When we think of dinosaurs, our minds often leap to the towering giants that ruled later ages—but in the Triassic, it was the little guys who had the upper hand. Small, agile dinosaurs darted through the shadows of larger reptiles, using speed, sharp senses, and clever adaptations to survive. While bulkier rivals relied on brute force, these nimble survivors exploited opportunities, from hunting insects to sneaking through tough environments. Fossil evidence shows that their adaptability gave them a crucial edge when ecosystems shifted. In the end, it wasn’t size that mattered most—it was strategy, and the small dinosaurs played the game brilliantly.

The Great Dying’s Aftermath: Setting the Stage for Dinosaur Ingenuity

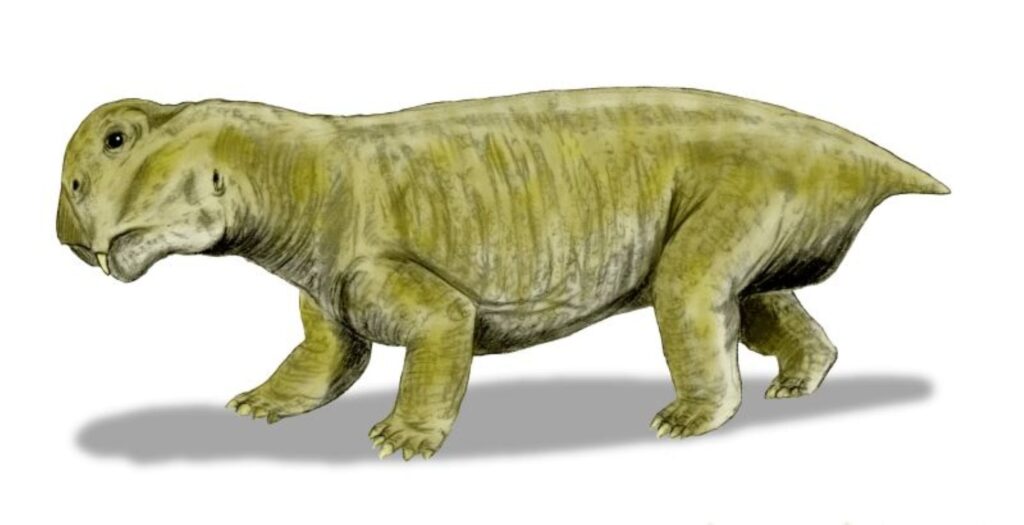

The Triassic Period began after the Permian–Triassic extinction event devastated life on Earth roughly 252 million years ago, marking one of the most significant events in planetary history. Picture this: Earth had just survived what scientists call “the Great Dying,” and suddenly the planet was like a massive empty theater with most of the previous performers gone. The early Triassic was dominated by mammal-like reptiles such as Lystrosaurus, which accounted for as many as 95% of the total individuals in some fossil beds.

This wasn’t exactly the world you’d expect dinosaurs to conquer. True archosaurs appeared in the early Triassic, splitting into two branches: Avemetatarsalia (the ancestors to birds) and Pseudosuchia (the ancestors to crocodilians), with avemetatarsalians being a minor component of their ecosystems. The stage was set for an unlikely underdog story that would reshape life on Earth for the next 165 million years.

