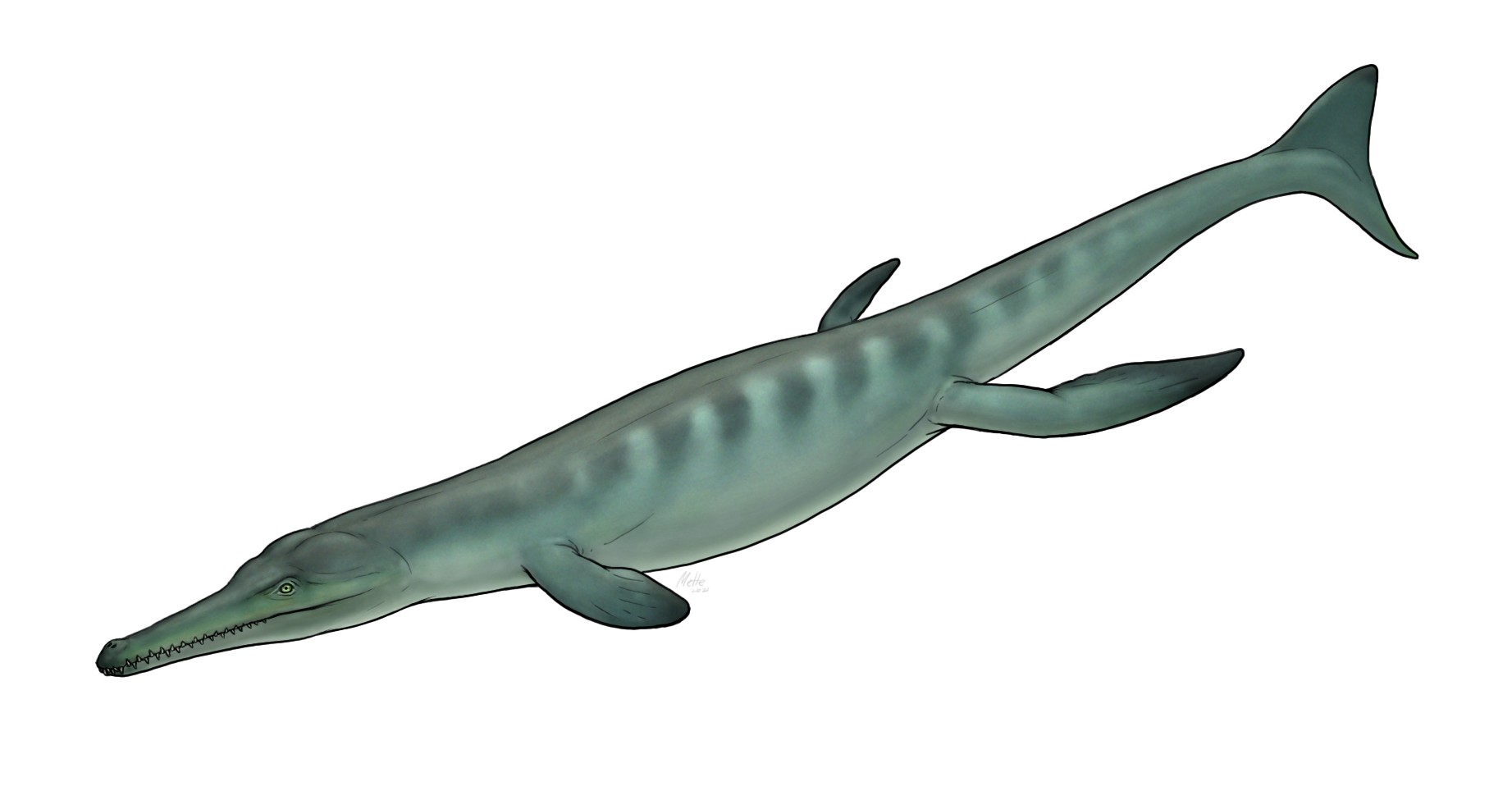

Thalattosuchians: The Ocean-Going Crocodiles

The Thalattosuchia, a clade of predominantly marine crocodylomorphs, first appeared during the Early Jurassic and became a prominent part of marine ecosystems, with the Metriorhynchidae within Thalattosuchia becoming highly adapted for life in the open ocean, including the transformation of limbs into flippers, the development of a tail fluke, and smooth, scaleless skin.

During the Jurassic Period, however, the early crocodiles were restricted to an aquatic lifestyle, and were found in both freshwater and marine habitats, with several early crocodiles taking to the oceans in order to survive as the dinosaurs became the dominant meat-eaters on land. These adaptations showed how flexible reptilian body plans could become when faced with new ecological opportunities in marine environments.

Fish of the Jurassic Seas

Fish had been swimming in the world’s oceans hundreds of millions of years prior to the start of the Jurassic Period, and during the Jurassic Period fish continued to evolve, and, along with the reptiles, were the primary marine vertebrates, while modern sharks and rays first appeared and diversified during the period, with the first known crown-group teleost fish appearing near the end of the period.

Leedsichthys – possibly the largest fish that ever lived – reached an estimated length of around 16.5 meters according to recent studies. This gentle giant likely filter-fed on plankton, much like modern whale sharks, demonstrating that not all large marine predators of the Jurassic relied on active hunting strategies.

Marine Invertebrates: Building the Foundation

At the top of the food chain were the long-necked and paddle-finned plesiosaurs, giant marine crocodiles, sharks, and rays, but coral reefs grew in the warm waters, and sponges, snails, and mollusks flourished. In the oceans, life on the seafloor became more complex and modern, with an abundance of mollusks and coral reef builders by Middle Jurassic time.

Microscopic, free-floating plankton proliferated and may have turned parts of the ocean red, with more than 60 percent of the world’s oil beginning as microscopic marine plankton in the Jurassic and Cretaceous. These tiny organisms formed the base of complex food webs that supported the spectacular diversity of larger marine life.

Evolution and Extinction in Jurassic Seas

The Triassic-Jurassic boundary is marked by one of the five largest mass extinctions on Earth, with about half of the marine invertebrate genera going extinct at this time, and at least two other Jurassic intervals show heightened faunal turnover affecting mainly marine invertebrates – one in Early Jurassic time and another at the end of the period.

During the Early Jurassic, animals and plants living both on land and in the seas recovered from one of the largest mass extinctions in Earth history, with many groups of vertebrate and invertebrate organisms important in the modern world making their first appearance during the Jurassic. The recovery and diversification following mass extinction events demonstrates the remarkable resilience of marine ecosystems.

Conclusion

The marine life of the Jurassic Period reveals a world far more complex and diverse than popular imagination might suggest. While dinosaurs captured the spotlight on land, the oceans teemed with an extraordinary array of predators, filter feeders, and countless smaller organisms that together created some of the most productive marine ecosystems in Earth’s history. From the spiral shells of ammonites to the streamlined bodies of ichthyosaurs, from the powerful jaws of pliosaurs to the delicate structures of microscopic plankton, Jurassic seas were home to evolutionary experiments that would influence marine life for millions of years to come.

Understanding these ancient marine ecosystems helps us appreciate not just the diversity of life that once existed, but also the dynamic nature of evolution itself. The Jurassic oceans were laboratories of adaptation, where creatures pushed the boundaries of what was possible in aquatic environments. What legacy do you think these ancient marine pioneers left for modern ocean life?