When Size Wasn’t Everything: The Rise of Bipedal Speed Demons

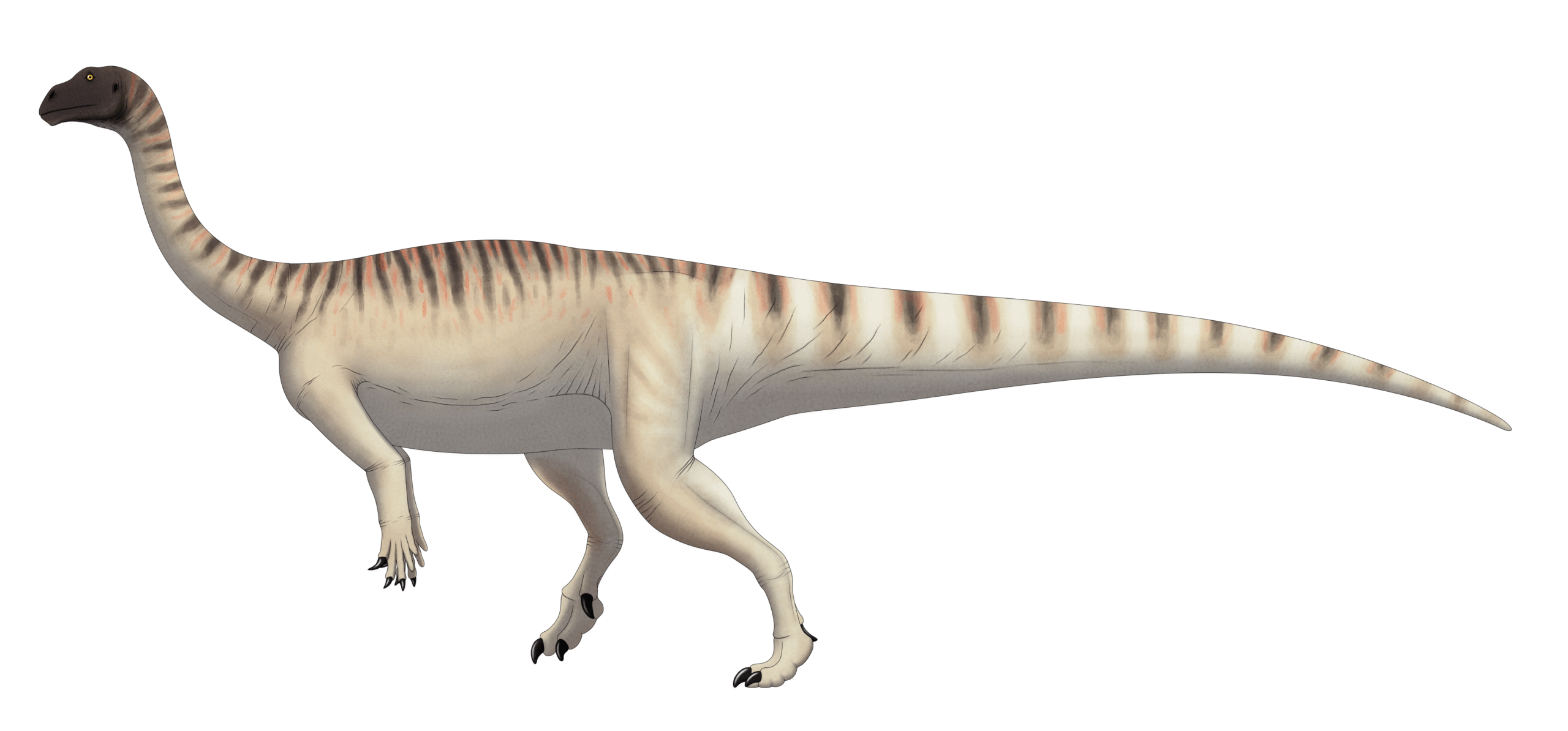

Around 240 million years ago, the first dinosaurs appeared in the fossil record as small, bipedal creatures that would have darted across the variable landscape. Think of them as the motorcycle couriers of the ancient world – small, nimble, and incredibly efficient at getting around quickly. The early dinosaurs were bipedal, swift-moving, and relatively small compared with later Mesozoic forms.

What made these early dinosaurs special wasn’t their intimidating presence – most were only the size of chickens or small dogs. Most Triassic dinosaurs were small predators and only a few were common, such as Coelophysis, which was 1 to 2 metres long. Their secret weapon was something far more valuable in the dangerous world of the Triassic: speed and agility that could outmaneuver the lumbering giants that ruled the land.

Engineering Marvels: The Hollow Bone Revolution

Coelophysis means ‘hollow form’ and comes from the hollow limb bones, a feature shared by many other dinosaurs that gave them a lightly-built body, helping them be swift, agile hunters. This wasn’t just a random evolutionary quirk – it was like switching from heavy steel armor to lightweight carbon fiber in modern racing. With hollow leg bones, they could reach speeds of up to 25mph thanks to their light frame.

Imagine trying to chase down prey or escape predators when your bones are solid and heavy versus having a skeleton that’s essentially been engineered for speed. These hollow bones didn’t make the dinosaurs weaker – they made them faster, more agile, and capable of quick bursts of energy when it mattered most. It was like nature had given them a performance upgrade that their competitors simply didn’t have.

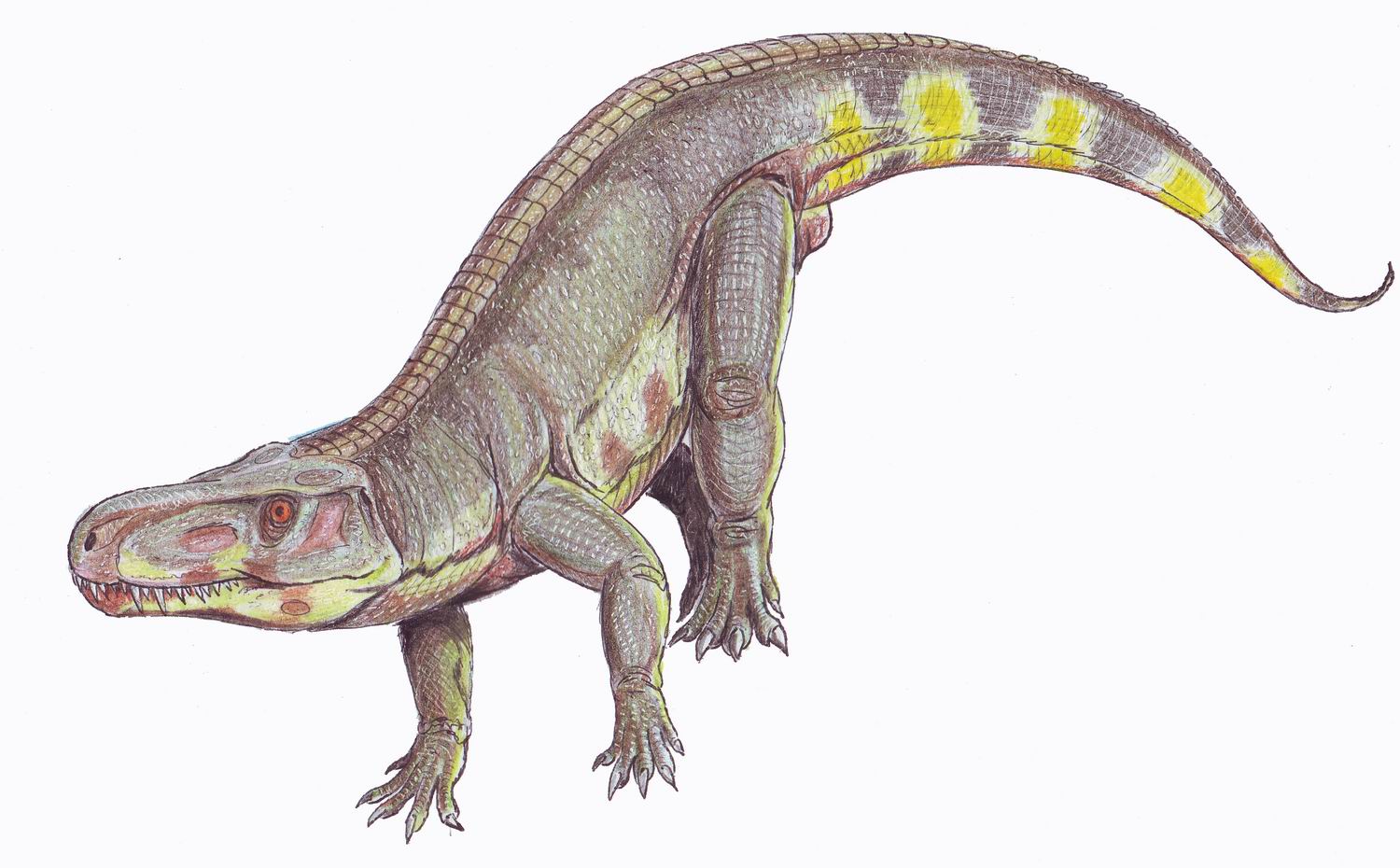

David vs Goliath: Facing the Triassic Titans

Rauisuchians were the keystone predators of most Triassic terrestrial ecosystems, with over 25 species found, including giant quadrupedal hunters, sleek bipedal omnivores, and lumbering beasts with deep sails on their backs. Picture a world where massive crocodile-like predators ruled the land, some reaching lengths of over 30 feet. In the Late Triassic Period dinosaurs were not at the top of the food chain, with early large reptiles called phytosaurs and rauisuchids dominating instead.

These weren’t just big – they were absolutely massive compared to the early dinosaurs. But here’s where the story gets interesting: being huge in the Triassic wasn’t automatically a winning strategy. Emerging during the Late Triassic period, when dinosaurs had yet to ascend to the top of the food chain, Coelophysis probably relied on its speed and agility to evade larger predators and capture prey. The small dinosaurs had learned to play a completely different game.

Speed as Survival: The Art of Evasive Maneuvering

Early meat-eating dinosaurs like Coelophysis relied on their speed and agility to catch a variety of animals like insects and small reptiles. But speed wasn’t just about catching dinner – it was about staying off someone else’s menu. Dr Tom Stubbs highlighted how dinosaurs originated as agile, bipedal insect-eaters, with their agility and varied leg posture enabling their ancestors to swiftly navigate environments while evading larger predators.

Coelophysis, a nimble predator, thrived in the Late Triassic period as a slender dinosaur built for quick pursuits through forested environments, with sharp instincts combined with agility making it a formidable hunter whose lightweight structure allowed quick turns and sudden movements essential for survival in a competitive ecosystem. Think of it like being a motorcyclist in heavy traffic – you might be smaller, but you can slip through gaps and change direction in ways that larger vehicles simply can’t match.

The Multi-Tool Advantage: Dietary Flexibility in Harsh Times

Eoraptor’s teeth were varied in shape, suggesting a diverse diet and hinting at an omnivorous nature, with this dietary flexibility being a significant advantage in the changing Triassic landscape and contributing to its agility and speed. While the giant predators were locked into specific hunting strategies and prey types, the small dinosaurs were like Swiss Army knives – adaptable and ready for whatever opportunities came their way.

Eucoelophysis may have hunted small vertebrates such as early mammals and reptiles, though its diet was likely primarily comprised of insects, with its sharp teeth and agile body making it an effective predator capable of quick bursts of speed to catch prey while moving on two legs with agility to navigate various terrains. When times got tough, these flexible feeders could switch between hunting insects, scavenging, or even munching on plants – options that massive specialized predators simply didn’t have.

Pack Dynamics: Strength Through Numbers and Coordination

Maiasaura, the “good mother lizard,” demonstrates dominance through abundance and successful social strategies, living in large herds with communal nesting sites indicating complex social structures and parental care, with fossil evidence showing parents likely guarded eggs and cared for young after hatching. But it wasn’t just the herbivores that figured out the power of group living. Many small theropods learned that what they lacked in individual size, they could make up for in numbers and coordination.

Despite their sociable nature, Coelophysis are not inclined towards pack hunting, although they prefer to live in groups, able to flourish within their enclosure with ample open spaces and the company of their own pack. Even when they weren’t actively hunting together, the safety and awareness that came from group living gave these small dinosaurs a significant advantage over solitary giants who had to rely entirely on their own senses and strength.

Built for Endurance: The Metabolic Edge

The most notable feature of Eodromaeus was its adaptation for speed and agility, as this slender, light dinosaur had powerful hind limbs to help it reach high speeds while chasing prey or evading predators. But there’s more to this story than just quick sprints. Cold periods induced by volcanic ejecta clouding the atmosphere might have favoured endothermic animals, with dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and mammals being more capable at enduring these conditions than large pseudosuchians due to insulation.

The small dinosaurs had developed something their larger competitors lacked – the ability to maintain their energy levels and body temperature more efficiently. In the Late Triassic, it was one of the most cursorial dinosaurs–dinosaurs adapted to running. While the massive cold-blooded archosaurs would become sluggish in cooler temperatures, these smaller dinosaurs could keep moving, hunting, and staying alert. It was like having a fuel-efficient engine versus a gas-guzzling monster – when resources became scarce, efficiency mattered more than raw power.

Niche Specialization: Finding Opportunities Others Missed

Understanding “dominance” for extinct creatures involves evaluating multiple ecological and evolutionary metrics, with one interpretation centering on physical attributes while another considers species dominant if they occupy the top of the food chain as apex predators, and abundance and population size also indicating dominance. The small dinosaurs understood something crucial: you don’t need to be the biggest predator to be successful – you just need to find your niche and excel at it.

Early dinosaurs like Coelophysis exemplify dominance through lineage longevity and early widespread success, as this agile, medium-sized predator thrived during the Late Triassic period over 200 million years ago, with its lightweight build allowing for speed, reaching 25 miles per hour, and its widespread fossil record across Pangaea indicating early and lasting success across diverse environments. They carved out ecological niches that the giants couldn’t access – hunting in dense forests, pursuing small prey through tight spaces, and exploiting food sources that were beneath the notice of massive predators.

The Ultimate Extinction Lottery: Surviving the End-Triassic Crisis

The Triassic–Jurassic extinction event marks the boundary between the Triassic and Jurassic periods 201.3 million years ago, representing one of five major extinction events during the Phanerozoic. When the end-Triassic extinction hit, it was like a cosmic game of chance – but the small dinosaurs had unknowingly bought themselves better odds. The End-Triassic extinction resulted in the demise of some 76 percent of all marine and terrestrial species and about 20 percent of all taxonomic families, and was likely the key moment allowing dinosaurs to become Earth’s dominant land animals.

Dinosaurs survived the mass extinction at the end of the Triassic, but that doesn’t mean they were superior to the animals that went extinct or somehow “deserved” to succeed. What saved them wasn’t superiority – it was adaptability, small size, and the ability to survive on limited resources when the world turned hostile. Several important clades of crurotarsans disappeared, as did most of the large labyrinthodont amphibians, groups of small reptiles, and most synapsids, while some early, primitive dinosaurs also became extinct, but more adaptive ones survived to evolve into the Jurassic.

From Underdogs to Overlords: The Triassic Legacy

In the TJME’s aftermath, dinosaurs experienced a major radiation, filling some of the niches vacated by the victims of the extinction. The story of small Triassic dinosaurs isn’t just about survival – it’s about how sometimes the meek really do inherit the Earth. At the end of the Triassic, Pseudosuchians were actually more diverse than dinosaurs, but extinction events happened that led to more extinction in major groups of Pseudosuchians, opening up niches that dinosaurs were able to move into and diversify, making the rest of the Mesozoic the age of dinosaurs.

Their diversity of posture and focus on fast running meant that dinosaurs could diversify when they had the chance, and after the end-Triassic mass extinction, we get truly huge dinosaurs, over ten meters long, with the diversity of their posture and gait making them immensely adaptable, ensuring strong success on Earth for so long. The small, speedy, adaptable dinosaurs of the Triassic had proven that in the game of evolution, it’s not always the biggest player who wins – sometimes it’s the smartest, fastest, and most flexible one who gets to write the next chapter of Earth’s story.

Conclusion

The story of how small dinosaurs outsmarted their larger rivals in the Triassic reads like the ultimate underdog tale, but with a twist that changed the course of life on Earth forever. These pint-sized pioneers didn’t win through brute force or intimidation – they succeeded through speed, adaptability, and sheer evolutionary cleverness. Their hollow bones, bipedal locomotion, dietary flexibility, and efficient metabolisms weren’t just random traits – they were survival tools perfectly suited for a world in constant flux.

When the Triassic world came crashing down in massive extinction events, it wasn’t the mighty rauisuchians or the dominant pseudosuchians who inherited the Earth. It was these small, quick-thinking dinosaurs who had spent millions of years perfecting the art of survival through intelligence rather than size. They proved that in nature’s grand casino, sometimes the best strategy isn’t to bet big – it’s to stay nimble, keep your options open, and be ready to seize opportunities when the giants fall. What would you have guessed – that the future rulers of Earth were hiding in plain sight, just waiting for their moment to shine?